table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

In the Shade

Nick Wood, founder of UK practice How About Studio, is the third recipient of the DROGA residency. He spoke to Mark Szczerbicki about his research into the Australian awning

Mark Szczerbicki: What led you to applying for the Droga Residency in Sydney?

Nick Wood: My application to the Droga Residency was a continuation of my recent studies on the regeneration of London’s High Streets, supported by the Mayors Outer London Fund. I had visited Sydney in 2013 and had been captivated by the awnings as an element of street architecture that we do not have in the UK. I started to consider the potential of what these structures could be, and this formed the core of my proposal.

MS: How did you perceive the general attitude of the local planning bodies to awnings and awning design prior to your arrival here? What you found, did it match your expectations?

NW: Before my arrival I was able to explore various online and historical resources regarding Sydney’s awnings. The articles I initially uncovered showed the awning as an element that had not undergone significant review in recent years beyond that of its structural integrity.

On arrival I was slightly surprised to find the lack of conversations that were being had about the awning. Local practitioners, policy makers and public all agreed on its necessity for the Australian climate, and there was a fascination with its heritage, but it seemed perhaps overlooked as an active element of the street. Current awning legislation, such as the City of Sydney Awnings Policy 2000, is aimed at providing maximum coverage in relation to pavement width, and its main reference to its neighbour exists as a maximum step height.

MS: Can you comment on the element of making in your research I was particularly impressed with your idea for the mirrortop trolley, which was like a miniature piece of architecture in itself, and allowed for a new way of engaging with awnings…

NW: Perhaps as designers we take our ability to imagine ideas and spaces for granted, but it is the way we decide to communicate these to clients and users that is key. Making objects and prototypes to aid these discussions creates a transparency and establishes a relationship.

Within my research I have presented the awning as a third architecture that alongside buildings and landscape can make an invaluable contribution to the human scale experience of the street. The mirror trolley was developed as a practical way of engaging the public with conversations about the awnings on the street, as well as a way of me exploring ideas of the awning as journey.

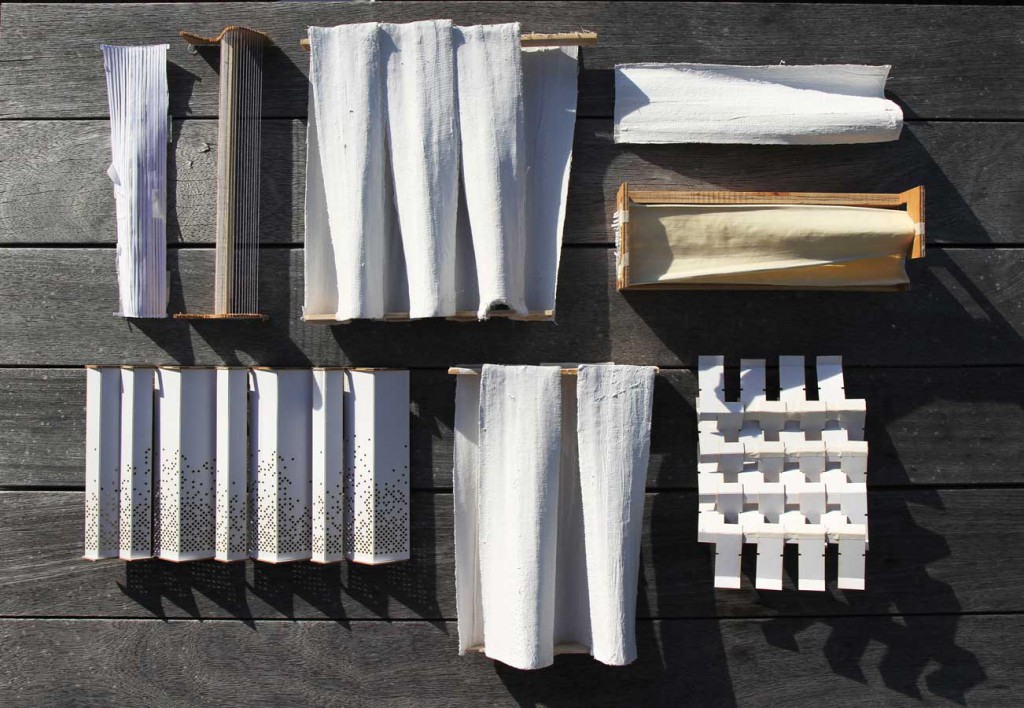

I think 1:1 making plays a key role in my design process because of its focus on the human scale. I also like to embrace the expressive object in preference of the glossy images in the formative stages of a project.

MS: I understand that you looked at the Marrickville area during your time here. Why was this part of Sydney particularly suitable to your research?

NW: I began my explorations in Sydney by foot, keen to explore its [the awining] changing condition across different parts of the city. In the first week I walked from the city centre to Redfern and then continued down King Street to Marrickville.

Marrickville already has a traffic-calming setup, where they have reduced the size of the road and increased the space for cafes and businesses, which has started to include urban gardens and hedges. I think that these street-level changes are going to be happening more and more throughout Sydney as people see the importance of bringing human scale back.

I chose a context [Marrickville] where the street situation was looking reasonably healthy, and to be in an area where you’ve got, as far as awning telling the story of a local area, a very diverse mix of light industrial, natural areas, and some residential areas. So I felt that Marrickville, as a place, could represent the character of a lot of different parts of Sydney.

MS: What are some of the ways that awnings can contribute better towards the leisurely enjoyment of our streets, beyond the simple functions of protection from weather or nighttime lighting?

NW: Awnings can get swallowed up by a conversation about café culture and thinking about consumers. While there is an idea about having these public spaces to go and meet people, there’s also a need to provide private spaces and private moments within the street – so if people perhaps don’t have a private space in the home they can find one of their own in the city. Benches line the retail streets of Sydney to provide a place to rest, but the awning can create unique moments to want to stop and just enjoy sitting there…

During my residency there were a number of street festivals – popular amongst residents, these were celebrations of local culture. With small design adaptations awnings could support these events by providing something to which they could literally “plugin”. The idea that you could create rows of power points opens interesting opportunities, like a pop-up use.

I think there is a general opinion amongst the public that aside from a need to upgrade the finish of the awning, as an element of the street experience it performs well in shielding pedestrians from the strong Australian sun. The first step is therefore to engage the community in its potential beyond this, which could perhaps start with a reminder that each awning is unique in its location and relationship to the sun.

MS: There have recently been a number of proposals and visons for the improvement of Sydney’s streets, in which everyone’s thinking about the street surface. Awnings seem to be a forgotten player and a missed opportunity in the rush to make our streets better…

NW: I guess the reason for that is that there is a kind of ownership by councils of the streetscape, and their ability to overview and control the pavement, but awnings are still individually owned by the building owner. There are a lot of requirements placed on the private owner by the council, but not so much in the way of lighting or continuity. It is a pity that owners just want to do something low-maintenance that will last a long time…

I think this is one of my key findings – not treating the awning as a building, where it becomes cantilevered and almost seamlessly attached to its host, and loses status as a temporary structure. If you look at awnings in historical photos they come across as temporary, very different to the buildings behind them, and I think there needs to be more of an openness to adapting awnings to their immediate situation underneath.

MS: How are you planning to collate the results of your research, and what would be the next step in realising the potential of some of your ideas?

NW: I am currently collating my research into a publication which will highlight some of the key findings and questions as well as recording the design and build of the 1:1 awning prototype with students from UTS and UNSW. No one argues that the awning shouldn’t be there due to their incredible amenity and protection, so they always will be part of the street in Sydney and the Australian culture. There were some moments during my residency where I would step back and think ‘Well this would never happen anywhere else in the world…” However, the next step lies in the hands of some ambitious developers or landowners to commission awning designs that begin to question the existing regulations using high quality design, but ultimately I think the guidance provided to designers of awnings needs to be reviewed to align with identified future potential.