table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

Regional Practice

As Chair of the Institute’s NSW Country Division, Sarah Aldridge is acutely aware of the challenges that the profession faces in the regions. She takes a look at how the figures stack up and where the opportunities for engagement may lie.

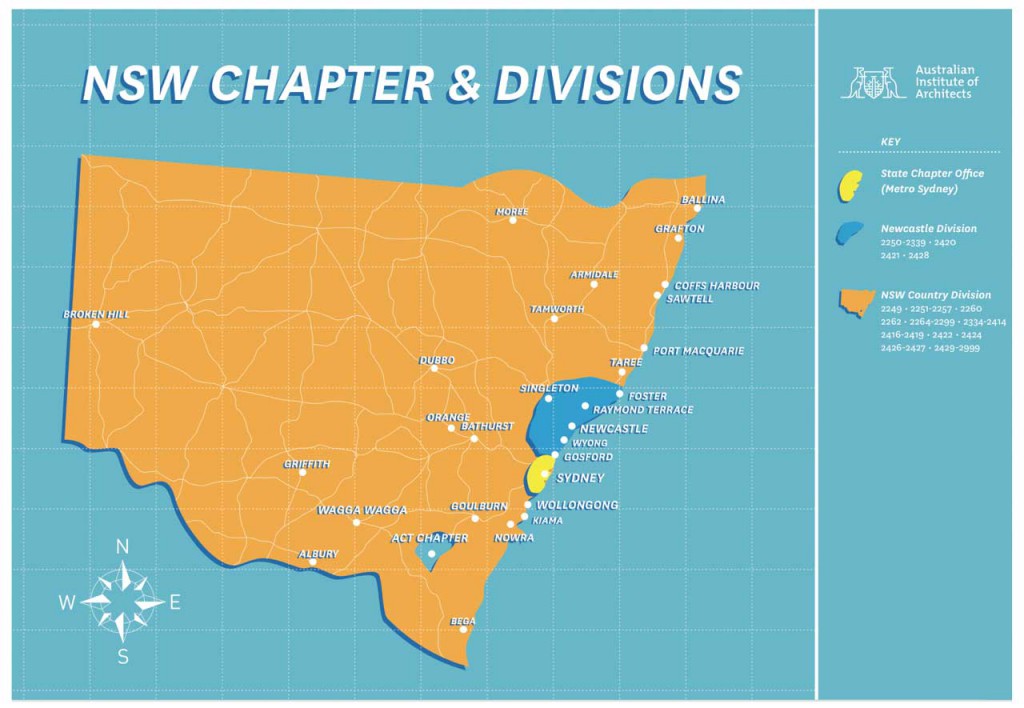

Approximately 20% of NSW members’ practices are located outside the metropolitan area of Sydney. Of that 20%, approximately 10% operate in the Newcastle and Central Coast areas with the remaining 10% scattered across the rest of the state1. These figures reveal the very small number of practices that do not rely on work in Sydney or Newcastle for their living. This small minority faces an array of challenges when it comes to finding work and public perception of the profession.

So how do we raise awareness in regional areas about the value of architecture to the built environment with a limited or non-existent architectural presence? The low number of architects practising in regional areas – particularly west of the dividing range – is partly symptomatic of the general difficulty in attracting professionals to inland rural communities, but is also related to a lack of sustainable workload. It is unsurprising then that many regional practitioners are found in clusters along the east coast where the larger population centres and stable employment are located.

COST VS QUALITY

In areas where there is the desire to engage an architect, there are still significant economic factors at play. With the high costs of land and construction relative to the market value of a completed development, the spotlight often falls on architects’ fees as a potential area of cost saving. And rather than looking to shave a bit off the cost of the fees, the service is often cut altogether where there is no mandated requirement for the use of an architect. With tight budgets and little appreciation for good design in regional areas, engaging an architect is a low priority for most. Changing this perception is important because it results in a reduction in potential workload and a subsequent decrease in the quality of the built environment.

In a recent lecture at Bond University architect Kerstin Thompson suggested that on domestic projects where the costs associated with using an architect cannot be sustained, the architect could concentrate on the relationship between building and street and the wider context, and not get involved in the interior design where so much of an architect’s time and fee is spent. By reducing the architect’s scope and fees in this way, the service of an architect becomes more attainable to a larger proportion of the community, thus raising the impact of architects on the built environment.

EMPLOYING LOCALLY

Bearing in mind the lack of regional universities offering architectural education, all regional practitioners have studied, and often lived and worked, in cities across Australia and abroad. It is strange therefore that the perception of regional practitioners as being low-skilled and unable to deliver complex projects, often persists. The use of city architects for many regional projects endangers the viability of regional architects. If all the high budget, high profile projects are the domain of city architects, what future is there for regional architects? Of course the small size of most regional practices restricts their production capacity, but in collaboration with a larger city practice the regional practice is of huge benefit to a project. The involvement of a local architect, with the advantage of local knowledge and geographical proximity, on all regional projects would go a long way to providing a core workload for regional practitioners.

So apart from practice size, what are the barriers to regional practices winning these prime commissions? To be able to tender for public works, however modest, practices are often required to hold $20 million of PI insurance, have formal QA certification and written OH&S documents, and have experience of working for a public body on projects of a similar nature. Most regional practices are unable to fulfil these criteria, even though they may be capable of doing the work. The BER schools program enabled regional practices to deliver high quality buildings within strict budget and program constraints without being precluded from this work by the restrictions imposed for public works. While the BER scheme attracted plenty of criticism, this was largely directed at the project management fees for public schools, not the architects of the independent school projects or the buildings they delivered.

But why is it important to retain and nurture the presence of regional architects? According to a recent article by Matt Wade in the Sydney Morning Herald more than two thirds of Australia’s population lives in one of the seven major cities, with more than 40% living in either Sydney or Melbourne2. Compare this to Japan where according to IMF figures less than 10% of the population lives in the two major cities or England where the figure is less than 20%, and you realise how urbanised Australia is. With population figures continuing to rise, how long before our major cities become unsustainable and we look to our regions for a solution?

Acccording to predictions by Deloitte Access Economics, population growth in many areas in regional NSW is predicted to be 1% per annum for the next 15 years (compared to 1.6% for Sydney), resulting in significant expansion of our regional towns and cities3. In addition to predicted population growth, expanding opportunities for remote working made possible by developments in technology, mean regional populations are only going to increase. Unless we want homogenised expansion that results in every main street looking the same we need to understand and protect local character. We need development that is appropriate to its location and community, taking into account the climate, natural environment, culture, heritage (both Indigenous and European), transport needs, and economy. Of course such communities can benefit hugely from input from metropolitan practices, but this cannot be at the expense of the localness of the place and its people. Regional architects have a key role to play in this process.

INSTITUTE INITIATIVES

So what are we doing as an Institute to address some of the issues affecting regional architects? The Division has established a Special Projects grant program to fund initiatives by regional members that promote the value of architecture to the community4. Country Division runs seminars and workshops across the state throughout the year on topics of regional interest, often in conjunction with a free public event such as Architecture on Show or a public exhibition. This kind of grass roots advocacy helps raise awareness of architects and the positive impact they can have on communities. Country Division also runs an awards program, the entries for which are exhibited online and around the state to the public. The awards categories are tailored to respond to the type of work being carried out by regional practices, for example promoting low cost housing with an award for project under $350,000 and the Vision Award for visionary projects that push the boundaries of regional architecture. To address the issue of regional employment Country Division is in the process of establishing a graduate placement scheme designed to link graduates looking for work with regional practices struggling with recruitment.

THE FUTURE

But is this enough? Other professions seem to be able to attract significant government funding to encourage employment in regional and rural areas. The Department of Health offers the General Practice Rural Incentive Program where GP’s working in regional areas are paid an annual incentive of up to $60,000, depending on the location of their practice. Should the Institute, as part of its new focus on advocacy, be seeking a similar scheme for architects?

In August of this year the NSW government launched Jobs for NSW an initiative to direct $190m of funds to areas of NSW that will provide the greatest economic impact in terms of job creation. A minimum of 30% of this fund will be directed to regional areas. Surely this is something that we need to be involved with to ensure that some of these funds are directed towards architects and job creation in the construction industry? It is clear that regional practice will be crucial to the necessary expansion of our regional economy. We just need to make sure that we do a good enough job that our future regional towns do not inspire another volume of Robyn Boyd’s The Australian Ugliness.

Sarah Aldridge

Director, SPACEstudio

Chair, NSW Country Division Committee,

Australian Institute of Architects

FOOTNOTES

- Based on AIA NSW memberships figures from November 2015.

- The problem with Sydney and Melbourne, they’re just too big, Matt Wade, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 November 2015.

- Deloitte Access Economics 2012, The NSW Economy in 2031-32, Report to Infrastructure NSW.

- Details of this year’s grant recipients can be found on the Institute’s website: architecture.com.au/events/state-territory/newcastle-country-division-events-awards