table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

- David Pitchford.

Against Mediocrity

Shaun Carter and David Pitchford discuss alliances and innovation in the battle to achieve exceptional urban development.

Shaun Carter (SC): I think I saw you on the 28th of 29 presentations at the Sydneysiders Summit. It looked a big effort.

David Pitchford (DP): Yes, it was a long four days – no question about that. It was a very successful outcome that raised very significantly the stakes for us regarding the trust of a range of organisations and communities. It was very successful.

SC: I have to say largely the feedback that we’ve had is: ‘Isn’t it wonderful that a government agency is talking to the people, isn’t this wonderful that we’ve been involved in the conversation?’ I guess that when you pose a question rather than saying: ‘This is the outcome’, people engage with the question. It doesn’t become this binary thing – either yes I want it or no, I don’t. Oppose or accept. It becomes a broader open conversation about what could be. People feel like they’re part of that conversation. For a delivery agency which you guys are, I guess that becomes easier to then bring projects to fruition.

DP: The scale of the undertaking is such that you just can’t do this as a delivery agency. It’s going to have to be done through partnerships. But no partnership is going to succeed if it starts from an atmosphere of distrust and if that distrust is actually so poisonous that it’s warfare. We’ve set about over the last year or so trying to turn that proposition around and we’re on a trajectory, but with so much more to do. The two massively important summits were really about sending a signal. We want to operate at a different level, in a different way, to achieve different outcomes.

SC: So how would you describe the role of UrbanGrowth NSW to the architecture profession?

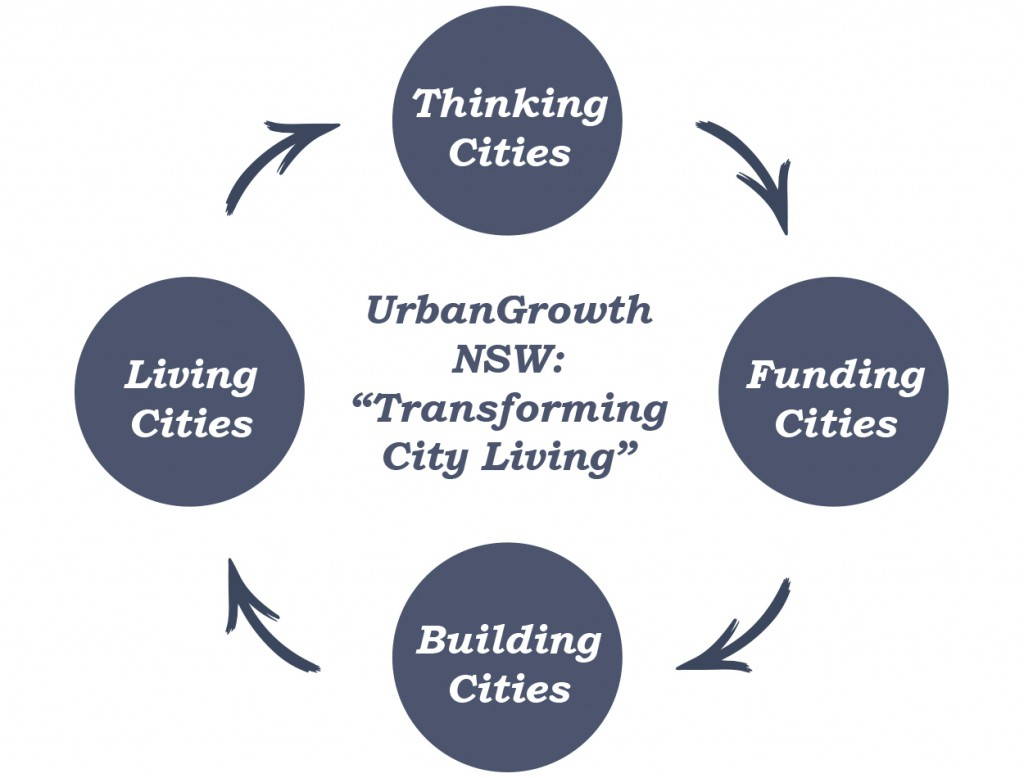

DP: The role of this agency is to go where no one has gone before and to actually achieve some outcomes that have been crying out for 30 to 40 years. It’s an agency that is both a delivery and a design agency. We have this very important, different city transformation life cycle model (see accompanying diagram) which you would have seen in the summits, which is not only a diagram, it’s a philosophy. It underpins our business plan. It underpins our work approach and it also will underpin everything we do in terms of the priorities for the projects.

Our work is not just about development. It’s about economic growth. Our overall thrust is to drive an internationally competitive Sydney in terms of its economy, its liveability and opportunities for all Australians. It goes way beyond just some development platform similar to Barangaroo for example, which is a fine project, much maligned, but ours is a much, much more extensive responsibility than just taking a piece of land and converting it into a project.

What we’re transforming is Sydney Harbour and the lives of Australians and that’s all about economics and job growth. We want to create new jobs, real jobs. We don’t want just to decant people from other parts of Sydney.

What I want to do is to create a mass of new exciting undertakings, particularly in information-based jobs that will attract people from all over the world, all over Australia, to come and do things that are certainly different for us, but also everything that goes with that. If you want to attract talent, you’ve got to provide a platform, you’ve got to provide places to live that they love and we’ve got the opportunity to do that here.

UrbanGrowth is possibly the most important partnership platform that the Institute of Architects has ever been associated with, because we are looking to you to be allies in the war against mediocrity.

The difference in our delivery model is that we will stay involved. We won’t set up the delivery platform and then hand it over to a consortium and see what happens. We will control the elements that relate to ‘design, build and develop’. The reason we want to do that is because we want to build great places and great spaces and that is going to be fundamental in a place like the Bays Precinct.

In relation to Central to Eveleigh, we’ll be looking for your members to help us innovate to the point where we do things much, much smarter, much more effectively and we address the density issue together.

I see your membership and the design capability that it has as being a beacon for us. We’re not going to settle for the cheap and easy designs, the knock-offs as I call them. What we want to do is to reach those elements of your profession that want to join us to make certain that we build great things, particularly at The Bays, which is possibly the most high level and high potential urban renewal site in the world, given its proximity to the Sydney CBD.

SC: Such a rare opportunity too, 80 hectares of land at the Western edge of the city.

DP: It’s an absolute obligation on us to do that in the best possible way, not the easiest way. That’s why we started with the model. We start by thinking first and working out what the aspirations, ideas and needs are. That’s the first stage. We look then to see how we are going to fund it and we are well advanced into some pretty innovative funding models. Only then do we go to the building phase, but when we get there, it’s not just about design, it’s about the design of what, where and why and how. Is it linked to infrastructure or what additional infrastructure does it need? For example, in The Bays, there is nowhere near the transport infrastructure that needs to be there.

We’ve got to address that really important question of mass transit and introduce a whole range of things that will be unpalatable to the government in terms of the level of investment, but without that, it will be a disaster.

We also have some fantastic opportunities there to be innovative. The White Bay Power Station is the last of its kind. We’ve got an obligation to use it, but it’s got to be used in a way that drives economic outcomes in my view. I feel strongly that we have an opportunity there to utilise a piece of history to develop what might be great for the future. I’m not wedded to it in terms of ‘it must be preserved’. It must be used. The difference is really important.

We will manage the development process, but we want to be an alliance, not just a commercial partnership. There’ll be lots of people within your profession that will just say: ‘Well, this is just more government mumbo jumbo’. When you see us get out in the market place to secure the people that we want to design and build this, you’ll see it differently. We are simply not going to settle for the same old models.

SC: I think everyone in the architecture community I speak to is really enthused about UrbanGrowth. Particularly the way you’ve launched and the way there’s this open conversation. We’re particularly interested in diagrams like your life cycle model. They’re not linear, they’re circular. You understand that cities are dynamic places. They grow, they change.

DP: A 25 year project never ends because what you’ve got once you get to about the 10 year mark has to be re-invented to see whether the currency of it is still there, have we got it right? If you’ve haven’t got it right, you start to correct. This is a dynamic that will go on forever because even after 25 years, that’s a notional point in time as opposed to an end point.

SC: Really with cities, there is no end point until the civilisation has gone.

DP: Until there is some catastrophic happening that changes everything.

SC: You mentioned allies, and I think the profession would be more than willing to ally with UrbanGrowth NSW to deliver the best design and I think that plugs into what you were saying earlier. Sydney is a global city, we are growing pretty quickly so we need to think about how that happens, so the Institute has this idea of bigger and better, not just bigger.

I like what UrbanGrowth NSW is saying about making communities, because if we are going to attract talent over and above San Francisco, or LA, or Hong Kong, or Jakarta, or anywhere in the Asian basin, we want people to come here and say: ‘Look, it’s a great place to live, I know that, but is the housing up to it?’

We know that SEPP 65 is heading down the path towards world’s best housing. That’s going to be a big tick in the liveability index and then I guess the next thing is, is it an attractive city to look at and what about the spaces between the buildings, the public domain? They’re really vital.

DP: It’s actually going to be crucial to our operating model. You know Jan Gehl and his edict that ‘great cities have great buildings, but truly great cities have great spaces’. If you think of the great cities around the world they do have great buildings, but they also have fantastic connections and great spaces that people can enjoy. What we need to do here, and this is where your profession can be very masterful, is to start to think about how we build to attract people who want to go past the physical beauty. We want them to come here because of what they might do here, what they might enjoy here, how they might feel living here.

There have been great inroads made here in terms of what’s been a massive issue over the last 35 years and that is, the death of the city at night and weekends. There’s more, much more that can be done, but the development of high density smartly designed and even more smartly built places in areas around here is really crucial.

With the arrival of Barangaroo, the west of the CBD is ‘now complete’, but we could go further west into The Bays. But in terms of the CBD itself, the only way that can grow is south and up, and we need to do both of those things. That’s why Central to Eveleigh is so important. What we are hoping for, and the Urban Taskforce is well into this proposition, is to get really smart with the use of height and start to elevate our thinking about the elevation of our building.

Think about some of those fantastic developments that you see in New York now. The late Paul Katz and I had a bit of a design affair for about three months before he died. He came out here and we talked a lot about the proposition of the pencil tower that you see now starting to come out in New York.

SC: SHoP architects are doing one at the moment. They’re doing 60 meters by 80 meters, but 440 meters tall.

DP: Yes, that’s exactly right. You get much, much less mass on the ground, therefore more space and it spreads out as it goes up and you get the premium accommodation. You still get the retail and the mix, but you don’t have this mausoleum type of effect on the ground.

SC: I love New York City because it makes proper streets and it’s a walkable city. Small lot sizes with tall buildings works perfectly fine. You get that wonderful variegated street. You get some mega blocks in New York City, but there is also a lot fine gain there because it’s evolved over time.

DP: The fine grain stuff is really important to us because we want this diverse offering. We want high density, but a high success level as well. We don’t want to have lots of apartments that are in a junkie area. We want things that are really great and we want things like Central Park in Chippendale, where people are really excited about the buildings as well as being excited about living there.

The other element that’s really important for us in this respect in terms of the architectural impact is that we start to develop a platform where your profession understands what we are about. What’s really important here is the alliance that we have with the Government Architect. We have really strong relationships with them. Peter Poulet is part of our operation. He will sit and chair the design commission once we start on The Bays development phase. We’ve got a constant association within our organisation with one of his senior architects, Ben Hewett, and of course we’ve now got Ken Maher on our board.

Ben is involved in the Call for Great Ideas, he was involved in the summits, he is involved in forward planning advice too. The importance of the profession can’t be understated in relation to what we want to do, but we are looking for a fresh approach in the war against mediocrity, and I don’t mean that as some sort of evangelist, but I am determined that what we leave in The Bays is as good as it can be and that the other developments in other parts of the city are equally good as well.

One of the great learnings from New York – and places like Toronto – is that you start with the public offerings. 10 years or so ago it was hard to get around New York, but now you can walk the entire river from Battery Park all the way to the George Washington Bridge. That’s what we should have in Sydney and that’s what we are driving for, so you can walk all the way around the harbour. In New York they’ve realised that by providing great public spaces, it actually provides an uplift to the values of the places around it.

SC: It’s already a reason for being, isn’t it? It’s already a reason for people wanting to go there.

DP: If you’ve got great public spaces, or great patches of open space, then you can design for it – as opposed to the Tokyo approach where they don’t have parks because they haven’t got room for them. We need to be the opposite.

SC: It’s a bit like saying we don’t have time for the people, we don’t have room for the people. We just want the commercial good, but we don’t want to look after the social or cultural good, which is fundamental.

DP: There’s close enough to 18 million people in Tokyo now and 12 million of them commute, which is why it’s such a nightmare. We don’t want to have that. We want to actually reinvent this area. We are certainly not going to impact on parks and things. In fact we want to build some more. The notion of a design alliance is really important to us.

SC: We are on board.

DP: Good.

SC: I think you’ve fleshed out what your organisation’s connection to the Government Architect’s Office is and I think that’s fantastic. I also think it’s good that Peter Poulet has positioned the Government Architect in this strategic role and this design thinking role and design excellence role. I think that’s how we can help, particularly through the Government Architect. Let government experience the best value. There’s a cost for a project, but there is also the value of a project. The value has other things, like social aspects and cultural aspects. You ask every Sydneysider, particularly young men or women travelling, you don’t really think about your connection to your own place until you’re in another place and it’s that idea of ‘you’ve got to leave the land to see the shore’.

You go away and you realise how wonderful you have it here. With every building that I’m involved in designing you feel that responsibility to the next generation when they’re abroad and looking back at their home place. It’s incumbent upon us all to make it that place that they want to wax lyrical about in the pubs of London or the bars in Berlin or wherever.

DP: There is a saying I came across recently: ‘the world is a book and if you’re not travelling you’re only reading one page’. That’s the problem for us. So many people in Australia still think of other parts of the world as just holiday sites, but it’s really important to be able to go and see the great examples of the new and the old and how it all can be made to work together. That’s what we really need to come up with. It doesn’t have to all be new. We can also put really new things next to really old things and it can all be major work.

SC: I think London is becoming a great example of this – and New York City too to some extent as well. You see a really old building next to something startling and new. One highlights the other, like the Power Station for example. Such a strong form, it reminds us of how close and small Sydney was then when our power was generated out of our own harbour.

To have that as a form physically there and being re-purposed and reused for something. I imagine that’ll be part of your development. There’ll be some great new buildings in around that.

DP: That’s a fascinating challenge and opportunity actually. Align something really spectacularly new against that old landscape, or building scape, but the space is there to do it and I’m hopeful we’ll get some magic ideas for how to do that. We’ve got lots of ideas of our own in respect to what’s possible. What’s really important also, and I have a personal view about this, is that you align your assets in the most powerful way. The Government Architect’s office has the most amazing historical detail in relation to design and if you look at the designs they’ve got of the Power Station, it’s fascinating.

SC: I think just about every university every year, there are at least five students doing that Power Station.

DP: I think that’s right. Aligning, in fact maybe even relocating, the Government Architect’s role to be with UrbanGrowth NSW or within the Greater Sydney Commission perhaps or within the Department of Planning is a much, much better location for it because it needs to be a driver of thought and ideas and certainly it can be a driver of innovation. I see the Government Architect’s role as the stoker of innovation. Encouraging new ideas, for example, to use the air space above historic buildings. Using historic buildings and what could be the space below them, for a whole range of things and new offerings. That’s why I think with someone like Peter Poulet, who is so committed passionately to architectural outcomes of great standing, there is a possibility of an alliance, not only mutual in your organisation and mine. I’m not suggesting here a circumstance where you can never say anything against each other’s position, or we are going to expect that we’ll agree on absolutely everything.

What I want to do is to build an alliance so that people understand what we are trying to get at and how you and your members might be able to help us do what we want to do, gain fantastic commercial outcomes, but also design credence. We are lucky enough to have the platform to do this in The Bays and Central to Eveleigh.

SC: Just one last thing, in terms of that conversation between architects and UrbanGrowth. I think the architecture industry is a mature industry and I think it’s helpful that architects and architecture provide UrbanGrowth with frank and fearless advice because that will help you get the best value and the best outcome. I think you can agree to disagree respectfully. We might disagree on 5% to 15%, but that 80% to 85% that we agree on, we should all just muck in and get on with it.

DP: I guess there’s a plea involved in this from me to your members: please don’t come to us with demands for the design competition and the one winner and the one builder. We want massive contributions and the design competition is not a great way to do it anymore. We want to think about what we actually want before we start designing it.

SC: Fine grain, many authors, lots of variation in buildings, makes good cities.

DP: Different architects, different builders, maybe even working on the same building, different elements of it. The Westfield development in Milan, for example. I never thought you’d hear of a Westfield being developed in Milan, but if you look at the three elements of it, you have three different designs, three different architects, three different builders and fantastically different outcomes. It’s an example of how it can be done in a massively historic and heritage-based city.

SC: Next question. What is the potential for the integration of transport and infrastructure planning with land use planning?

DP: It’s fundamental and our recommendation in The Bays Precinct transformation plan is that there must be a total Bays Precinct transport and mobility plan that we develop in a partnership between Transport for NSW, Roads & Maritime Services and us, and including Ports as well. That would be transport-led but UrbanGrowth NSW-managed and the reason we want to do that is because we have to take a long-term view. The need to have a rational approach to this is fundamental.

You’ve got to come up with a plan. There’s no point in building a mass transit solution from Wynyard to White Bay. It’s got to go all the way up through Homebush and out to Parramatta and out to the west. We’re looking 10 to 12 years in relation to such a provision. We do need to come up with some interim stuff and that may be a different light rail usage which would service the Power Station and the Balmain peninsula. We’ve got to be very careful about this.

SC: There’s a railway line going directly to Parramatta.

DP: There is, the western line.

In Central to Eveleigh the transport’s already done, no question about that. The advent of the George Street and south-east light rail should be much better utilised in its trajectory, and there are other elements that need to be thought about.

Fundamentally it’s about changing the transport priorities to conform to the inverted pyramid, and the top of that is walking. You start to think about how people can walk to The Bays at the same time as you start thinking about the mass transit.

SC: That does seem like an integration of developing the idea of the land use at the same time as the transport use, not in separate silos.

DP: Yes, and you give people different ways to do things. Our aim is to develop The Bays as a seven minute precinct. In other words, you can get somewhere or get to some form of transport that will get you where you want to go within seven minutes. Now I’m not saying that you can walk from White Bay Power Station to the CBD in seven minutes, but you can get a form of transport that will get you there in seven minutes, whether you ride your bike or whether you catch a ferry or whatever. You can get to that device within seven minutes, and not take another 20 minutes to get you there. You can make your journey effective within seven minutes.

The only way you can do that is to have a very integrated approach. The word integrate is much maligned here. This is where the Greater Sydney Commission hopefully will make such a significant difference. The question of whether transport should drive the planning or planning should drive the transport is fundamental to New South Wales and inevitably in this city, the planning is going to drive the transport.

SC: One services the other.

DP: One services the other. That’s why we’re taking this approach at The Bays. We’re looking to what the destinations are before we start to do the transport planning.

SC: How do you see UrbanGrowth NSW’s relationship with the Greater Sydney Commission and how do you see the Greater Sydney Commission operating?

DP: We’re determined to be an aligned contributor, but to be honest we don’t know exactly what it’s going to do and it appears that level of knowledge is not apparent anyway.

SC: Sydney is this great big organism. We’re bounded by a national park up north, a national park in the south, the national park and the ranges to the west and the ocean to the east. I guess we need to think about all that landmass in there very carefully. We can knit all that fabric together in a careful considered way. If we have all these disparate bodies that aren’t necessarily in that great, coherent conversation, we might miss that opportunity or kick it down the road a bit further.

DP: I think ‘kick down the road’ is an issue for us because there is a tendency to leave things as they are. One, because it’s easy and two, it’s certainly much cheaper. There’s is a view in the minds particularly of older Sydneysiders, that this is my patch, this is my place, not yours. Your driveway and your house might be yours, but the rest of it is ours. We need to have a fundamentally different approach to it.

SC: In January, my predecessor Joe Agius wrote to you proposing principles for the redevelopment of the Bays Precinct site. What is your view of his proposals? Are there any areas of disagreement?

DP: Joe and I sat down after the last day of the international summit last November, which he attended for the whole three days.

SC: He spoke very highly of that.

DP: Yes, he made a great contribution. He was there for every single second of it and we sat down afterwards and he said some nice things about how important it was, but he said there was a dawning in his mind about how important it was for your profession because for the first time we brought people from overseas with the experience and the skills and the ideas and in a way that didn’t portray Australians as being lesser mortals either mentally or professionally, but to learn from a bunch of people who’ve been through a whole different range of things and the sort of gelling in his mind was that there’s much to learn.

He asked me how best to go about forming the alliance that we’re talking about today and I said: ‘Well, the best way would be to tell us how you see this happening’. See what our key principles are. That’s what came out of the first summit and there’s a great alignment between what Joe’s written and what your members have contributed.

The fundamental elements here are funding and finance. You need to work out what you’re going to do and how you’re going to fund it before you start. It’s crucial. The planning imperatives, the public access, invite many players, all of what we’ve talked about already. The diversity of housing is crucial. This term affordable housing is problematic. I’m trying to replace it with ‘diversity in housing’ as opposed to ‘affordable housing’.

SC: It gets confused with housing affordability and they’re two entirely different things.

DP: Two different things entirely.

SC: A third of our society qualifies for affordable housing. There’s a real conversation we need to have in Sydney about the cost of housing, so two entirely different things.

DP: Two entirely different things. That’s within the planning imperatives here. I think that needs to be fleshed out. I wouldn’t use the word ‘corrected’, ‘interpreted’ would be a better word. We all of us know that there’s two different elements that we need to deal with. Well, at least two different elements, but certainly two important differences there.

SC: It almost needs to be a keyword for accommodation or keyword for housing rather than ‘affordable’ housing.

DP: That’s it as well, but smaller and smarter use of spaces in buildings. When you’ve got massive voids in buildings that are caused by lift wells and stair wells that are badly designed and all that stuff, you could use them for a whole range of things, and so we need to maximise the use of that.

Diversity is also about great things, great opportunities for people to do things that are different. I saw when I lived in London particularly young, smart, professional people. They don’t want to live where we used to live or we would want to live. They don’t want to have a 40 square apartment. They’re quite happy with 15 squares as long as it’s great design.

SC: It’s quality over quantity, isn’t it?

DP: This is the diversity that we need to bring about. Transport, we’re absolutely at one with that. Joe’s written here: ‘Light rail or metro’. My view is both. More buses, rapid transit bus, use Glebe Island Bridge – you know what opportunities that opens up? For example, in Berlin you see people walking straight across the light rail or the tramway as they call it. It works. People in Melbourne have been living with trams for 130 years. It works. People get used to them.

SC: That’s why people love Melbourne, don’t they? I think you hit the nail on the head. It’s about everything, but particularly when we think about transport or housing types or building types, you said the word ‘diversity’. I live at Dulwich Hill, there’s the light rail using the old railway line. That makes sense. Putting a light rail down the road where it’s going to be affected by the same traffic problems as roads like lights and crossings doesn’t make sense. And then the idea of the metro. When you think of all the great places in the world, London, New York, Barcelona, Tokyo, they all have metro. You don’t have to worry about a timetable, you turn up and within five minutes you get a train somewhere.

DP: I don’t think in six years in London I could have waited for transport for more than 10 minutes ever.

SC: In Sydney you can wait half an hour.

DP: There are other elements of diversity as well. If you look at the Western Harbour from Johnstons Bay, which is the head of The Bays, why aren’t there ferries in there? Why wouldn’t you have a ferry that goes to the fish market? You should. They’re not mass transit solutions, but if you use a Manly sized ferry you can provide some serious amenity for people. Then that also provides more customers for the market district. Whatever goes in at White Bay, if you have an effective ferry system you’re providing amenity for the people who live in that area.

Take the Berlin Wall of the 10 foot fence down and let them actually get into the space, which we did on the Discovery Day. The other thing that we need to think about in terms of diversity is that light rail doesn’t only deliver a light rail solution. If it’s designed correctly like in Holland, you can have a light rail that’s got a two lane bike path each way. So you’ve got three to four forms of transport in the one pathway. We need to be much, much smarter about the way we do that.

In terms of sustainability, I call it resilience because resilience is a much more powerful proposition for me because it is building cities that are resilient economically, environmentally, socially, and in terms of liveability and being able to sustain and resist, being much more capable and resilient in weathering a 2008 type level of financial crisis. How do we do that? We make the city much more achievable in terms of its economic platform by bringing a whole different bunch of people who will do different things, as I said before.

Resilience for us is going to be the driver. It goes way beyond sustainability. We’ll be looking at what needs to be done according to the usual sustainable practice, but being more innovative, for example, geothermal heating, water cooling, different ways to treat waste. My own aim is to have an energy production capability through the geothermal stuff where we actually export energy from The Bays Precinct to the sub-region rather than the other way round.

SC: People will go to The Bays Precinct because they identify with it. It’s smart, it’s compact, it’s fine grained, it’s clever, it’s innovative, all those things. People will buy into that because they identify their own principles with those spaces.

DP: People will come there hopefully because we’re doing things that have never been done in the world before or are of world standard. This is where we want to be and also we need to go way past sustainability. Sustainability’s become in many ways a compliance regime, where you’ve got to be five, six star. The reasons for your being six star are no longer the focus, you just need to get the qualification. I see dangers in that because it sets a level where people no longer have to aspire to be better than six. Once you get to six, that’s okay.

SC: It’s a human trait, isn’t it? That’s it. I’ve arrived.

DP: I remember when I was the CEO of the City of Melbourne we built Council House 2 and that was then the first 6 star Green Star office building in Australia.

SC: I went down there specifically to see that building.

DP: It’s a magic place, isn’t it? When we built it, we wanted to send the signal to the rest of Australia and to the rest of the world that you can do it if you’re prepared to pay premium. You get it back. We were battered from pillar to post, Rob Adams and I, about why should we do it.

Now there are I think seven 6 star Green Star buildings in Melbourne. The reason I tell you this is that that’s the sort of stuff that we want to do in The Bays. We may not even know what we want to do yet. But anything that’s built there, they can’t be less than six stars in my view. Why would you? Why would you settle for a four star rated building in the most high profile urban renewal site in the world? The answer is: you shouldn’t. That goes to the design.

SC: One more question about the time scale. You’ve got this big site and by necessity, that’s going to take a long time to come to fruition. I guess there are two aspects – the strategic vision, what it’s going to look like and I guess that’s also a part of the Call for Great Ideas. Then the other aspect is, once you collect those ideas and you start developing plans, the implementation and I guess that’s put in the backdrop of the political necessity of Premiers who like to turn up having the shovel in the ground, turning the dirt. So I imagine there’s that pressure coming from the side.

DP: There is, although we’ve been able to withstand that by explaining that the reality here is that whatever we do must be transparent, public and appropriate. The Call for Great Ideas and the planning process that we’re going through is to flesh out some really great ideas. Not all of them will be great, but we might just come up with three or four wonderful nuggets of how we go about it.

We’ve been able to generate so much interest publicly about it and within the bureaucracy. There are some that may not share that level of support.

The reality is, we’re not going to go to the inclusive route to the point where we’re going to try to get 100% agreement. We’re going to settle for what’s an appropriate level of agreement.

SC: Most of the people, most of the time.

DP: Most of the people, most of the time. We’re never going to please all of them. 80% would be good enough for us, because 100% would mean we’ll fail. The enemy of good is perfect. We don’t want to be perfect, but we want to seriously be good and so what we want to do is to aim at those processes that enable us to develop things that work, that are great to look at, to live in and be part of and which transform the city. The shovel-ready project is an issue for us. The Premier’s view is that he’d love to see us get started, but the reality is when you start out on a project as big as The Bays or Central to Eveleigh you need the time to do it properly.

People say The Bays is the biggest thing since the Olympics. It’s going to be way bigger than the Olympics, because what we are doing is building Sydney’s next 100 years. We built it, we ran it, it was the best Olympics at the time and we’ve been struggling like hell from there on to make it relevant. This is where the lesson has been learned strongly in London, with 60% of the venues being temporary and a different way of approaching the whole event.

That’s the sort of thing that we need to do here.