table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

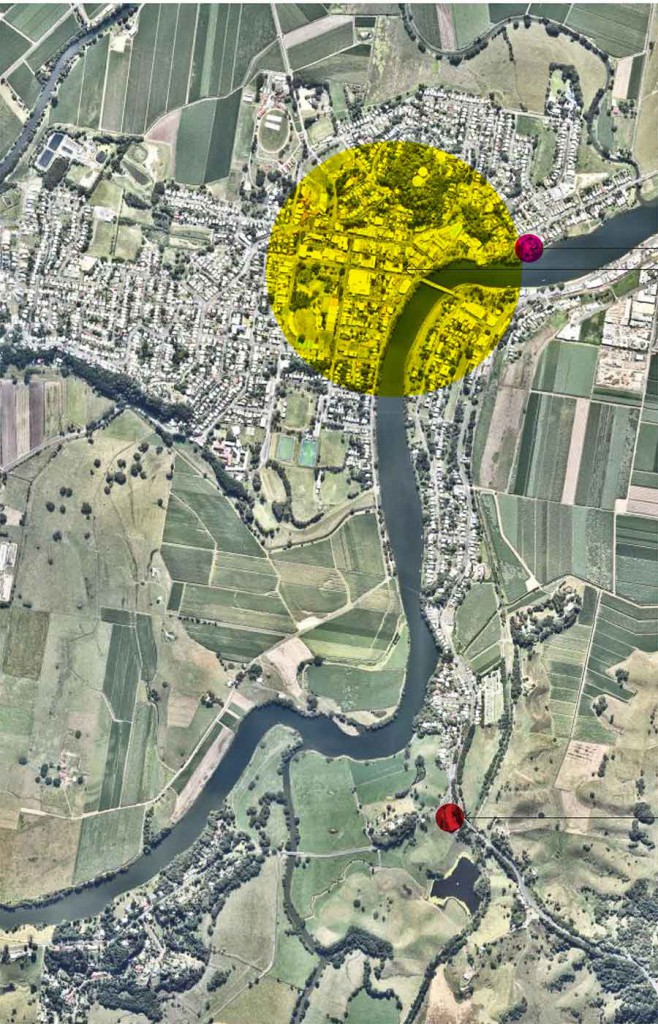

- Locating the Tweed Regional Gallery and Margaret Olley Art Centre, Murwillumbah (architect: Bud Brannigan). Photos: Dan Plummer and Peter Hyatt

The Tweed Regional Gallery has been a celebrated project, both architecturally and culturally, since its opening in 2004. The gallery is perched on a low hill in an undulating pastoral landscape that borders the Tweed River floodplain on the southeastern residential fringe of the Northern Rivers town of Murwillumbah. It commands sweeping views of the Tweed River, the Tweed Valley, and the green caldera backdrop including Mt Warning (Wollumbin), and the Border, Lamington and Springbrook Ranges.

More than anything, the current success of the gallery is a story of generosity. The site was gifted by the former politician Doug Anthony, whose farm takes up the foreground of the view. The most recent and very popular addition to the site is a result of a gift from the estate of artist Margaret Olley. Neither of these elements works by itself: the success of the architecture plays a significant role, as does the work of gallery staff in establishing an impressive collection, a schedule of public programmes and an appropriate tribute to Margaret Olley’s life and art.

The gallery was previously located in a Federation-era house on the edge of the Murwillumbah CBD. Its reinvention and relocation are mostly thanks to the efforts of the Friends of the Gallery, who raised a significant portion of the funds required to make the leap.

Architect Bud Brannigan worked with the new site’s location to design a vernacular ‘tin shed’ style building, that from the inside, frames spectacular pastoral and caldera views as emotive as any artwork. In this new space, the institution has been able to operate on a regional scale and sit within a fittingly-scaled landscape. A byproduct of this is that it also frees up the smaller heritage building in Murwillumbah for more intimate community-based roles.

The new gallery has become a significant regional drawcard. Visitor numbers have steadily increased since its opening and visitor numbers have doubled to 120,000 annually following the completion of the Margaret Olley Art Centre in 2014. However, its popular tourism status does not preclude local community use. For example, when the gallery is closed on Mondays the foyer fills with the quiet chatter of the local bridge club.

Applying the concept of placemaking to this project throws up some interesting contradictions. In this instance, two distinct types of placemaking are considered. The first focusses on placemaking on a regional scale – an institution that showcases a region’s landscape, culture and people. The second is the more community based perspective of placemaking – the reimagining and reinvigoration of place for the everyday benefit and betterment of a community.

These two perspectives are largely at cross-purposes. In order to succeed on a regional scale, there are a number of elements of community-based placemaking that are forsaken. The gallery’s commanding position within the landscape is favoured over convenient linkages and access within the local community in the town. However, the local council is tackling this issue by making the gallery the first stop of a rail-trail pilot program on the abandoned rail line from Murwillumbah.

The building does not really engage in any meaningful way with its immediate site due to programming and site planning decisions such as elevating the building off the ground to allow for undercroft car parking. This means that visitors enter the building through the car park. However, these were sacrifices worth making for the benefits gained in regional landscape appreciation. The payoff for entering this way is that once inside the building none of the site’s services are part of the experience. The visitor and the building are floating in a landscape context.

‘Is this an exemplary project for others that combine cultural and landscape appreciation? As good as any art or cultural exhibit may be, is it not the opportunity to observe the landscape and life from the calm and detached confines of quiet architecture that gives these places at least part of their allure?’

The Tweed Regional Gallery does not really succeed as a community/ grassroots reinvention if viewed through the lens of placemaking, but this is not a place for placemaking. This project, and the site are about place awareness. Upon entering the building the architecture is saying ‘this is the landscape setting in which you stand … and it is stunning’. The chief role and success of the building are to operate as an accessible, regional lookout that also houses an institution of considerable community and cultural value.

Could this project become a catalyst for a series of dispersed sites that take in spectacular or particular vantage points and panoramas of the Tweed Valley and its context? Is this an exemplary project and a teaser for others that combine cultural and landscape appreciation?

And is this combination of culture and landscape really key to the success of any such cultural institution? As good as any art or cultural exhibit may be, is it not the opportunity to observe the landscape and life from the calm and detached confines of quiet architecture that gives these places at least part of their allure?

In this instance, it is the natural and pastoral landscape of the caldera and the Tweed. Also, consider the wonderful light-filled riverfront spaces in Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art, where one can turn their back on art to gaze across the flowing river to the silent hum of the city’s CBD on the opposite bank. And the vista need not be grand. It is equally refreshing to stand at the large frameless windows in Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art and look at the much closer and intimate grain of the urban landscape.

The Tweed Regional Gallery project is an endorsement of the value of providing both local community cultural programs and a regional and national drawcard that blends and showcases two of the region’s key assets: a culture of creativity and a landscape of grandeur, biodiversity and history. The architecture, cultural programming and the landscape all leave visitors with a lasting impression of place and the desire for further exploration.

Dan Plummer and Belinda Smith are directors of Murwillumbah landscape architecture, art and design practice Plummer & Smith