table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

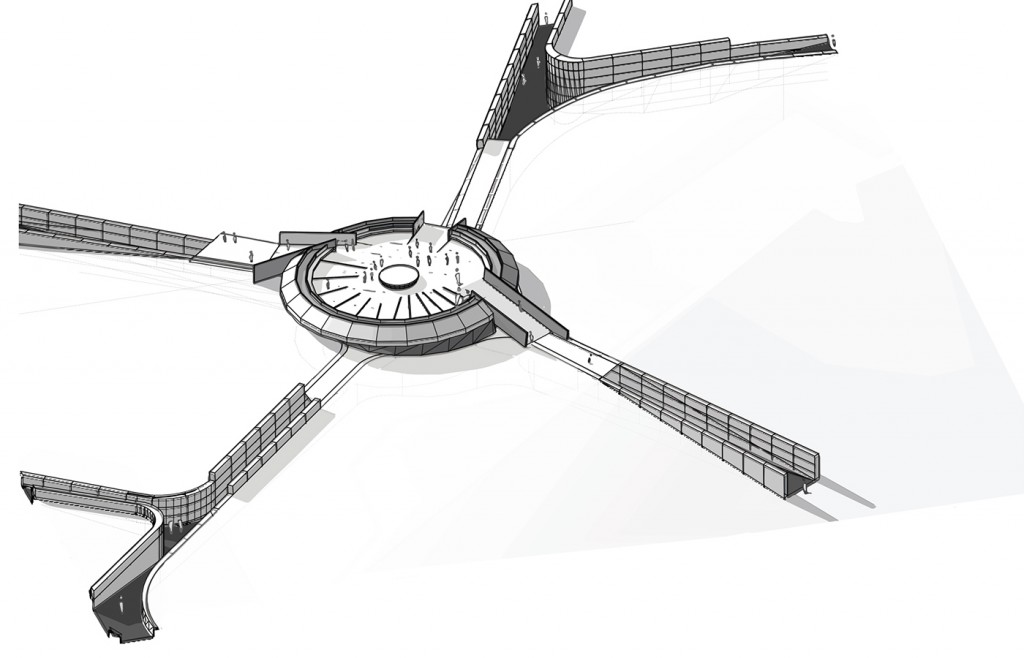

- Perspective view of proposed semi-underground bushfire safe community centre/shelter. Image: Ben Wollen.

CONFLICT ON THE PERIPHERY

An Investigation Into the Urban Renewal of Bushfire Ravaged Areas

The 2013 bushfires that devastated the community of Winmalee in the Blue Mountains provided the focus of Ben Wollen’s investigation into the urban renewal that occurs after a major bushfire event. As the recipient of the Institute’s 2014 David Lindner Prize – a $5,000 grant towards research related to architecture in the public realm – Wollen has undertaken primary research to inform his development of a community-focused architectural response to the redevelopment of the area that could improve its future resilience to the increasing risks of catastrophic bushfire events.

“Quite often, when you’re in an area that’s been hit by natural disaster, post conflict, or is amidst a blight of systemic poverty, people see despair…but when architects go there, they see an opportunity to change, they see an opportunity to resurrect a community. This is the value that we [architects] have that can truly transform a nation and transform a profession.” Cameron Sinclair, co-founder of Architecture for Humanity. 1

The act of architecture is in its essence an act of optimism. The architect envisions a new future with every project; one that is full of new possibilities. This is in stark contrast to the climate scientist who studies the past to determine the future. One such climate scientist, James Lovelock warns that if predictions are realised, the future may be a place where an act of optimism becomes an increasingly rare occurrence. In his books, The Ages of Gaia and more recently The Revenge of Gaia2, Lovelock developed a theory that the Earth is a complete living system that self-regulates in order to keep life on the planet viable. Lovelock urges immediate action to build resilience into our existing infrastructures in preparedness for the extremes of climate change.

What does Lovelock’s position on the dire situation of the future mean for the built environment and the optimistic act of architecture?

It was this question, along with a focus on extreme bushfire events, that directed my research undertaken with the assistance of the 2014 David Lindner Prize grant.

The occurrence of extreme bushfire events, such as those experienced on Black Saturday in February 2009, is on the increase. We are already experiencing an extension to the traditional bushfire season, one example being the bushfire that tore through the township of Winmalee on 17 October 2013.

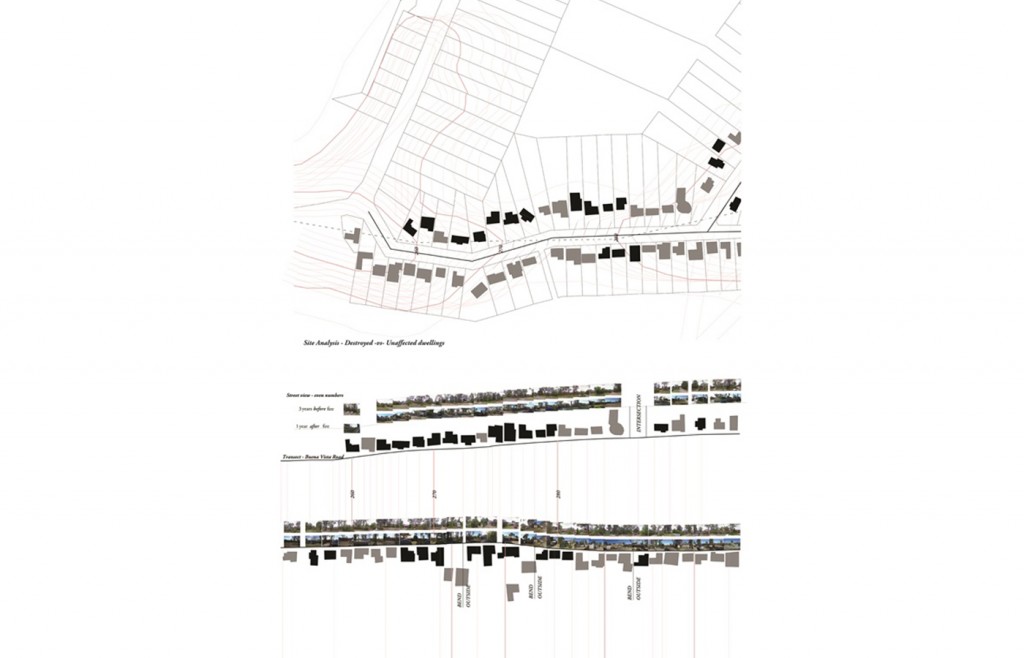

During this bushfire event, a total of 193 houses were destroyed and a further 109 partially damaged in the Springwood area. On Buena Vista Road, the focus of my study, more than 40 per cent of the houses were destroyed. This has caused severe trauma on a community scale that will endure for a considerable time. However, it has also provided the impetus to galvanise the community and strengthen the bonds between friends and neighbours who have come together to heal the physical and emotional scars left in the bushfire’s wake.

My initial mapping investigations into the area of Buena Vista Road, reveals the western flank of the road as having suffered higher losses than the eastern flank. This can be attributed to the steep ridge just below and in the direction of the fire front. The road itself also provided a protective buffer to the eastern flank as the fire front came from the west.

Using Google Maps Street View, I have completed a comparative survey of historical photographs of the street, comparing a first set of photos taken three years before the fire with a second set taken one year after the event. This reveals some correlation between the houses destroyed and the extent of vegetative cover. However, other factors such as building form or size (two storeys vs. single) appear to have had no significant correlation with the houses destroyed.

A CSIRO report on the Springwood fire3 indicates that most damage occurred as a result of ember attack. The report reiterates the role of the steep terrain of the Blue Mountains area in increasing the number of houses destroyed. It also indicates a higher survival rate for those buildings with metal fascias.

In addition to my primary research, I have also collected information from secondary sources on the Black Saturday event. The scale of impact of this particular event and the devastation it caused in terms of loss to buildings and human life has caused a worldwide rethink on how to deal with such catastrophes, both before and after they occur.

Recollections from some of the survivors of the Black Saturday fires reveal that even a well-designed house and a prepared household cannot guarantee safety and survival in the face of severe firestorms. The Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre4 recorded a number of interviews with survivors who were seasoned locals, born and raised in the locality, and who had well-prepared bushfire plans. Despite their local knowledge, experience and preparedness, when faced with the extremity of the Black Saturday event, they decided to flee when they saw the fire front from the house they had intended to defend. Fleeing at this late stage is hazardous, and results in many fatalities.

Many locals, for lack of any other escape, made their way into the centre of their local town and took shelter at makeshift refuges, such as sports fields or the local fire station headquarters. There, they rode out the firestorm in the company of other community members, and with the somewhat safe feeling that the local fire brigade was on hand.

The act of communities choosing to shelter together in the face of an approaching fire front provides the stepping stone to the design component of my research.

In the face of catastrophic bushfire events the individual household bushfire plan is rendered ineffectual, putting the lives of those who stay and defend in peril. It is argued that on these extreme occasions a community bushfire plan is required at the neighbourhood level. This is especially the case in the cul-de-sac communities of the Blue Mountains, which have only one way of access in and out, and can be easily cut off from assistance if a fire jumps the road.

In my project, this understanding has led to the design of a community bushfire refuge for extreme bushfire events. It provides a safe destination for those who decide to flee late in an extreme firestorm. After the fire front has passed, those who are well prepared and able can return to put out any spot fires on surviving buildings. This community bushfire refuge can also double as a community centre at other times. It will provide a hub for community activities and a location in which the local community can come together to collectively prepare for bushfire events.

We are entering a new era of our understanding of bushfires. There is a lot to learn from the traditional owners of this land and their use of fire as a land-management tool. However, with the increasingly unpredictable effects of climate change and the never-ending expansion at the periphery of our cities into remnant bushlands, the protection of life and home is becoming much more complex. It took the Indigenous population many thousands of years to evolve a balanced relationship with nature. This may not be achievable for some time if we take Lovelock’s position. Perhaps in the immediate future we have to look for a sustainable resilience.

FOOTNOTES

- Quote from Cameron Sinclair’s address at the 2013 American Institute of Architects Conference, Denver, US. http://www.archdaily.com/392777/aia-2013-citizen-architect/

- James Lovelock, The Revenge of Gaia: Earth’s Climate Crisis and the Fate of Humanity, Basic Books, New York, 2006.

- Glenn Newnham, RaphaeleBlanchi, Justin Leonard, Kimberley Opie, Anders Siggins, Bushfire Decision Support Toolbox Radiant Heat Flux Modelling: Case Study Three, 2013 Springwood Fire, New South Wales, CSIRO report to the Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre, 2014.

- Jim McLennan, Use of Informal Places of Shelter and Last Resort on 7 February 2009: Peoples’ Observations and Experiences – Marysville, Kinglake, Kinglake West, and Callignee, Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre, Victoria.