table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

Different Country

Shaun Carter speaks to this year’s Gold Medal winner Peter Stutchbury about understanding country and his wool shed designs.

Shaun Carter (SC): Your philosophy of architecture seems to fundamentally relate to site and place. You, more than most, seek a fundamental understanding of country. Deepwater Woolshed might be considered a revolutionary building in regards to the woolshed type; but I suspect you really just thought about it from that position that you approach all your architecture. Would that be a fair thing to say?

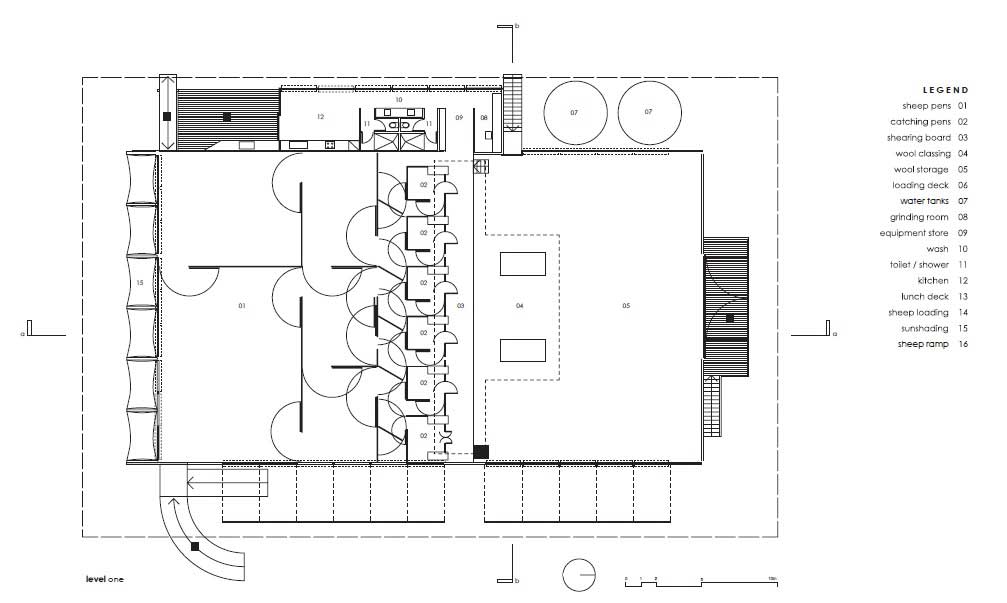

Peter Stutchbury (PS): Deepwater Woolshed, in many ways, was a key project for our team. It helped validate our process along with revealing the unpretentious aesthetic of accurate integrated decisions. I was fortunate to work with Sacha Zehnder on this project.

We spent three days at the site, and it was good that we did because the prevailing breezes that come down from the north-east turn on a small mountain called Mount Albert near the site then coming in from the west which is very unexpected. So we had to design the wool shed according to some very precise site conditions and then we just basically looked at the patterns of the site. Growing up on the family farm I had an understanding of the functional nature of a shearing shed.

So we systematically went through the building and made functional decisions about its workings. And in a funny way it got to the point where the functional decisions were providing the aesthetic qualities, there was a wonderful symphony between the two. It was never a competition of thoughts and to me it was quite a revelation – a step up in design, not a step down. It was the opportunity to design a building, the way one truly understands how to design a building, which no one has ever really assessed. The result was a great lesson to me because in some sort of innate way it made sense in the landscape, even though it was a functional building. The big eaves were about shade; the sheep actually baulk when you get to the contrast of light at the face of the shed which to date had not been managed properly. These big five metre eaves were beautiful in the landscape but off the ground at the precise height for loading wool bales onto the back of the truck without mechanised means, it also meant it hovered above the landscape and site, it changed scale across the broadness of the land dependent upon a reference – when a person was there it looked big and when a truck came along it was small.

We did the auditorium at Newcastle where we trapped the heat emitted from people and used it to temper the heat from the ground, so that it rose from 21 degrees geothermal up to 24 degrees output. So like that we caught the heat from the sheep, captured within a lowered ceiling, we took that heat across and blew it on the shearers in winter. It was all these very systematic, programmatic and functional things that we did, accurately and cheaply actually, that worked! As a consequence, we’re doing further woolsheds developing the systems.

SC: So you’re designing woolsheds for people and sheep, rather than just getting the wool off them. It seems a more empathetic way of designing. You mentioned that it taught you a few lessons as you went along. Could you tell us about those lessons, and could perhaps some the functional or programmatic elements that you needed to solve inform an architectural language. Would that be accurate?

PS: Exactly right. What I learnt (without trying to learn it), what I discovered really, was that if you’re forthright enough to make clean, clear decisions, your architectural skill will negotiate those into architecture. You don’t need to make an architectural decision first, you can make it as part of the process of making or designing the building. So if the early decisions are clear, strong and functional decisions the later decisions seemed to belong in harmony; rather than sing out of tune.

I think as you move into a more public building or private residence the ambitions of those decisions is the understanding of scale and light. That’s the ambition. That functional strategy is really interesting. For instance, we put the shearers’ rest area on the north eastern corner. So it had the morning sun, but it didn’t have the afternoon sun because it can be bloody hot.

One of the shearers came up to me and said, “Do you have any idea how beautiful it is to use this? In the morning we get the sun and in the afternoon we get the shade,” he said, “It’s perfect”. And we put the water tanks on the south east corner where there’s the most shade and you make those decisions. And they seem obvious, but it’s the way you inform a building and I think the building benefits from that, that’s the great lesson. In terms of making architecture there is another special thing, which I think is mood – which is the one thing we all struggle to find.

SC: I guess in some ways that is like this country. What I love about Aboriginal culture is not only the deep understanding of the land and their place in it – taught to them by the harsh but beautiful Australian country. These are fundamental lessons, if you unlearn them then no computer or device is going to get you there, you are going to have to relearn them all over again.

PS: Yes, what aboriginal people believe is that they are part of a refinement, so that each generation is refining the last one’s way of life. Whereas we as a culture are concentrating on

upwards. That each one of us is better than the last. Which is not how the Aboriginals see it, they don’t see it as better or worse, but as a refinement, getting clearer and clearer. It is something Western culture doesn’t seem to understand, we miss the fundamental process of respect.

SC: One’s infinite and one is finite … You are looking to the fundamental concepts rather than style?

PS: That is what makes sense to me … I don’t get style. I can’t manage or follow that method. Country, I’m starting to appreciate that language: “It is what it is.” Once I started to understand that construct, I learnt how to see it better. I met an aboriginal elder and he revealed this insight in a simple way. And it’s no big deal, it’s just respecting the land and respecting people, which I think is fundamental. And I think we make better urban, suburban and rural environments when we do that.

Putting people up in tall towers and expecting them to have an integrated urban life is not how I think it should happen. Take Paris, Paris urban life is maximum six stories, street contact is maintained.

SC: It is a very civilised way of living in Paris.

PS: Yes, very civilised. Copenhagen: very civilised. St Petersburg: very civilised. They all have a scale which is visually manageable. So my regional work, the inland work, the desert work they’re all connected, but they’re all different because the places are all emotionally different … I talk about place, and I talk about managing it and understanding it and making sure the building negotiates the challenges of belonging, it’s poetry. And that is also what happened with the wool shed: the new wool shed we are doing at Armidale it is different from the one we did at Wagga Wagga.

SC: It’s a different place.

PS: It’s different country and so our functional response remains but our qualitative response differs. Using the same technical aspects, but moderating how it sits and manages its local environment.

SC: If I look at the wool shed; at the hangar and it seems to give you a great liberty. Having followed your work for many years, I feel like you know better than most about the elemental nature of putting a building together. Not just pure construction – you can get that from a book – but fundamentally understanding how you can look at a material or a proprietary item and you can think of many different ways to use them. The chicken-house louvres for example, your ability to make, compose and put things together. It gives you a great licence to be inventive.

PS: That’s a really interesting comment. I did a talk on this the other day, on elemental – when you manage the elemental, the advantage is experimentation.

If you go into something experimenting without the elemental it can become problematic, because the way you begin to solve is unknown. Sometimes a discovery could be costly and disconnected. But if you use elemental techniques to begin to solve the problem, the discovery may be logical. It’s a bit like handing on that wisdom we were talking about earlier, if you refine the wisdom hopefully there is discovery. But if you start with the discovery then how do you integrate? Or how do you think about it, or how do you explain it?

I use the word elemental a lot in terms of how we do things now. So the house we are building for ourselves is incredibly elemental. Possibly our most elemental, other than the tent. Because what we’re trying to do is reduce elements back to the obvious. Say you want protection on the coast, a tough masonry element makes sense. But you also want connection, like a tent, so you can retain the quality of camping. Put those two elements together, which are almost the opposite in terms of materials, and you have this incredible building that is on one hand a shellback cramped against the wind and on the other hand is a blade of grass, blowing in the wind. That’s the discovery.

SC: I guess being elemental and fundamental is about knowing the rules. Once you know and understand those rules, you can break them.

PS: If you don’t understand prose and punctuation, then your poetry makes less sense.

Perhaps it can be distilled to one word, and that word is respect. Once we learn to respect the land and people, I think our work and our nature – the nature of who we are – becomes incredibly responsible. It’s not sustainability we should be aiming for it is responsibility.

For a full transcript of this interview please visit architecturebulletin.com.au