table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

Space to Play

The collaborations between Philip Coxall (McGregor Coxall) and John Choi (Chrofi) have set a new standard for parks in Sydney. Shaun Carter met with them to discuss their agenda-setting approach to community leisure spaces.

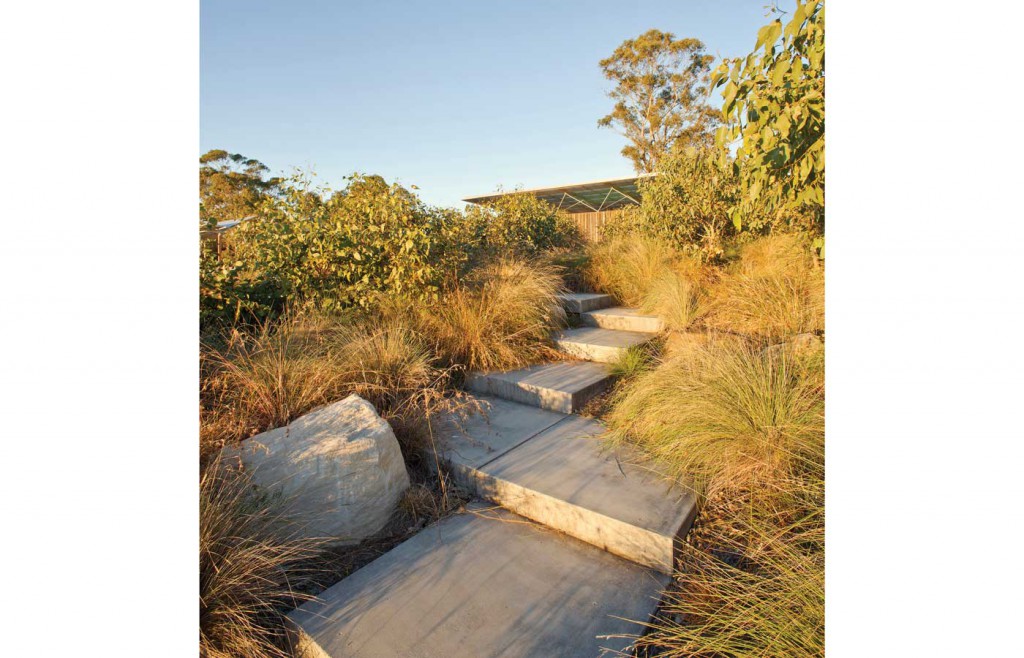

Shaun Carter: You guys have done a lot of work together. My great reference point for that work is Ballast Point Park. Your collaboration there reminded me of all my childhood adventures playing in the bush and in creeks. Suddenly, there was something a bit wild about it – there was topography, there was texture and there was materiality. You were making walls that were reading the topography of the land and bending and folding those walls around. My daughter got there and straightaway she rolled down the hill and then she said, “Come on, Mum and Dad. Let’s all do it.”

Philip Coxall: Let me tell you the interesting story behind that. That’s exactly what the grass knoll was designed for. They came asking for a play area up there. I said, “The whole park is a play area, but I’ll give you one little dedicated play area.” I always remember as a little kid rolling down the hill. Do you know what happened? They laid it two weeks before the opening and so the grass didn’t bite. [When it opened] first kid that arrived and the first thing they did was roll down the hill. By the end of the day, the grass had worn down.

It’s still there, by the way, but they hadn’t been able to maintain it because they can’t get the people off the grass to get it back to where it should be.

SC: It’s almost too successful! For a city park it is really interpretive. You left elements of where the tanks were and you’ve got the wind turbines. You walk on things that were remnants – I thought it was an extraordinary interpretation and that beautiful piece of architecture that was the bathrooms.

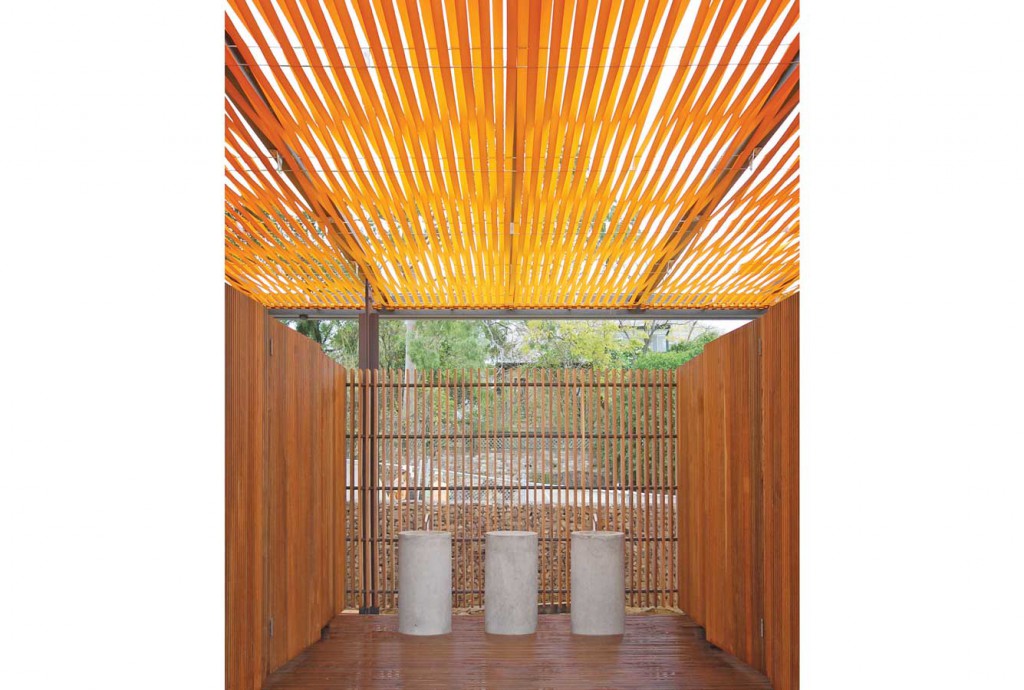

PC: We worked very closely together on Ballast Point Park and we went away one weekend to work on it. John had this idea over the weekend which brought in this floating canopy. We were looking at how we could put something in there (that was) recycled. That was our tenant for everything. We had to recycle everything so anything we touched had to be recycled. I kept on thinking it was sticks or twigs and then John came in, and he laid it out the canopy, it was one of those moments where you look at it and you just go, “You had me at hello.” He goes, “And guess what? They’re recycled seatbelt straps that had failed the safety test. Then it all comes together because (of) the stripes. They originally said they wanted [Antoni] Gaudi. Remember that?

John Choi: They wanted the toilets to be Gaudi-esque. I’m fascinated by the process. Various people in the community express what they want through precedents and aspirational words. I think the great value of the profession is to be able to translate these spoken and unspoken desires into something tangible. We help people decide what they want by showing them what’s possible.

The future is a difficult business, particularly when you are proposing something quite different from the norm. To some people it never becomes tangible until it gets built. That was the case with Ballast Point. No matter what we showed and said, many people had the image of a [simple] green park with trees.

Afterwards the same people that were very cautious or had other thoughts of what it needed to be … Some of those community members came up to you afterwards saying, “Look. In essence, we didn’t know what we wanted.” I think when you design something that’s a small iteration of what currently exists in the world, then it’s easy for people to imagine a slightly different version of that, a prettier version or different stylistic version. Lot harder with larger leaps.

SC: It’s the great leap of faith. Isn’t it?

JC: I guess it’s in making those aspirations and possibilities tangible enough that decision makers, whether it’s the community or elected people on behalf of the community, can make decisions.

There’s a good opportunity for the profession to imagine how we can add value in today’s context, but you need to make greater leaps to have things like the Highline or Thomas Heatherwick’s Garden Bridge. These examples, where either the designer or a community group imagine a different kind of experience you can have in the world. And then somehow finding a way to bring it to reality, and then once something is deemed successful every city wants a version of it.

SC: I would imagine you’ve probably heard a couple of times, “Guys, let’s do a Highline.”

PC: Yeah. That’s right.

JC: Which brings me to Parramatta and Western Sydney. You are obviously doing something that is different and new, and that city makers want you to be involved in their projects.

PC: It’s an interesting thing. Out of all the work that we have done collectively, the most successful in terms of generating more work is Pimelea Parklands [Western City Parklands].

JC: The design takes the traditional model of the open space barbecue, shade structure, bush-type scenario and cleans it up, putting it in a framework that is easy to respond to. All the councillors from various councils go out and have a look at it. When they see it they say, “Oh, we want one of those.” We get quite a lot of calls on that. I don’t think I’ve ever got a call on Ballast Point Park.

SC: What is it do you think they seeing in that park that makes them want to have one of their own?

PC: It’s beautifully constructed and designed. It’s not too confrontational, not too radical or out there. Ballast Point Park can challenge you a little bit.

JC: Pimelea is a softer form of place-making. How there is natural fostering of certain kind of activities – it’s more a non-physical design – functions that are curated and partly shaped by the physical space, but also by the arrangement of it all. Providing the larger activity, the small activity, more active/passive, and that naturally…

SC: …Gives space between things.

JC: I think if I look at the way architecture is evolving, it’s increasingly having a broader understanding of all those nonphysical aspects of what creates an experience. How people understand, enjoy and interact, all those things are equally important … and these can define a place independent of the physical design. That’s why I think we enjoy collaborating with landscape architects.

We’re coming across new opportunities in terms of how society interacts with a park. The built structure around leisure and experience economy isn’t really that evolved. It’s a reasonably recent sort of pattern. So there’s lots of opportunity to imagine new kind of experiences.

SC: One of the things that jumps out for me when we talk about these things is risk. I see two different risks. There is this fear of the unknown in the conceptualising for government and councils. There is the experience of risk when interacting with the park – the excitement that comes with jumping off a rock or going through that culvert or rolling down that hill. All those things are things that made these great childhood memories.

PC: I think that’s beautifully said. In fact, one of the nicest compliments as well. That’s in essence what it’s about – when you go to a place and you have to have an imagination. You’re crawling through a culvert, but you’re not really crawling through a culvert. You are challenging yourself.

JC: It’s a tunnel. It’s makeshift. There is water. There is noise, cold.

PC: Co-creating – that you are making those excellent, important memories for childhoods rather than the bland pastiche of going through a plastic playground. How is that in any way, shape or form something that’s going to really embed you and start you thinking in a different way other than “I got it done and it’s over”?

SC: I think those experiences increase self-esteem and they allow children to judge risk and in adult life that’s an important factor. There is greater social and cultural benefits of having things that are more experiential, more challenging.

It’s fascinating and if we think about risk on that other side so governments or councils or groups of people that want something different or they’re really tantalised by the prospects, but just in this conservative time not necessarily allowing themselves to take that leap, even to engage you guys to do concepts for them.

JC: No risk no gain. If you want to be a leading city, you have to lead. It’s going beyond mimicking ‘best practice’ and having the collective confidence to take the leap and inspire with new possibilities.

For me, all this is a move away from defining architects or landscape architects as designers of just physical things. More and more, [we should be] defining the profession as designing relational structures. Expanding our traditional role of arranging materials in space to also arranging nonphysical relationships which collectively shape & define places, economy and identity.