In 1907 the Bendigo Advertiser reported on the increasing use of concrete in building construction, stating this era was to be an ‘age of concrete’. From the late 1890s onwards the Professor of Engineering at the University of Sydney, William Henry Warren, tested building materials. His experiments were well known throughout New South Wales, but as the Clarence River Advocate noted, his work in the testing of reinforced concrete was new to the world. In early 1905, the use of concrete in buildings was under discussion at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), however, use of ‘ferro-concrete construction’ was still restricted in London and had only been used in buildings erected by dockyard companies and in railway yards.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake provided a valuable architectural lesson for other cities: reinforced concrete fared better than traditional masonry construction, which suffered considerably in the quake and subsequent fire. New South Wales architects were well aware of which type of buildings survived the quake; in reports on the new Globe Hotel in Albury (1909, designed by J.T McCarthy), and the Criterion Hotel in Newcastle (1912, by Eaton and Bates), the San Francisco precedent is mentioned.

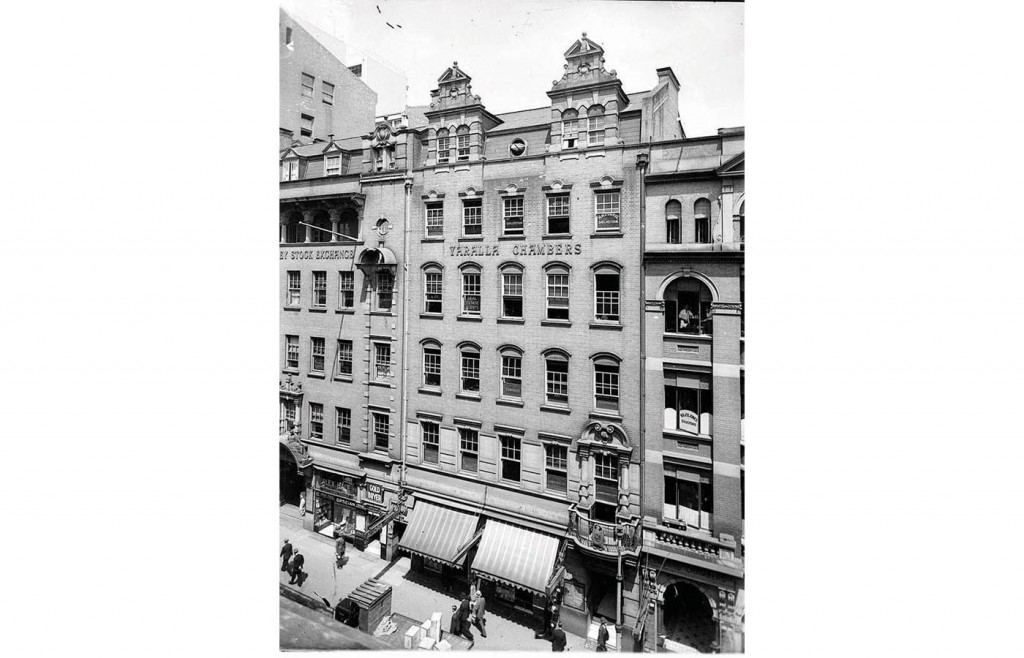

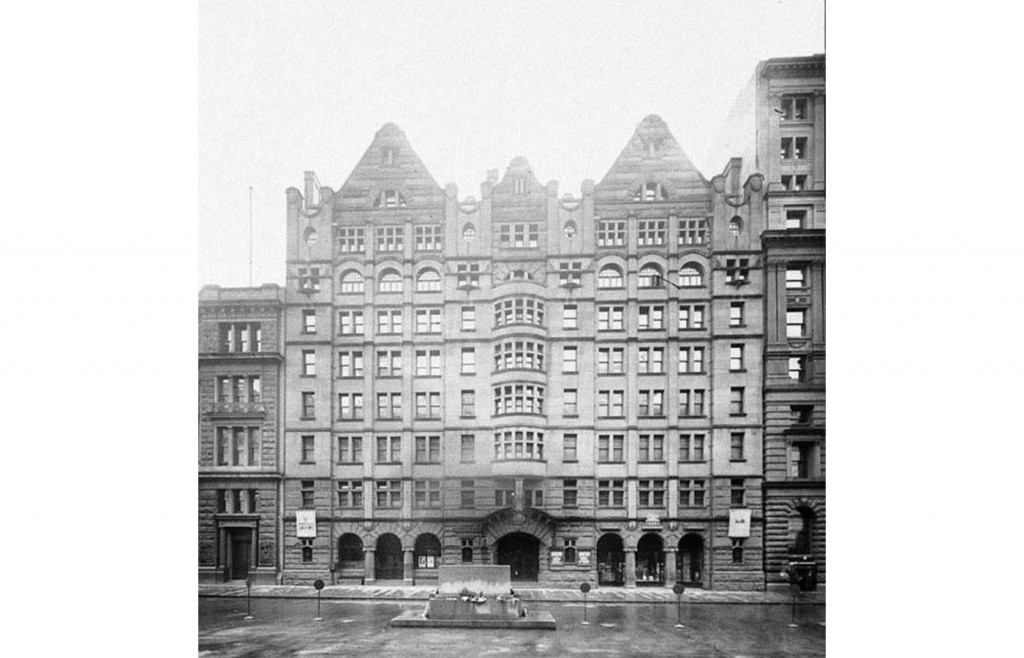

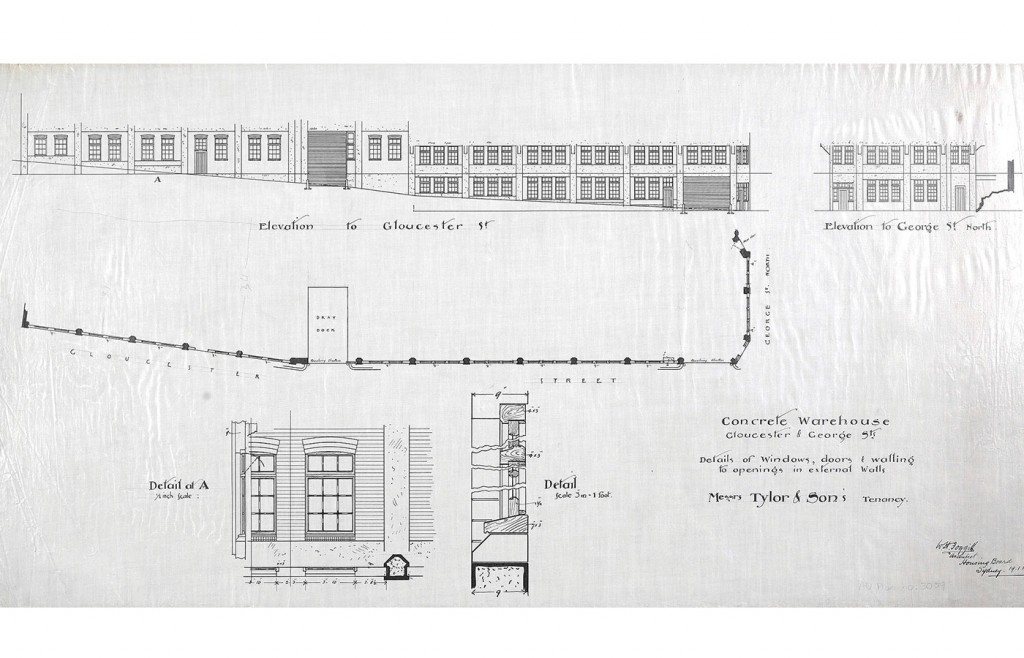

By 1906 the firm of Kent and Budden and the architect Herbert S Thompson were each employing concrete floors for commercial buildings in Sydney. Thompson died suddenly in 1907 and his quirky Lombard Chambers in Pitt Street (1905‒1906) have since been demolished, however, the exposed steel sections on the facade would have appeared revolutionary at the time. It is probably no coincidence that architects who advocated the use of concrete had their offices in new fireproof city office buildings. Eaton and Bates, the architect J.T McCarthy and the architect and civil engineer John Jasper Stone all had their offices in Challis House. Erected in 1907, Challis House in Martin Place was intended to be as fireproof as possible, employing concrete floors and concrete-encased stanchions. Funded by the Challis bequest and erected to designs by Robertson and Marks (in conjunction with the NSW Government Architect), Challis House was built for the Senate of the University of Sydney. Concrete stairs and floors were then used in a series of public schools designed by the Government Architect’s Branch in 1908 including Annandale South, Arncliffe, Gardeners Road in Mascot, Tempe and North Newtown.

The Bathurst Post reported in June 1907 that large quantities of reinforced concrete were being used in Sydney buildings. The following month James Nangle invited the NSW Institute of Architects to witness tests on concrete beams, which were undertaken by the Department of Architecture at Sydney Technical College. Among the architects who attended were those who had already been using concrete for fireproofing: Harry Kent, his partner Henry Budden, and George B Robertson of Robertson and Marks.

In city buildings the transition from hardwood posts to concrete construction methods occurred in the years leading up to World War I, and can be seen inside Sydney’s Federation-style warehouses. Bennett and Wood’s warehouse, factory and shops, designed by Harry Wilshire, were erected on the corner of Pitt and Goulburn Streets in 1908. Internally the lower floors were supported by concrete-encased steel stanchions, whereas the remainder of the building had more traditional hardwood posts. The stair and window heads were reinforced concrete. The building, which survives, had goods elevators, sprinklers, and a rooftop ‘recreation reserve’ and dining room for staff.

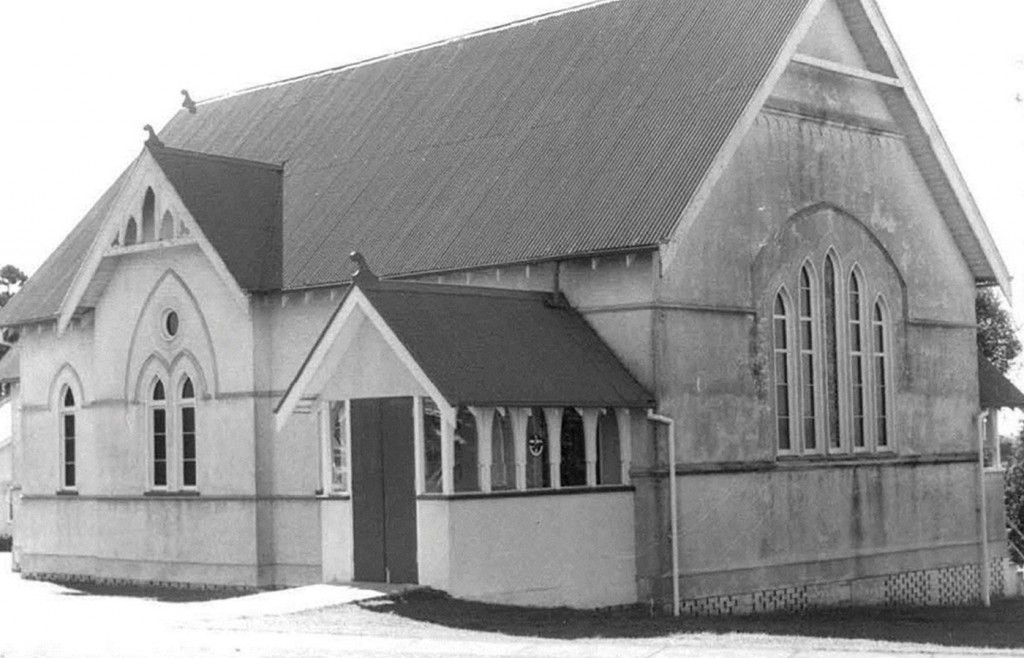

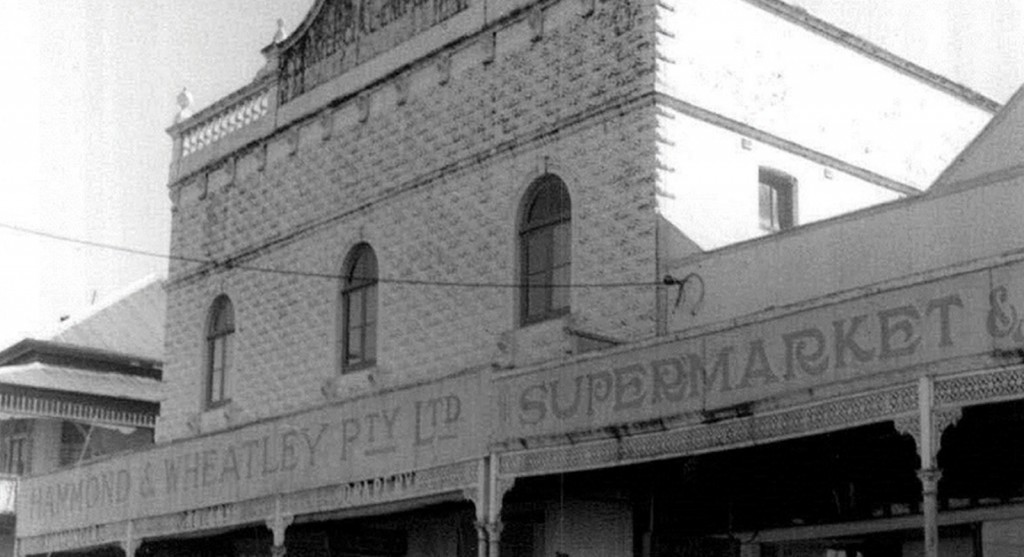

Innovations in the use of concrete were not confined to Sydney. By 1905 concrete floors were being used in institutional buildings in country New South Wales, such as the Roman Catholic orphanage at Kenmore designed by the Goulburn architect E.C Manfred. As a young architect, Harry Ruskin Rowe, then working for Spain and Cosh, the architectural firm that his late father had established, supervised the construction of A.G Robertson’s new Red Flag Store in Lismore. Erected in 1906 this store had concrete block foundations and steel-encased stanchions. Ruskin Rowe retained an interest in the possibilities of concrete, one of the first tenders in early 1912 from the newly created partnership of H.E Ross and Rowe was a substantial reinforced-concrete stables block in Pyrmont.