table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

- Circular Quay image: airviewonline.com

Any final urban design proposals for Circular Quay should properly be the subject of national or international competition. This site, between the Opera House and the Harbour Bridge, is second to none in our city, and demands no less than such a public resolution. (Ken Maher, 1983)

Here is a small water inlet or cove symbolically entering the heart of the city, guarded on one side by the huge arch of the Harbour Bridge, and on the other by the unique form of the Opera House: the one, impressive for its monumental scale and simple form, and the other, with its headland-like base and sail-like vaults, capturing the spirit of the Harbour and the imagination of the world. (Elias Duek-Cohen, 1983)

What our current national president said 33 years ago still holds true today. The significance of Circular Quay as a place is without parallel in the whole of Australia. From the New Year’s Eve celebrations to the Vivid Festival it is the place we are drawn to for public celebrations in our city. As St Mark’s Square in Venice is the ‘drawing room of Europe’, Circular Quay is Australia’s maritime meeting place and promenade, a multi-mode transport hub where commuters and travellers arrive and depart against the unchanging backdrop of the Opera House and Harbour Bridge.

It is equally true that built-form interventions in this place give rise to heated debate, both within our profession and in the wider community. This again confirms the significance of the place, our attachment to it and our constant desire for it to be better.

The most significant changes to the place since the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 took place in the late 1950s:

– January 1956: Circular Quay Railway Station

– January 1957: Jørn Utzon wins the architectural competition for the Sydney Opera House

– March 1958: elevated section of the Cahill Expressway

The announcement of new designs for the wharves and boardwalk by Premier Baird in September last year was just the most recent of many attempts – some integrated but many piecemeal – that successive governments have made to improve the urban design quality of the precinct. Because the precinct can be perceived even by the casual visitor as an integrated whole, any attempt to improve part of it inevitably gives rise to calls for wholesale improvement and particularly renewed clamour for the removal of the elevated expressway.

But attempts to create a more unified precinct inevitably run up against the bewildering array of government and private interests with a stake in the future of the place. For example, despite the universally acknowledged historical and heritage significance of Circular Quay to all Australians – Aboriginal, long-term residents and recent arrivals alike – it has never been possible to develop a comprehensive conservation management plan for the precinct.

As Andrew Nimmo wrote 13 years ago in Architecture Australia:

Perhaps the root of Circular Quay’s problems lies in the way in which the responsibilities for decision making are divided amongst various groups that each have vested interests. Concentrated and layered within the Quay is perhaps the most complex array of problematic stakeholders that could be contemplated. While there appears to be considerable goodwill amongst these stakeholders to improve the Quay, there is actually no single authority who has the responsibility for the entire Quay. …

Major design initiatives at the Quay are generated at the political level when there is a perceived need for an upgrade, such as in the lead up to 1988 and 2000. In both cases the Government Architect managed the upgrade works, and battled as best it could through the long-winded process of stakeholder approvals. … Each clean-up will be tempered with the flavour of its time, as part of the general circular nature of design conformities. So along with the predictable build-up of accretions that must be chipped away, like barnacles from a boat, there will also be a ritual removal of items from the previous ‘clean-up’ that are no longer viewed in a positive design light.

For anything visionary and lasting to ever happen at Circular Quay (and that is not to say that anything visionary is actually required), there would need to be a change in how decisions are made regarding the Quay. Otherwise ‘tinkering’ will continue to be the fate of the Quay. – Architecture Australia, May 2003

As well as Nimmo in the Institute’s national publication, several Institute alumni have weighed into debates about the urban design of this precinct in the pages of Architecture Bulletin over the years.

But undoubtedly the high water mark in the Institute’s involvement in the future of the precinct was reached during Chris Johnson’s presidency in 1983. The phenomenal level of Institute activity during this period included:

– an ideas competition for the Gateway site at 1 Macquarie Place organised by the Institute following the designation of this site for a major development

– 92 submissions were reduced to eight finalists for presentation to the City of Sydney and a public exhibition of entries was held at the AMP building;

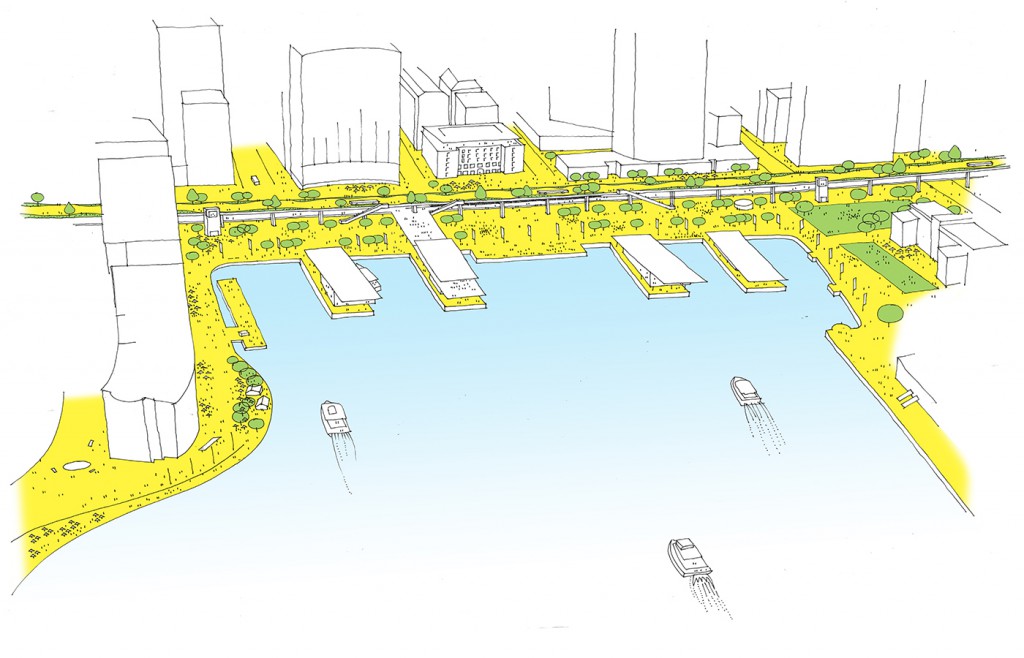

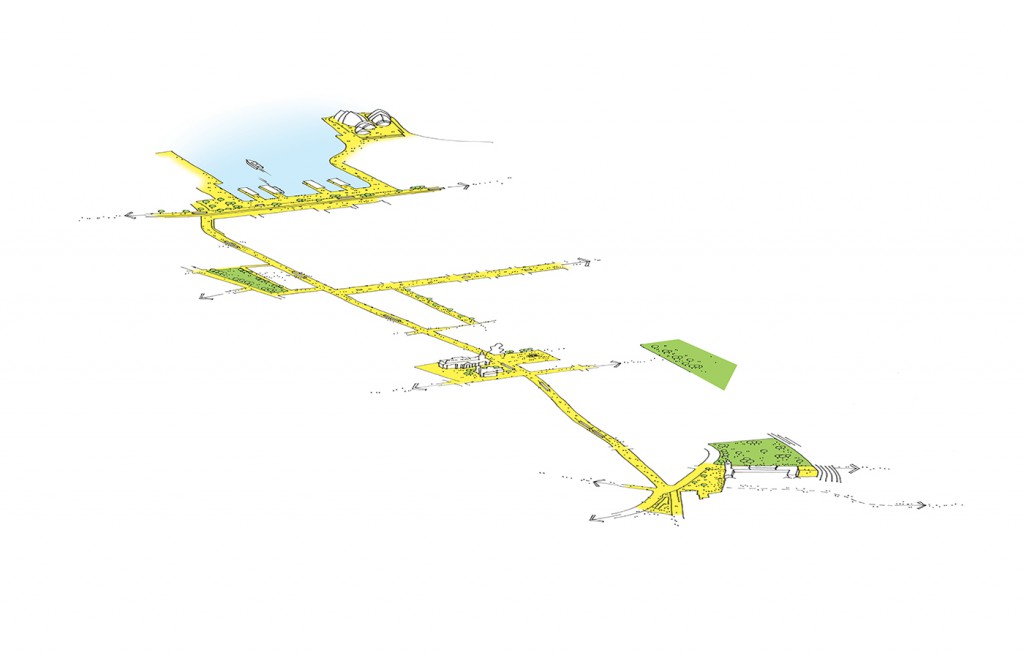

– the Quay Visions exhibition and associated book (edited by Ken Maher), which included articles on the history and planning of the precinct and 15 ‘visions’ for the future invited from practices ranging from Peter Myers and Richard Leplastrier to Ken Woolley, Conybeare Morrison, Philip Cox and the Public Works finalists in the Gateway competition;

– the ‘Conflict’ conference jointly presented by the Institute and Commonwealth Association of Architects that included a number of presentations on the future design of Circular Quay; and

– a second ideas competition by the Institute for the Overseas Passenger Terminal.

The Quay Visions project in particular flushed out some pithy principles for the future planning of the precinct that are relevant to this day, none more succinct than those of Neville Quarry and Francisco Urbina: throw out the clutter, invoke new forms, restore real public uses, create accessible public monuments and recapture confidence.

A complementary list was proposed by author and journalist Craig McGregor in the booklet: give people access to the harbour, make the railway transparent, keep the Quay maritime and keep it lively.

Taken together, these provide a useful first principles prescription for architects and planners today. As McGregor says: ‘the principles are more important than the plan’.

What does the future hold for Circular Quay? Where is the comprehensive plan that builds on the impressive work by the Government Architect’s Office in 1988 and 2000 to strengthen its unified sense of place and remove the accretions of the last 15 years?

We know there is a lot going on:

– upgrading of the Gateway building at 1 Macquarie Place, including three revitalised lower levels for food and beverage outlets (Woods Bagot);

– redevelopment of the AMP’s property holdings in the precinct to a Quay Quarter Sydney masterplan by 3XN, including a 49-storey tower at 50 Bridge Street (3XN & BVN) and connecting interface to the shorter tower at 33 Alfred Street (JPW), new development at 2–10 (Make Architecture) and 16-20 (Silvester Fuller) Loftus Street, 9–17 Young Street (SJB) the conversion of the former Hinchcliff Wool Store, 5–7 Young Street (carterwilliamson), into a retail building and public domain design by Aspect Studios;

– replacement of the Coca-Cola Amatil building by an apartment and hotel development (TZANNES) that also completes the East Circular Quay promenade;

– replacement of Gold Fields House by a residential tower and hotel (Kerry Hill Architects, Kengo Kuma & Crone Partners), laneways, new open spaces and pedestrian thoroughfares;

– Lend Lease redevelopments at 174–176 George Street and 33–35 Pitt Street including a 220 metre-high commercial office tower, with additional low-scale buildings, a public plaza directly accessible from George Street, a secondary plaza space on Rugby Lane and a pedestrian bridge link from the primary plaza to the commercial office tower podium; and

– redesign of the Circular Quay wharves by the NSW state government (Woods Bagot).

‘What does the future hold for Circular Quay? Where is the comprehensive plan that builds on the impressive work by the Government Architect’s Office in 1988 and 2000 to strengthen its unified sense of place and remove the accretions of the last 15 years?’

In addition, the draft Central Sydney Planning Strategy unveiled at the City of Sydney’s Transport, Heritage and Planning Sub-committee meeting in July includes a proposal for three new squares at Central, Town Hall and Circular Quay. The Circular Quay square will convert Alfred Street into a fully pedestrian precinct from George Street in the west and along the southern façade of the Circular Quay Railway Station to Young Street in the east.

But all this activity begs the overarching questions: What is the precinct masterplan underlying all this private and public investment? What are the associated public domain improvements? How are they to be knitted together into an integrated whole?

In recent years the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority, in association with other government organisations, has developed an urban design strategy to reduce clutter and re-unify the precinct under its management. But not only does this plan apply only to that part of the precinct north of Alfred Street, it hasn’t been released to the public, nor has there been any progress towards its implementation.

So where do we go from here? Have we arrived at another 1983 moment where the Institute, acting as an impartial but committed corporate citizen, could convene a discussion of all the precinct players to reach agreement on the broad principles to govern the future of the precinct? We did it once. Can we do it again?

Murray Brown is policy advisor at the NSW Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects