table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

- Recycled plasterboard and metal framing studs in the opening rooms of Alejandro Aravena’s Reporting from the Front

Curated by Alejandro Aravena 28 May – 27 November 2016

For the last two years, Alejandro Aravena had been stockpiling discarded material from Rem Koolhaas’s previous edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale. As this year’s curator and 2016 Pritzker winner, he recycled plasterboard and metal framing studs for his statement in the opening rooms of this year’s show, Reporting from the Front. Highlighting the vast amount of waste that shows like this generate, the Chilean architect reminds us we are complicit in architecture’s wastefulness.

Whereas Koolhaas insisted on two full years to curate the exhibition, Aravena had a mere ten months to assemble this show. And while Rem asserted architecture alone is not capable of filling the Arsenale’s vast space and collaborated with dance, music and film biennales to do so, Aravena in this 15th edition of the Architecture Biennale reverts to the ambitious proposition of occupying the entire space with content. Filling both the Arsenale and Central Pavilion with a vast catalogue of upcycled, recycled, low-tech, self-built, community-initiated exhibits – aligned to the social responsibility theme – is a massive undertaking.

There are moments of insightful and focussed exhibits such as Ephemeral Urbanism by Rahul Mehrotra, Felipe Vera and José Mayoral. Investigating a range of scales from temporary megacities to small urban infill, they argue ‘that for cities to be sustainable, they need to be accommodating more temporary fluxes in their structure’. The result of Aravena’s struggle to meaningfully occupy the entire Arsenale, however, is a slightly too granular and exhaustive collection; one is left fatigued by the sheer volume of content, set adrift in the lack curatorial focus.

Moving through the exhibition is a curious reoccurrence of exhibits of thin-walled, compressive structures. In the centre of the Arsenale exhibit are 399 digitally-fabricated limestone blocks, assembled with no mortar by specialist stone masons, by ETH’s Block Research Group’s (in collaboration with Ochsendorf DeJong and Block). The Armadillo Vault seems unthinkably expensive in terms of both effort and cost, particularly when displayed alongside their array of low carbon, low cost vaulted structural experiments.

Another vaulted structure, Foster Lab’s Droneport, sat outside on the water’s edge and Solano Benitez’s Golden Lion-winning brick arch was in the Central Pavilion. Awarded by the jury for ‘structural ingenuity and unskilled labour to bring architecture to underserved communities’, the idea of accessible, low-cost architecture with high-value design appears to have been a tantalising proposition for Aravena. But is this nostalgia for vaults and arches, delivered via a heavy reliance on technology, a viable example for building communities in remote parts of the developing world?

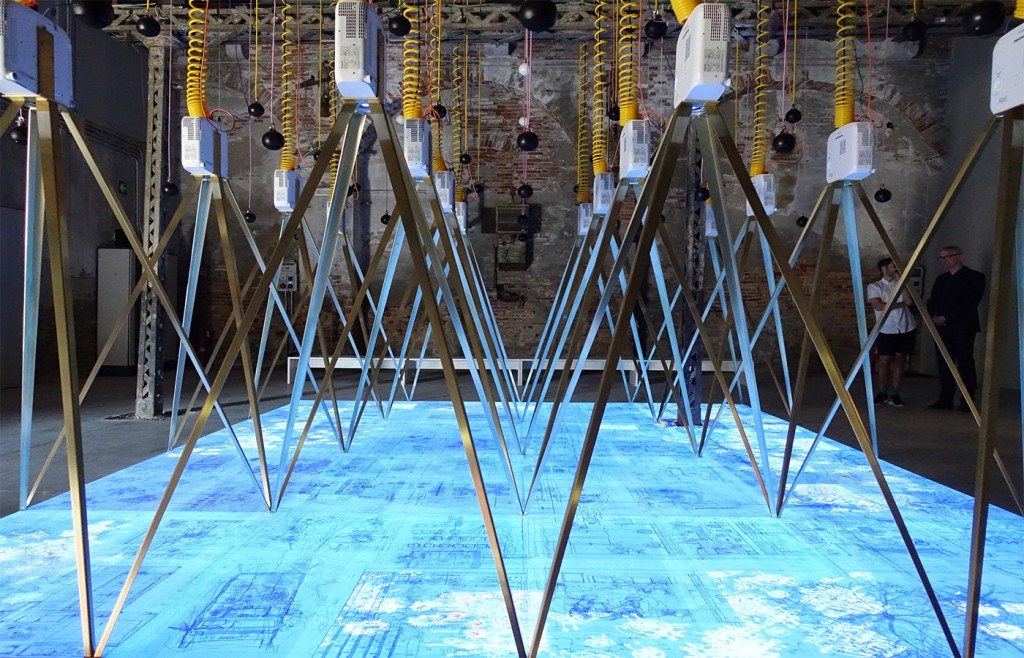

At the end of the Arsenale are several national pavilions, including the Irish pavilion’s installation by Níall McLaughlin Architects. Losing myself comprises 16 downward-facing projectors, mounted on custom-made quadpods, connected with yellow umbilical cords, set amongst a field of 56 speakers. Playing birdsongs, radio news clips and Angelus bells at midday, extensive studies of the Alzheimer’s Respite Centre, designed by McLaughlin some 15 years ago, led to this mesmerising time-based drawing. Projected directly onto the rough concrete floor of the Arsenale, McLaughlin and his team of drafters reimagine how 16 Alzheimer sufferers see that building. It was a thoughtful, site-specific response and a timely palette refresher. Thailand’s pavilion Class of 6.3 exhibits nine schools after the 2014 Chiang Rai earthquakes. It highlights architecture’s important role in the rebuilding communities, while simultaneously creating an opportunity for young offices.

Over at the Giardini, my top pick was the British pavilion. Putting the home back at the ‘frontline of British Architecture’, Home economics explores five new models of domesticity via 1:1 installations, each themed around specific time-based occupations of the home, spanning hours to months to decades.

Also noteworthy was the Japan Pavilion’s reliably thoughtful contribution. Positioning architecture as a potential agent of social change, it addresses problems of inequality and poverty, particularly in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. Real-world design, represented through video, drawings and large-scale models, made this exhibition accessible, engaging and relevant.

‘Large openings were created in walls of Germany’s heritage-listed national pavilion, symbolising the country’s current open-door policy … a willingness to suspend architectural bravissimo for the sake of re-engaging architecture with politics, placing social conscience above design. Yet, this kind of politically correct gesture sparked off heated debate’

Australia’s contribution, The Pool, is the first architecture exhibition in the new DCM-designed pavilion. The refreshingly single-themed installation by Sydney trio Amelia Holliday, Isabelle Toland and Michelle Tabet, comprised of a shallow pool, replete with timber bleachers. This created an ideal scene for nattering by the water’s edge with feet dangling in the cool water.

A common criticism of The Pool was its apparent frivolity against Aravena’s weighty topic. However, the call for entries to the Australian architecture biennale occurs before the main theme is announced. Any response to the overall theme is by chance encounter or by reworking details after the fact. Yet most visitors view the pavilion in the context of the Biennale’s overall focus, unaware that it is detached from the theme. Enabling a more considered response would require the commissioning process to occur after the curator’s call.

Germany takes the elephant out of the room and tackled the pressing issue of the immigration crisis. Large openings were created in walls of their heritage-listed national pavilion, symbolising the country’s current open-door policy. Making Heimat. Germany, Arrival Country is evermore relevant as Brexit ramps up debate around reducing immigration. The pavilion shows a willingness to suspend architectural bravissimo for the sake of re-engaging architecture with politics, placing social conscience above design. Yet, it is this kind of politically correct gesture that sparked off heated debate. Patrik Schumacher, the director of Zaha Hadid Architects, provocatively called for this biennale to be closed, stating: ‘we have to stop what we are working on in our real lives and suddenly become amateur commentators on social processes, which we’re unequipped to comment on’.

Schumacher is right, but only in revealing just how far architecture has drifted from its role as a legitimate agent of social change. Yet rather than closing the door on social processes, Aravena’s Biennale attempts to re-equip the profession with a renewed focus and responsibility, seeing ‘architecture in action as an instrument of social and political life, challenging us to assess the public consequences of private actions at a higher level’.

The headline image of archaeologist Maria Reich perched on a ladder has little relevance as a poster for an architecture exhibition. Aravena’s Biennale dances this line precariously, providing just enough visual stimuli and heady research. In many instances, inconsistent curation of exhibits, further diluted by preacherly slogans, detracts from the rare moments of brilliance in the show. However, Aravena does not seek applause. Rather, he paints a picture of quiet resourcefulness in observation and empowerment by action; for when Reich carries her ladder into the desert, it is only then she can make sense of the significance of stones on the ground, and from this ‘conquers an expanded view’.

Matt Chan is principal of Scale Architecture and adjunct senior lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Sydney