table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

David Kaunitz

.

David Kaunitz is an architect with 15 years experience. Through his current practice, Kaunitz Yeung Architecture, David works on projects for the governments of Australia, New Zealand, European Union, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Cook Islands, Philippines, UNICEF and World Vision. David is also a director of the small engineering NGO Partner Housing Australasia and has helped set up two local NGOs in the Solomon Islands under the banner of Ranongga.org. Through these, David continues to help design, develop and deliver innovative grassroots community-led projects

Can you describe the way in which you practice within the field of architecture?

DAVID KAUNITZ: We are Sydney based but we work outside of NSW and Australia. What differentiates us is our methodology. This methodology is based on collaboration with clients, stakeholders and local communities, and requires the starting point to be in listening and being devoid of preconceptions. This includes the preconceptions of the community and of the architectural outcome. The architecture must be allowed to become a reflection of the community, guided but not determined by us. Only through listening can the understanding of local culture, building practices, capabilities and desired outcomes be understood.

This takes time. It cannot be rushed and requires that we spend significant time within the community as there are a hundred small things that can only be learned in the queue at the shop or chatting under a tree. Time in the community also enables iterative consultation to develop the design in a way that is visible to the community. This transparency enables the

community to understand the logic of the final design and, most importantly, to build trust in the outcome. The consultation itself is broken into focus groups to enable different perspectives to be heard. This includes workshops at local schools where children can learn about the process and draw their ideal building. This level of engagement always delivers surprising feedback and facilitates a deeper connection with each family. Overarching this is the engagement with local leaders. Where possible consultation is run by respected local people and, where required, in the local language, which provides immeasurable benefits, particularly in Indigenous Australia.

Within that manner of practice, can you define your principal architectural ambitions?

I have always had ambitions to work in the Pacific Islands and Indigenous Australia. This came from key childhood experiences with indigenous people and in the context of being the first in my family to be born in Australia. My early architectural work had a particular focus on civic, health and social housing projects that has enabled me to develop skills and appreciation in consultative practice. Through my voluntary work with Emergency Architects Australia, I have further developed my skills in the context of the Pacific Islands, which has shaped my architectural practice.

Can you describe a particular project you have engaged with which has been developed in that ambition?

In 2011 we were commissioned to develop a ‘hybrid’ standard classroom that would be applicable across Vanuatu. The aim was to increase the use of local materials and skills whilst meeting western construction standards. Following consultation with all levels of the Ministry, a design was developed and a prototype built at Takara Primary School, North Efate, Vanuatu.

The prototype was constructed entirely by the community. Roof panels and window hatches were made in local villages. This has the benefit of ensuring the community possesses the skills to maintain the building and carry out repairs post-disaster. Anecdotal evidence suggests that student engagement and learning has improved in the new school building.

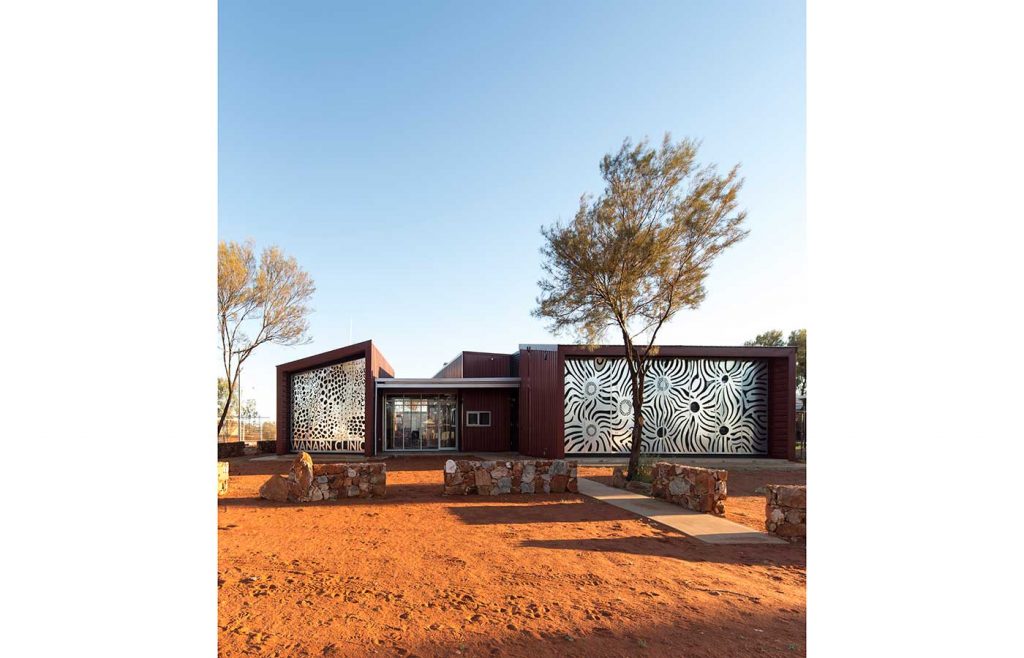

We have numerous community and remote area projects in design and construction in places such as the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, Western Australia, Tiwi Islands and Northern NSW. These projects include health clinics, an arts centre, community centre, childcare, tourism office and housing. This provides a platform for us to continue to work with communities in a meaningful way whilst further developing our methodology of practice.

How do you see those ambitions in relation to the wider practice of architecture?

As architects, we can all agree on the importance of a well and thoughtfully designed built environment and the importance of architecture in shaping our world in an inclusive and sustainable way. This is as true in Sydney as it is in a remote community. Remote communities often by nature are underprivileged despite their rich culture, heritage and resourceful people. All too often the approach in these communities is haphazard or engineering led. The result is an unsafe or soulless built environment. There is no reason these communities should not benefit from architecture in supporting and complementing community development, sustainability, aspirations and self-esteem. For the development and sustainability of all communities, it is imperative that an architecture-led approach be used in these communities.

.

.

MAPA

.

MAPA (Moline Axelsen: Public Art / Participatory Architecture) makes works of architecture and art. These works range from buildings to objects and installation, social processes and community engagement and situated public art. Directors Hugo Moline and Heidi Axelsen have been working together since 2008 and are members and co-founders of Sydney-based collaborative design collective The Lot. Together they have built and exhibited work in various locations across Asia and Australia

Can you describe the way in which you practice within the field of architecture?

MAPA: Alongside more traditional modes of architecture and visual arts, we work in a hybrid practice: making artworks that engage at an architectural scale, while bringing the criticality of an arts practice to issues of architectural concern. We work at a variety of scales, from animated maps to multi–unit residential and from urban insertions to the collaborative city plans.

Through our situated public arts practice we work on micro-architectures, nimble urban insertions that test ideas more rapidly and with more freedom than traditional architecture allows. We view each project as practical research, operating on social, historical and material levels.

Through our larger building projects, we extend this notion of prototyping to formulate alternate possibilities for housing and public space. In these projects, the research is mostly at the level of finding built form to accommodate innovative social forms.

Can you define your principal architectural ambitions within that manner of practice?

There were people who taught us at Sydney University who were huge inspirations like Col James, Paul Pholeros and Anna Rubbo. Various research scholarships also enabled Hugo to travel to Thailand to work with CASE Studio, to San Diego to work with Teddy Cruz, and visit New York to see organisations like the Centre of Urban Pedagogy. For Heidi, after studying sculpture she was keen to expand into public artwork. From her work in cultural development in Fairfield, Heidi developed an appreciation for engaging with diverse communities. Both these shaped the way we work together as MAPA.

We’ve got this idea of the ‘prop’. It’s the object we’re focusing on. It’s the Bruce Lee quote where you have a finger pointing at the moon. ‘Don’t concentrate on the finger, or you’ll miss all the heavenly glory.’ We’re concentrating on the finger – we’re making this thing but it’s for another purpose. It allows you to look at the moon. We might be working on a site-specific installation or a housing project or a map for the city or a utopian scheme, but it’s about building a community around it. And there’s a real lack of collective solutions at present – it’s very individual focussed. We’re trying to make little knuckles that bring some sense of the collective possibilities.

Can you describe a particular project you have engaged with which has been developed in that ambition?

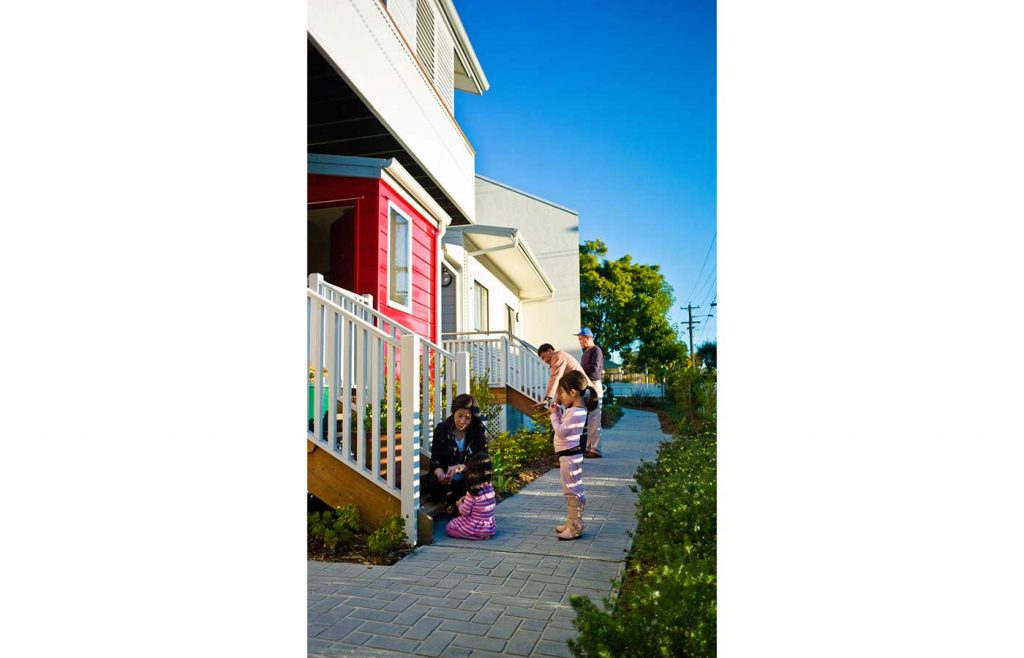

Kapitbahayan is a project composed of six attached houses and common facilities for Kapitbahayan, a Filipino housing cooperative in Western Sydney. The new housing was designed in close collaboration with members and tenants. Kapitbahayan (meaning neighbourhood in Tagalog) is an alternative, community-driven model of housing design and management. The design harnesses the knowledge and passion of Sydney’s immigrant communities to create a housing model to combat unaffordability, sprawl, social isolation and housing obesity.

Owner Occupy is a more recent project that questions the basic relationship between dwelling and ownership in contemporary Sydney. The project explores the possibility that Terra Nullius could be declared again, as a new and permanent state: Terra Nullius Ad Infinitum. Rather than through violence or political reform, this project asks if the return of land to common property could be achieved through an incremental spatial operation. This brave-new-world will be built from a series of handbuilt dwelling machines. Light, highly detailed and flexible structures of timber and canvas. These can be reconfigured, modified and combined by their occupants to create diverse spatial arrangements for personal and collective dwellings. The basic premise of these dwelling-machines is that whoever occupies them, owns them.

How do you see those ambitions in relation to the wider practice of architecture?

The sheer expense of making architecture predisposes it to operate on a mercenary basis. Designing for, and by extension, in the interests of, those with the political and financial power to buy, build and hire.

We are inspired by all the practices, which seek to step outside the mercenary paradigm. To build alternative bases of power, to perform critical, self-initiated projects and build networks around them in order to make their utopias real.

We’re trying to establish a durational approach into early stages of developments. We’re referencing models in Bristol or Copenhagen, where artists get early involvement and team with urban designers and architects, to work collaboratively with the community to generate portions of the development. It’s an embedded process that allows us to look at the concerns that we’ve been looking at, but at a bigger scale. This approach is needed everywhere. In a way, it would be interesting to work in a suburb like Mosman to build community there.