table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

Imagine a City: 200 years of public architecture in NSW

There was a sense of irony in attending the opening night of Imagine a City: 200 years of public architecture in NSW at the State Library of New South Wales. At the same time as celebrating this achievement, the Government Architect’s Office (GAO) was transitioning from a design and construct role to one of strategic design advice only. The office was downsizing from eighty to a core of twelve and had moved into the Department of Planning. They would no longer be designing and constructing buildings – yet here we were celebrating 200 years of built work.

The exhibition was part of a yearlong program called GAO200+, commemorating the extraordinary built achievements of the GAO, one of the oldest architectural practices in the world. It featured a rich and rarely seen collection of original drawings, photographs, plans, paintings and models from both historic and contemporary times.

It was on display at the State Library from 20 February until 8 May 2016 and was curated by Dr Charles Pickett, Matthew Devine and Margot Riley. As a method for exploring the body of work, the exhibition was structured under a series of themes: future, law and order, learning, city, landmarks and culture. A timeline celebrated each of the twenty-three Government Architects, from colonial Francis Greenway to today’s GA Peter Poulet, referencing notable works completed under their stewardship.

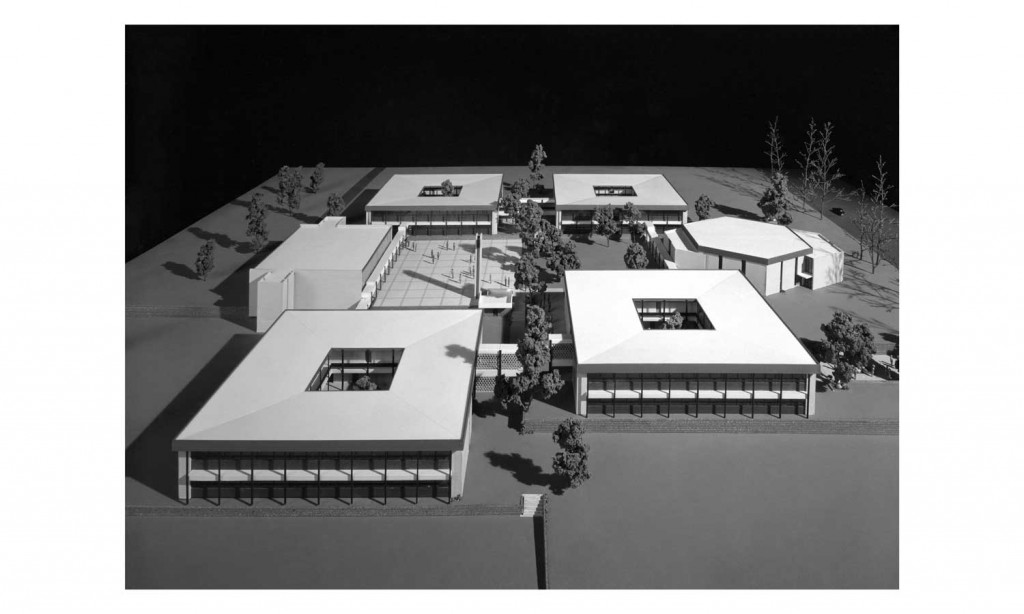

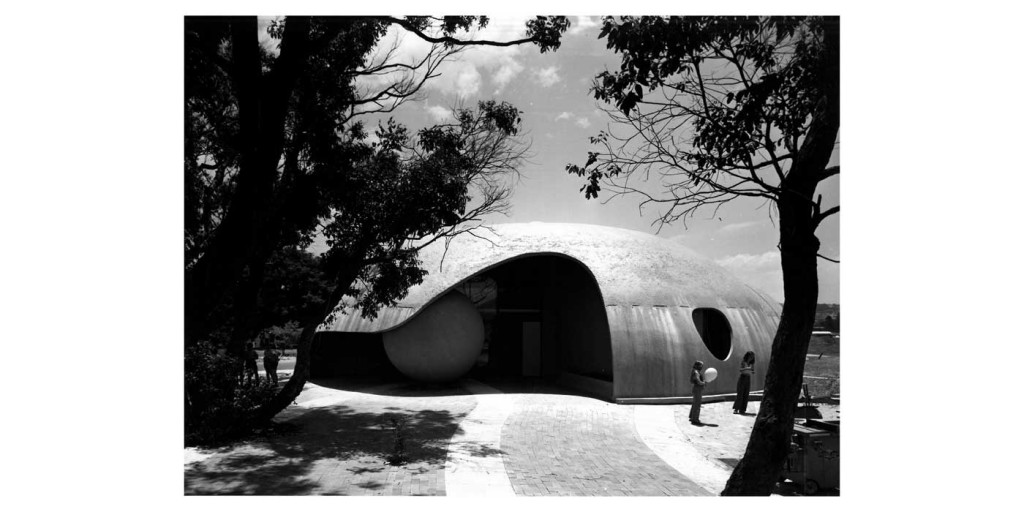

Within clear constraints, it was an excellent exhibition, but considering the breadth and quality of work completed, it was far too small to give due credit to the portfolio. Despite Peter Poulet’s statement in the official brochure: ‘buildings can be fearless, buildings can be of their time and buildings can be controversial’, it was a very safe exhibition with few examples of fearlessness or controversy on display. A short video on how Ian Thompson brought Dante Bini to Sydney and introduced fourteen of Bini’s shells to the schools program is fascinating. As was Michael Dysart’s simple but revolutionary concept known as the ‘doughnut plan’, to wrap school classrooms around a central court. The exhibition needed to show us more of this type of research and experimentation. It is hoped that a detailed monograph will be assembled to complement the exhibition, as the booklet provided as a memento was not nearly detailed enough.

Some history

When Governor Macquarie appointed Francis Greenway (1816–22) Civil Architect in 1816 – effectively commencing the 200-year tradition of the Government Architect – there was a clear need for the role, as a reliable private alternative did not really exist. (Notwithstanding that Greenway had set up private practice prior to his appointment and continued to maintain his practice whilst in the role of Civil Architect).

The position was a stop-start affair to begin with. Standish Lawrence Harris (1822–24) and George Cookney (1825–26), the second and third Colonial Architects (as they became named), did very little and the role was then abandoned from 1826 until Ambrose Hallen (1832–35) was appointed in 1832. At the time the Board of Works believed the position was unnecessary as private architects could be commissioned as the need arose, an argument that has returned continuously, often strongly lobbied by private practice.1

After Greenway, Mortimer Lewis (1835–49) and Edmund Blacket (1849–54) stand out amongst the early Colonial Architects. Blacket had a successful private practice before being appointed and ‘advocated the design of public buildings by competition among private architects’.2 During his time, he was responsible for few public buildings and returned to private practice to complete his seminal buildings at the University of Sydney.

During the time of Blacket’s successor, William Weaver (1854–56), a public inquiry was conducted that led to major reforms of the office due to apparent corruption at many levels.

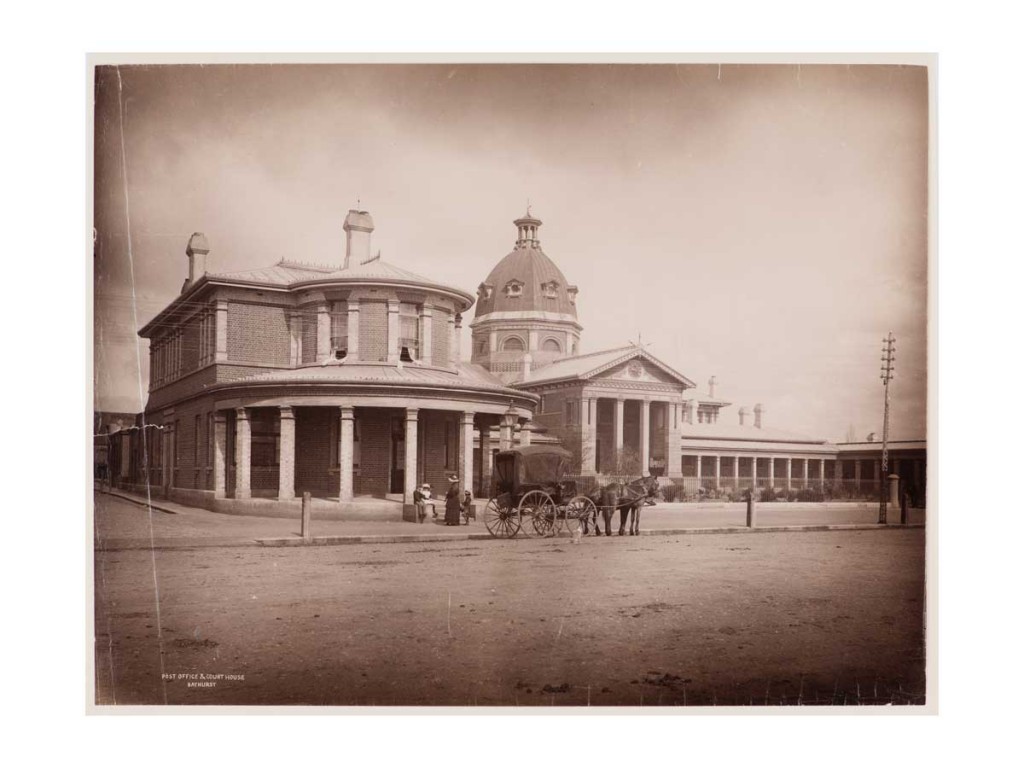

More than any other James Barnet (1862–90) has left a significant built legacy across the whole of NSW. During his twenty-eight years in the position, he built up the office from a staff of seventeen to sixty-four by the time he left. The work was not just prolific, but it symbolised a period of confidence and economic boom and marked the graduation of Sydney from Georgian settlement to Victorian city. Barnet and his successor, Walter Liberty Vernon (1890–1911) occupied the role for nearly fifty years between them. This period represents one of the two golden periods of the office; the other being the 1950s to 70s.

Despite Barnet’s apparent success, and in part because of the extraordinary office output, there were constant reviews of the office performance and pressure from the competition lobby for public buildings to be procured through design competitions amongst private architects.

At the end of Barnet’s tenure, the government had decided again to abolish the position of the Colonial Architect’s Branch. This could easily have been when the role was abandoned for good, as was happening in the other Australian states at the time as many believed the need for the office had run its course.

Abolition lasted little over a month before Vernon was appointed Government Architect, the first time this term was used. His brief was to oversee a new competition policy for public buildings that only lasted two competitions.

When William Lyme, Secretary of Public Works, intervened in the competition for a new insane asylum near Goulburn by supporting an entry by architect Kirkpatrick (a close friend) over the winning scheme by Sulman and Power, a scandal followed that meant abandonment of the competition policy. This effectively cemented the role of the Government Architect for the next 100 years.

The second golden period commenced under Cobden Parkes (1935–58) and his senior design architect Harry Rembert. Rembert was influential in introducing the ideas of Modernism into the office.

After Parkes, Ted Farmer (1958–73) and Rembert reintroduced Barnet’s Room System, where architects specialised in particular types of design. The office grew in size and importance, reaching 1300 staff spread across Sydney and regional areas by the time Peter Webber (1973–74) took over. The office became multi-disciplined, with the integration of engineering, landscape architecture, urban design and heritage.

The GAO, in particular the Design Room, was the place to be for young and talented graduates, and traineeships were very competitively sought. By the late 1960s there were 1500 applications for twelve positions. The Design Room was described as an ‘atelier in the true European sense of the word’.3 Peter Webber, Ken Woolley, Michael Dysart and Peter Hall were the initial ‘Young Turks’ of the 1950s, and many others followed through the 60s and 70s, with some moving on to significant careers in the private sector. It was during this period that the longstanding tradition of attributing design only to the Government Architect was relaxed and the project design architect was allowed to be identified. This was important in raising the profile of young architects within the office and assisted them in establishing their private practices.

When architects reminisce on the good old days of the GAO, it is probably this period that they are thinking of. The office was producing some of the most experimental work in the country and since 1962, when it first started entering in the RAIA Awards, it has received more Sulman medals than any other practice. The reputation of the office was the envy of the world, and combined with the private work of the Sydney School in the 60s, it was a formative period for Sydney’s architecture.

By 1988 when Lindsay Kelly (1988–95) was appointed, it was an era of restraint with the newly elected Liberal Greiner Government. Under the push for economic rationalism, it was assumed that the private sector could always do better. This really represents the beginning of the end for the GAO as we know it. Combined with the Fee for Service approach, the office transitioned into a semi-commercial practice, competing with private firms for public work. This was never going to be sustainable in the long term, nor was it ideologically sound.

What is clear from the above potted history is that the role of the Government Architect has continually adapted over the 200 years of its existence. Various public building typologies have moved in and out of its brief. There have been consistent reviews over the quality of work, management practices, governance and even the need for its existence. It has not been immune from corruption and incompetence. And, there have been constant calls for public buildings to be procured through the private sector. What has been consistent is that it has had a strategic advisory role to government while also being a functioning architectural practice.

Legacy

There is concern that much corporate knowledge will be lost in the restructure of GAO. Whilst some may argue that it will just be redistributed amongst the private sector, it is not quite the same thing. A heritage architect working in a commercial practice and one working in a government office perform very different roles.

Putting aside the real emotional wrench and tragedy of staff being retrenched – what does it mean to make this restructure? Restructures happen across government departments and the commercial sector on a regular basis and for a range of reasons. If the reasons are sound, and assuming that those retrenched are treated fairly, then restructure should not be opposed simply because there is an emotive response to keep doing things the way they have always been done. The transition from a ‘doing’ office to an advisory role was set in train when the Liberal Greiner government took power; it has just taken twenty-eight years for the process to be completed under the latest Liberal government. Just to remind us of the norm, the exhibition booklet notes, ‘in western nations government buildings are normally the work of private architects selected through competition, tender or patronage’. However Peter Reynolds in his PhD thesis of 1972 on the evolution of the Government Architect’s Branch from 1788 to 1911, writes of the ‘contributive importance of the Branch to Australian Architecture and its singular uniqueness in world architecture’.

Just to remind us of the norm, the exhibition booklet notes, ‘in western nations government buildings are normally the work of private architects selected through competition, tender or patronage’. However Peter Reynolds in his PhD thesis of 1972 on the evolution of the Government Architect’s Branch from 1788 to 1911, writes of the ‘contributive importance of the Branch to Australian Architecture and its singular uniqueness in world architecture’.

‘Is there a need for a GAO that designs, documents and oversees work? Arguing that there is no longer a need is perhaps akin to saying that there is no need for the ABC to make TV or radio, as perfectly good programs are made by the commercial media’

In an interview with Richard Johnson included in the exhibition he says, ‘to say that private enterprise can do what government can do … I don’t think they can entirely’. Johnson uses the example of his own office, JPW, where unprofitable public work is in effect paid for by the profitable commercial projects.

The real question remains: is there a need for a GAO that designs, documents and oversees work? Looking beyond the GAO, there are clear examples of government-funded work that has and always should be wholly managed within the public sector. Few would suggest that our police or military forces should be contracted out and replaced by private militias and mercenaries. There are also examples where we accept that the government has a part to play in partnership with the private sector, such as healthcare, where public and private hospitals complete the system.

Arguing that there is no longer a need for a GAO producing work is perhaps akin to saying that there is no need for the ABC to make TV or radio, as perfectly good programs are made by the commercial media – and that is a debate that is currently being pushed by parts of the conservative right.

How often have programs commenced on the ABC, only to be picked up by the commercial stations later on? How much poorer would our cultural landscape be if the ABC and SBS were to be reduced to an advisory role?

There is a strong argument based on the historical record to suggest that the enhanced role of the GAO in NSW gave it the ability to influence and advance architectural practice as a whole, as often it would lead the discourse, being in the rarified position of being answerable for the results of its output, not just the commercial viability.

Conclusion

Imagine a City was important for all who care about public architecture. Not just as a history lesson, but for understanding the power of continuity in design excellence and for thinking about what the current changes to the GAO mean for this legacy.

One wonders what is the level of continuity between that historical legacy and the GAO’s new role. Will the office have the same level of credibility when it is no longer setting the example through design and construction?

I predict that the shift away from a ‘doing’ office to a strategic role will be temporary. At some time in the future, either through a change of government or constant complaints from government agencies that the private sector does not understand the specialised nature of what is needed – the argument will resurface that some work is best handled by the public sector. The GAO will then re-emerge as a specialised office with a targeted role on specific projects, whilst maintaining its strategic advisory role. This is exactly what happened in the 1890s, and probably this cycle will continue as long as we continue to build public buildings in NSW.

Andrew Nimmo is director of lahznimmo architects and is adjunct professor, Architecture, Design & Planning at the University of Sydney

Notes

1. Government Architect’s Office Preliminary Historical Outline – 19 February 2015, p 1.

2. Ibid, p 10.

3. Russell Jack, ‘The Development of the Government Architect’s Branch During the Time of EH Farmer’, Thesis for Diploma of Architecture, UNSW, Vol 1, p 10.