table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

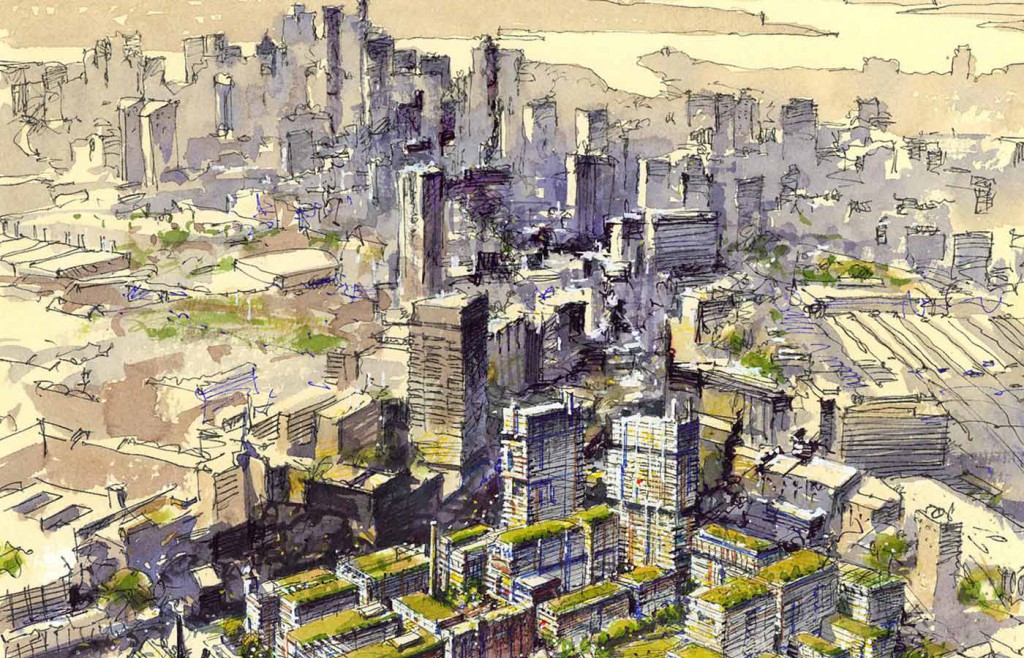

Designing Central Park, Chippendale

In the years between 2003 and 2009, the masterplan for Central Park, Chippendale authored through a joint venture between Tzannes Associates and Cox Richardson, guided the urban renewal of the Calton United Brewery (CUB) owned land in Chippendale.1 In 2007, the CUB sold this land to Frasers Centrepoint Limited (Frasers) and under the direction of Dr Stanley Quek of Frasers in 2009, Norman Foster + Partners authored amendments to the approved masterplan.2 The new neighbourhood in Chippendale, named Central Park, is the result of the work embodied in the masterplan process. This is a brief account of the masterplan process and design framework that underpinned the urban renewal of land that has become the precinct of Central Park in Sydney.3

The early years

In 2003, CUB sold an option to Australand to develop their redundant Chippendale brewery manufacturing plant and offices. Australand appointed consultants and immediately commenced work on a masterplan for the site. By early 2004, frustrated by progress on the resolution of design issues related to the masterplan, Australand under pressure from the City of Sydney, agreed to undertake a relatively novel design process – a design excellence competition conceived and endorsed by relevant authorities, for the selection of the scheme and lead consultant to carry out the required masterplan services. In parallel, the City of Sydney elected a new Lord Mayor, Clover Moore and with the support of her team of Independents, new and strong views were expressed about Sydney guided by a political agenda reflected in the Independent’s slogan ‘city of villages’. It was clear from the onset of the design competition that the new political leaders of the City of Sydney had a distinct focus on urban issues, with the CUB site as one of the more significant urban renewal projects to be used as an exemplar of their political agenda.

The competition was held based on a brief that included a reference scheme by Hill Thalis, that predated the newly elected government of the City of Sydney. A distinguished competition jury selected the scheme by Tzannes Associates / Cox Richardson (TZA / COX) ranked ‘1’ with no declared winner as the outcome.4/5 Following this outcome and as suggested in the jury recommendations, TZA / COX were engaged by Australand to continue with the development of the masterplan. The jury report, amongst a range of observations and recommendations, signalled concerns over what was seen as the excessive height and density set by the competition brief as an important reason for not choosing a winning scheme.6 Similar issues fuelled community objections to the redevelopment of the site and were at the heart of the concerns of the popular Clover Moore led council. Australand and TZA / COX continued the masterplan process for 18 months until 2005 without certainty about the preferred density and a range of related design issues. As a consequence, Australand rescinded on the option to purchase the land from CUB at a significant commercial loss.

CUB took the option to proceed with the masterplanning process, appointing TZA / COX. In contrast to prevailing community and City of Sydney views, TZA / COX supported significant density on this land, given the excellent transport infrastructure at Central Station and Broadway, proximity to major education institutions and a long list of other community facilities. Simply put, TZA / COX argued that if reasonable levels of density could not be placed on this site the unanswerable question was: where else in the City of Sydney and beyond could it be put? The level of density that continued to be proposed at this time for the urban renewal of the site was consistent with the competition brief.

By 2006, the redevelopment of the land was experiencing further delays reflecting the City of Sydney and local community concerns about the scale and density of the development. In June 2006 the then minister for planning and former Lord Mayor, Frank Sartor declared the site of state significance. In the context of ongoing controversy, the CUB masterplan DA was finally lodged in October 2006 and approved by 2007. By September 2007, the site was sold to Frasers on the basis of the development potential described by the TZA / COX masterplan.

Urban design principles underpinning the 2007 masterplan

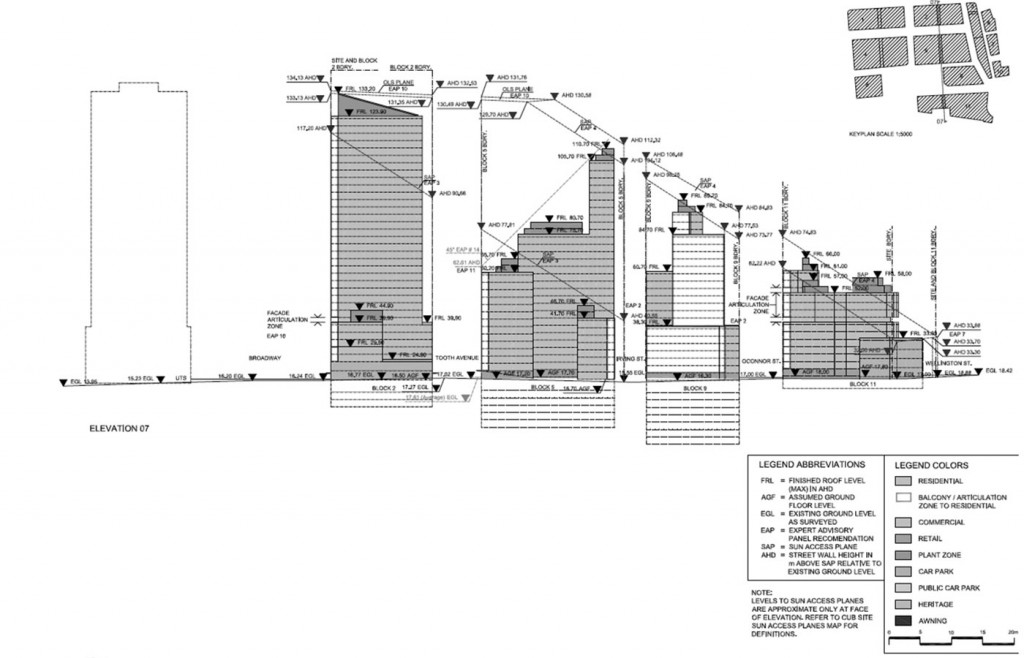

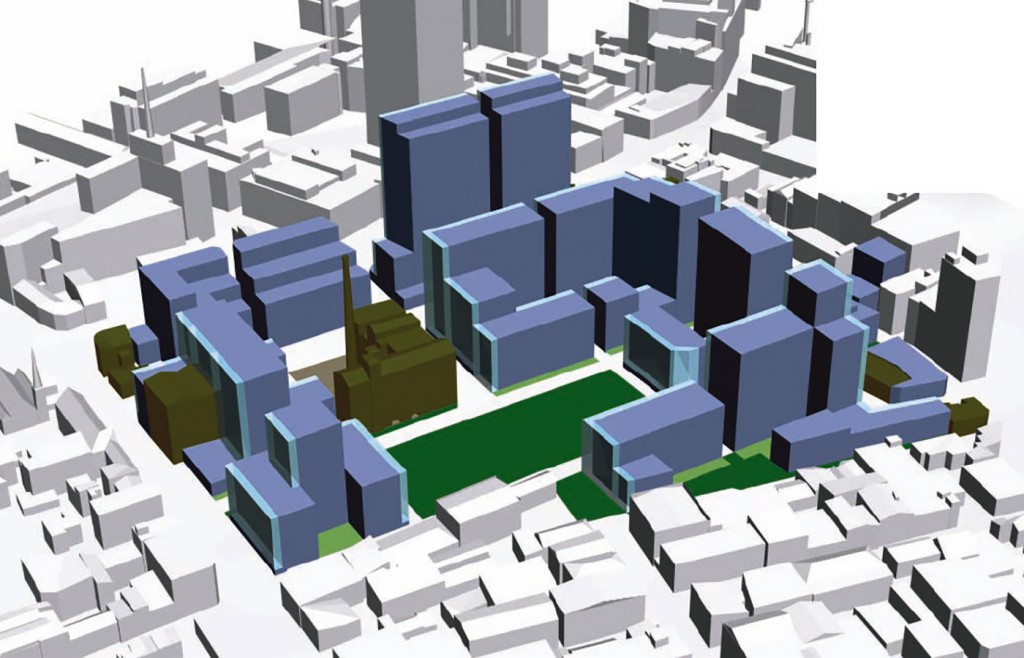

The urban design principles that underpin the TZA / COX masterplan are best understood by examining the development control drawings for the site. In these control drawings, the design of the public domain is given primacy. Development controls further reinforce the design of the public domain with measurable development requirements articulated in terms of the protection of public amenity.

The location of the park was reorientated from the Hill Thalis north–south axis to an east–west axis and relocated at the centre of the site to maximise its neighbourhood role and use, as well as to ensure the protection of heritage-listed subterranean drain infrastructure. The new park location was also placed to ensure all residents of Chippendale could now walk a similar distance not greater than 400 metres to any one of a number of public parks in the area. ‘Green fingers’ extending from the park completed the urban open space network by linking the park and major streets in the precinct through landscaping.

The second most important public domain element was the enhancement of Balfour Street to connect for the first time across the centre of the site on a north– south axis. Balfour Street became the only continuous link between Cleveland Street to the south and Broadway including the UTS campus, to the north. The extension of Balfour Street formed the primary urban structure of the blocks in the precinct and was conceived as major pedestrian-oriented experience crossing the new park and linking the major east–west vehicular streets to enhance retail opportunity and create exceptional residential addresses.

The neighbourhood streets beyond Broadway and Abercrombie Street were extended into the site to achieve an integrated street and lane network throughout Chippendale. The network of streets was calibrated to accommodate larger buildings primarily on Broadway and Abercrombie Street. The creation of Little Broadway, bookended by historic structures, was proposed as a pedestrian-focused and service road parallel to Broadway to enhance the potential of development on Broadway and to give a new experience for pedestrians. Little Broadway and Broadway framed the largest blocks with the greatest floor space and delivered the urban structure for the commercial heart of the precinct.

Kensington Street was identified as being at the heart of a distinctive precinct with the potential to become a major pedestrian-orientated retail and food destination. High level of protection associated with the smaller scale, heritage-controlled buildings in this precinct was another important element of the masterplan. The conception of the Kensington Street precinct was also informed by its placement between Central Park and Central Station and linked to Broadway, the main pedestrian corridor associated with existing public transport infrastructure.

The open space network, including the park and street pattern, was established in conjunction with practical building envelopes. One of the most powerful built form controls was the mandatory regulation of solar access to public open space (see figure 3). Other more subtle built form controls to enhance livability and public amenity related to the circulation systems designed to minimise the negative impact of service vehicles, loading docks, on street locations for building services and above ground parking. Of primary concern was the allocation of floor space and land uses in a built form that both related to the scale and character of the historic Chippendale fabric and responded to the large-scale buildings of the UTS campus on Broadway. One of the objectives was to ameliorate the negative perceptions of the architecture of the UTS tower by placing this structure into a more sympathetic context (see figure 4). Finally, the masterplan sought lower carbon urban initiatives in the detailed design of its elements including water conservation and management, roof planting and façade planting as part of water filtration, cleaner energy supply, effective cold air drainage and wind management, and the minimisation of urban heat sink effects (see figure 2).

The 2009 amendment to the approved masterplan

After the approval of the masterplan, Frasers purchased the site. Frasers visionary and design-focused leader, Dr Stanley Quek, embarked on a mission to regain the confidence of the local community and the City of Sydney through commitments to design excellence and more environmentally sustainable urban development.

He gained support from the City of Sydney for a blend of proven designers for commissioned works to enable an earlier start to the development process and committed to future design excellence competitions for the remaining parcels of land mostly located closer to the existing Chippendale neighbourhood borders to the south and west.

Frasers, noting the building footprints between Little Broadway and Broadway were at about 1,800 m2, were concerned that an anticipated market for commercial uses targeting the banking sector required footprints at 2,000 to 2,500 m2.

The requirement for an increase in the block dimensions for properties on Broadway was one of the most important drivers for the decision to review the masterplan and undertake a statutory amendment. Whilst there were a number of changes in the masterplan amendment, in many ways the change of greatest impact from an urban design perspective was to the street and block pattern. The proposed new street parallel with Broadway, Little Broadway, was moved further to the south and the proposed vehicular connection to Abercrombie Street downgraded to a through site pedestrian link. These changes enabled the requisite increase to the building footprints, setting off a suite of other related but relatively minor changes to the approved masterplan (see figure 5).

Central Park today

The implementation of the masterplan for Central Park by Frasers, and (from 2011) their joint venture partner Sekisui House Australia, is sufficiently advanced to reflect on the design principles that guided the development process.

The density proposed in the preferred competition scheme and subsequently exceeded by a relatively small amount in the amended masterplan is now generally accepted as appropriate for the site. This is evidence of the prescient nature of the original competition brief prepared by Hill Thalis for the City of Sydney. The design of the public domain and built form outcome as proposed by the masterplan has also generally been accepted as appropriate to the location and related infrastructure of Sydney.

Overall, the emphasis in the masterplan (including the amendment) on the design of the public domain has delivered a successful public domain outcome. Measurable amenity requirements for the public and private domain have been sufficiently practical and robust to enable a masterplan statuary amendment to be undertaken without major negative impacts on the original masterplan concept. The primary impact of the amendment to the masterplan was to reduce connectivity in the road and lane network arguably to the detriment of the amenity of the public domain. The level of connectivity has not significantly compromised the overall positive urban experience within the precinct, with the possible exception of the loss of Little Broadway including the impacts on the blocks linked to Broadway. Little Broadway, aligned with the axis of Broadway and Central Park, connected all the primary heritage elements within the precinct between Kensington Street and Abercrombie Street in a tree lined avenue form.

One less obvious consequence of the amendments to the street and block design is built-form outcomes at the boundaries of the site that are less related to the bulk, scale and character of the buildings within the adjacent Chippendale neighbourhood to the south, north and west. This outcome also contributes to Central Park as a precinct being more distinctive than the original masterplan envisaged as a special place in Sydney, to provide compensating urban benefits. Broadway is improved as a pedestrian experience. The negative effects of the UTS tower have been ameliorated. The park and open space network including the Kensington Street precinct have already established themselves as special places in Sydney and there is a general uplift in value, both material and cultural, throughout Chippendale as a direct consequence of the masterplan.

‘The commitment by the property owners to support good design in the fields of architecture, landscape architecture and engineering, including the implementation of lower carbon energy systems as well as highquality urban art, has greatly enhanced the masterplan proposition as a built outcome’

The commitment by the property owners to support good design in the fields of architecture, landscape architecture and engineering, including the implementation of lower carbon energy systems as well as highquality urban art, has greatly enhanced the masterplan proposition as a built outcome. This level of commitment to design excellence is relatively rare within the City of Sydney at precinct scale.

Overall the masterplan appears to have been a useful instrument to guide and control development with the high standard of realisation in design. This is a credit to the site owners, including their collaboration with the City of Sydney and the broader community.

Alec Tzannes is founding director of TZANNES and emeritus professor at UNSW Built Environment

NOTES

1 Masterplan project team for Central Park, Chippendale (2003–09): Tzannes Associates: Directed by Alec Tzannes and Peter John Cantrill.

Team: Allison Cronin, Adam Brewer, Amy Cruikshank, Julia Simpson, Natalie Brcar, Nigel Sampson, Robert Kitel, Neil Haybittel.

Cox Richardson: Directed by John Richardson and Nick Tyrell. Team: Michael Grave, Oleksandra Babych, Janet Vogels, Natalja Bartonez, Yue Wu, Kristen Neise, Belinda Hopkins, Deborah Young.

Landscape Architect (Sue Barnsley), Statutory Planning (JBA Planning), Community Consultation (Elton Consultation), Retail Advisor (Bonnefin Chapman), Commercial Advisor (CBR, JLLS, Colliers, Knight Frank), Civil & Road Engineering (Robert Bird Group), Environmental, Geotechnical, Hydrogeological (URS), Structural Engineering (TTW, Arup Structures, PDR Smart Structures), Services Engineering (Lincolne Scott / AEC, NDY), Water Sensitive Urban Design (Ecological Engineering), Heritage/Archaeology/Industrial Archaeology (Goden Mackay Logan), Access/Traffic (Masson Wilson Twiney), Waste Management & Recycling (Evans & Peck), Accessibility (WHP Architects, Access Associates, Morris Goding), Energy Efficiency (Heggies Australia, NDY, Lincolne Scott / AEC), Wind, Reflectivity & Acoustics/Daylighting (Heggies Australia), Shadow Studies (JM Computer Modelling), Photomontages/Perspectives (Haycraft Duloy), Modelmaking (Modelcraft), Surveyor (Cadastral – Degotardi Smith, Physical – Denny Linker & Co), Legal (Corrs), Heritage View Analysis (Richard Lamb & Associates), Solar Expert (Associate Director/Centre for Sustainable Built Environment UNSW).

2 This work was led by David Nelson from Norman Foster + Partners. The full team is not credited. Tzannes Associates (Alec Tzannes) provided supporting advice.

3 Central Park development timeline, designed by Dr Phillippa Carnemolla for the UNSW Built Environment Massive Open Online Course ‘Re-enchanting the City’ on FutureLearn, directed by Associate Professor Oya Demirbilek. http://tzannes.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Central-Park-Timeline.pdf

4 Competition jury: Graham Jahn (Chair), Russell Barnes, Keith Cottier, Richard Johnson, Robert Nation, Professor James Weirick. Refer to the competition jury report for the Carlton United Brewery Site (Balfour Park) design excellence competition. http://tzannes.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/CUB-SITE-JURY-REPORT-2004.pdf

5 Other competition participants: ARM, Bates Smart, FJMT, HASSELL.

6 The design concept within the brief was prepared by Hill Thalis.