table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

Jed Long

.

As a co-founder of Sydney-based architecture collective Cave Urban, Jed Long approaches design with an emphasis on sustainability, community engagement and the continuation of vernacular tradition. He views the fluid relationship between art and architecture as a means to explore, create and test new structural systems outside the confines of the architectural profession

.

.

Rana Abboud

.

Rana Abboud is a project architect working at BVN. Her practice, independent research, university teachings and interactive art installations revolve around cutting-edge technologies that have the potential to shape the architecture industry’s future

.

How do you practice within the field of architecture?

JED LONG: I practice as part of an experimental architectural practice called Cave Urban. We collaborate with a diverse range of international artists, organisations and experts who introduce us to a range of design methodologies, philosophies and global communities. We treat every installation as an opportunity to experiment with ideas. What we create as art or pavilions filters through to our architectural practice, with clients becoming engaged with and inspired by the philosophies of design we are exploring in our public work.

RANA ABBOUD: Since completing a research Masters at Berkeley over a decade ago, I’ve been working full time within established architectural practices while indulging in freelance competitions, university teaching and independent research as a creative outlet. I’ve recently resumed my role as an architect at BVN after a whirlwind year spent on maternity leave, in which I ran a final-year design studio at UTS and completed my third interactive installation for the VIVID light festival with my husband Ewen Wright. I’ve also found that it has been through installation art that I’ve been able to experiment with ideas about space and technology.

Can you define your principal architectural ambitions?

RA: I’m fascinated by how new technologies can shape the way we live and work. One of my main ambitions is to contribute to explorations and discussions about cutting-edge technologies that have the potential to shape our industry’s future. Winning the NAWIC International Women’s Day Scholarship in 2013, enabled me to research the opportunities and obstacles for the key disruptive technology of our time: augmented reality (AR). My study tour around the US and Europe allowed me to meet with AR’s pioneers, piquing my interest in the medium’s potential across all phases of architectural practice.

JL: Practicing in an interdisciplinary arena allows us to define our own identity and design philosophy. Research and experimentation at the junction of art and architecture allow us to challenge traditional architectural paradigms. Recently I was awarded a Byera Hadley Scholarship to research the notion of permanence. Western society often associates permanence with materiality and durability. Cultural and social relevance is a far greater determinant to the longevity of a building. Cave Urban engages with these notions of impermanence by creating temporal structures, which enables us to engage with space, landscape and the experience of the inhabitant. Most importantly, a sense of community is established by those participating in the build.

Can you describe a particular project you have engaged with which has been developed in that ambition?

JL: Last year we created a work titled Near Kin Kin for Art & About Sydney. It was a 24-metre-high tower of bamboo that sat in the forecourt of Customs House, setting up a relationship between the two forms. The organic materiality of bamboo, which allows for complex spaces to be created in a short time frame, was intended to juxtapose the surrounding urban environment. We aimed to create a structure that enveloped visitors in an internal space that evoked the sensations of being submerged in a forest.

Since bamboo is abundant throughout much of the developing world, it is recognised for the important role it can play in post-disaster relief. By recontextualising the knowledge I have gathered through experimental architecture and art, I have been able to apply it to a humanitarian setting. This process has in turn generated new ideas that we can then bring back to the other components of our practice.

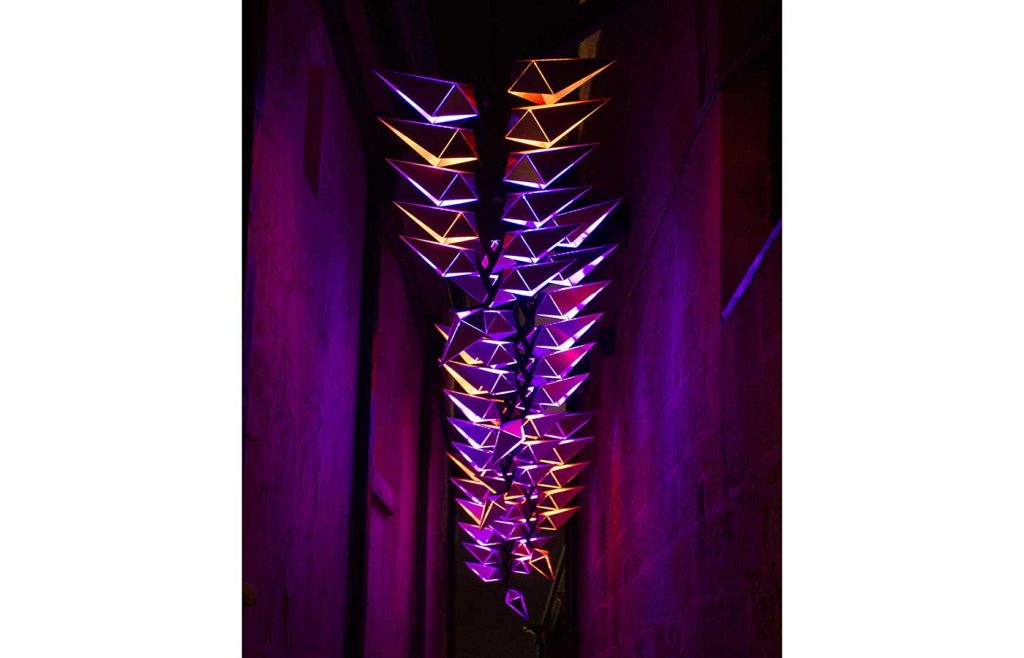

RA: My installation art has also allowed me to develop my ambition, which relates to exploring ideas around technology and the built form. From my VIVID installation DIGITALIS (2013) and CLAPICONIA (2014) to this year’s UNFURLII, a recurring theme in my installations – each completed on a shoestring budget in our spare room – has been the interaction of ‘sentient’ creatures with an audience. UNFURLII, for example, was designed to kinetically curl itself up and move out of the reach of its audience below. While initially presenting as a visually static ladder of light bars, it surprised viewers by moving and changing colour when they reached up to touch or engage with it. The potential for architecture – largely a static enterprise – to similarly morph and engage with people through embedded technologies intrigues me greatly.

How do you see those ambitions in relation to the wider practice of architecture?

RA: My fascination with the new technologies that stand to impact our profession has much to do with wanting to make environments more responsive to their human audience. Today, the practice of architecture revolves around buildings that are largely frozen in space. What if technologies could allow the frozen physicality of a building to alter and interact with its occupants in more useful and engaging ways?

JL: I am also interested in how environments respond to their inhabitants. I believe that buildings are not finished objects, but enablers of transition. Often we make the mistake of assuming that once we sign off on a building that it is finished. This occurs in any setting from an emergency humanitarian response to a public building that serves the needs of an ever-changing community. Community engagement from the beginning of the design process ensures that current needs are met but it can also help forecast what may occur in the future. A building, no matter what it is made of, will not last long if it fails to engage with the cultural, social and climatic issues of place.

Do you see these ambitions as reconciling a current deficit in the practice of architecture?

JL: Yes, very much so. I think computers are incredible tools for design but I find at times they propagate flat architecture. Where is the connection to the wider historical tapestry of place, to a sense of materiality or a profound spatial experience?

The failure of architecture to adapt to the changing needs of society contributes to the rapid rate at which we demolish buildings to create another. This is a process that is completely out of sync with the notion of sustainability.

RA: I think the appetite for the risk to trial new technologies does not exist with most building projects. Understandably, clients rarely accept the possibility of failure inherent in risk-taking. There is a gap between the frontline of technological research and development – be it in academia or private industry – and architectural practice. My thesis advisor at Berkeley, the former director of the Centre for New Media, often said that architectural practice was roughly ten years behind pioneering academic research, due to the conservative nature of our industry and its resistance to change when faced with new technologies.

What are your thoughts on the future of architectural practice?

RA: I am optimistic about the future of architecture practice. For so long, architects have coded information about 3D objects using predominantly 2D means, and the emergence of new technologies that bring with them new ways of looking at information will disrupt this tradition. Architects today are aware of the history and skill required in freehand drawing to communicate ideas; are using BIM; and eventually, will discuss workflows where BIM is a prerequisite for other media, including AR. New roles will emerge – similar to the model managers brought about by BIM – and, inevitably, new frustrations with technology will surface also. What an exciting time to be an architect!

JL: It is realistic to assume technology will play an ever-increasing role in our lives. I think the question then becomes: how can the practice of architecture maintain meaning in the presence of an automation of process? What I desire is a timeless architecture that gives new meaning to the works of the past and supplies context to the works of the future. The answer lies in non-homogenous architecture that can adapt to the needs of the community. This idea does not necessitate technological innovation, as different cultures have been creating buildings that can change to suit various uses for thousands of years. Instead of dismissing vernacular building as nostalgic, we should respect how these forms have adapted to suit their climate, landscape and culture.