table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

UP (Urban Possible)

.

UP (Urban Possible) is a small studio working on BIG projects. Sean Choo and Simon Fleet met whilst working on large scale multi-residential and mixed-use buildings at Grimshaw. With backgrounds in designing anything from bespoke houses to major infrastructure projects, they quickly realised that the thinking and intelligence embedded at the small scale are not that different to that which could enable the world’s tallest skyscraper. When they established their practice in 2014, it was with a clear goal to not be constrained by scale

.

.

Stewart Hollenstein

.

Matthias Hollenstein and Felicity Stewart are two friends who share ideas about the design of the built environment and its role in society. They formed collaborative studio Stewart Hollenstein in 2010 with a specific agenda to put meaningful human experiences at the centre of the design process, and in 2013 won the international design competition for the Green Square Library and Plaza in Sydney

.

How do you practice within the field of architecture?

STEWART HOLLENSTEIN: We operate primarily as an architecture and urban design office. We use projects to explore the potential for architecture and habitation. We have taught at universities as a means of research and to share our methods and values with students to allow them to empower their own future. We also share our work with the public through talks, presentations and workshops. Our studio is set up as a co-working space for community events, exhibitions, architecture, art and fitness classes as well as photography shoots. As much as we love our work we also try to spend as much time as we can enjoying life. This is where you find inspiration and insight!

UP: We have a nine-to-six practice as a matter of fact; we rarely work outside these hours. We both have young families and we agreed, from the start, that family would always come first. This is not to say that we don’t have a strong career ambition – we choose to focus on the things that matter most and aim to be as efficient as possible.

On efficiency, we believe that the Pareto principle applies to the field of architecture. For most projects, it only takes roughly 20% of our time to establish the spatial organisations, which accounts for 80% of the effects experienced in architecture. If we were to focus on the front end of projects, we could theoretically set the bones for up to five times as many projects, and thus create a broader social footprint. We aim to maximise the net effect of our time.

To achieve this successfully, we seek out opportunities to collaborate with large, established and technical architects. This model has provided us the space to set the agenda and aspiration of projects, to establish the priorities and reimagine the possibilities – to dream bigger.

SH: We also work across different scales, from signage and furniture to city scale and systems thinking. We don’t limit ourselves to a certain scale or way of thinking when approaching a project. We are interested in expanding the potential for human connections in all our projects; we find this the best way to understand the body’s relationship with the built environment.

Can you define your principal architectural ambitions within that manner of practice?

SH: Society is facing many challenges, some are urgent, some are every day, some are old and some new. As architects we are interested in tackling these within our work. We are interested in the social agency of architecture. As much as architects can only address limited aspects of these challenges, it is important for us to recognise that we can still have a role if we choose. This approach almost always expands the project potential and gives the project momentum.

UP: We simply want to do good work; work that is responsible to both users and owners. There has been a paradigm shift in the way architecture is perceived thanks to the proliferation of social media; it is increasingly judged by photography and renderings. We are disturbed by the amount of architecture awards that have been given to buildings that look great on paper but are not practical for real usage. A lot of (unnecessary) time and (the client’s) money are spent to ‘apply lipstick’, more for the architect’s self-gratification than for the need of the client and users.

We are also critical of ‘overdesigning’ in architecture. Too often we see architects reinventing the wheel only to cause more unforeseen issues. We see design as problem solving; if there is no problem, there is nothing to solve!

Can you describe a particular project you have engaged with which has been developed in that ambition?

SH: There’s the Broken Hill Library, the intention of which is to create a meeting place for the community and visitors and to encourage interaction with the street in a strong and positive way. We’ve added elements to the brief which heighten the potential for knowledge sharing and storytelling, expanding the role of the library as a cultural facility.

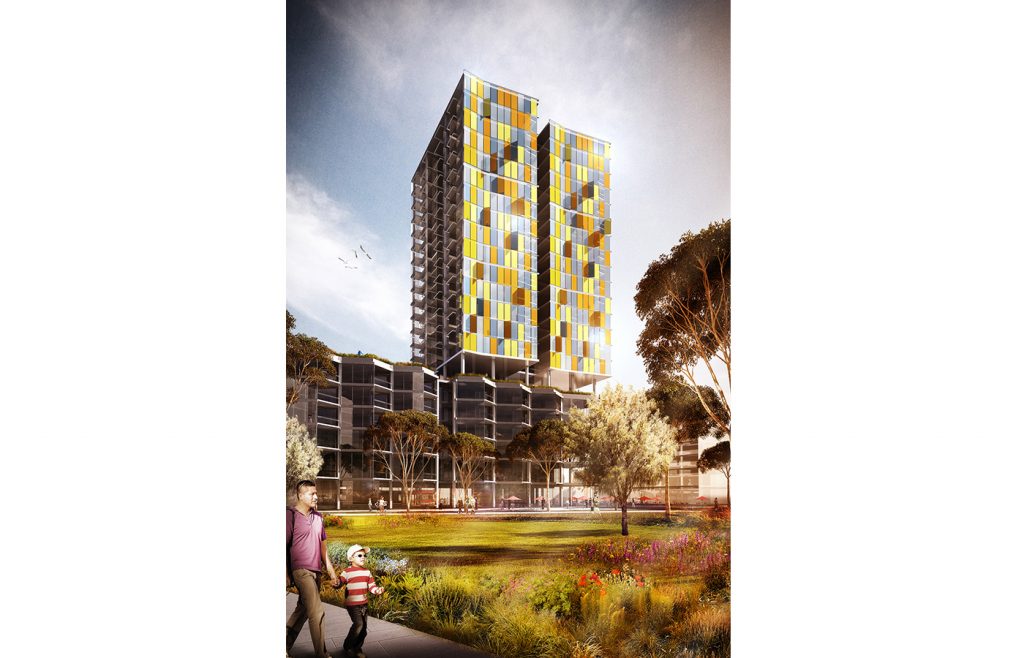

UP: We recently came very close to winning a design excellence competition for a mixed-use tower overlooking Hyde Park in Sydney’s CBD. The City of Sydney initially endorsed only five established practices for the competition and we were only involved at the insistence of the client, for whom we had secured a great Stage 1 DA outcome.

Our scheme was shortlisted as one of two and cited for its legibility and clarity. However, in the end Council was not prepared to consider our variations to discrete DCP controls. We were, of course, disappointed but have learned a lot in the process, including the politics behind DECs, which paradoxically were initiated to tease out alternatives that have a better outcome!

SH: We’re also working on an apartment project in Lidcombe in Sydney, in which we are looking at ways that we can create a flexible unit design that can evolve as the resident’s life changes. How do we design a unit that can be purchased by a single person, cater to their life once they’re in a relationship and allow for the expansion of that family?

How do you see those ambitions in relation to the wider practice of architecture?

UP (Urban Possible): The industry needs to take young practices seriously. We don’t lack the creativity; we only lack the technical support to document the big ideas we come up with. The perception of risks with small firms could easily be negated if the industry accepts the idea of collaborations. A normal team required to deliver a large project consists of well over a dozen consultants – so why is there a preconception that the architect needs to be a singular practice?

Do you see these ambitions as reconciling a current deficit in the practice of architecture?

SH: Such a loaded question! Any deficiency surely forms a new opportunity. All deficits can be resolved if we start looking into the critical issues facing society. This is where the architect’s relevance lies. The questions for architects are: How do you use the design of your work to take society from where it is to where you want it to be? How do we become part of the conversation on where society is going? Once there, how do we make room for others and how do we collaborate effectively?

UP (Urban Possible): Absolutely. The same handful of starchitects are designing our cities and a much wider group of equally capable designers in small practices are confined to small alts and adds in the suburbs. The city is becoming monotonous with the same designers chosen by reputation more often than by scheme. Design excellence competitions are in place to tackle exactly this issue, but it seems that we have fallen back to the comfort of selecting brand rather than excellence.

SH: If it’s the architect’s responsibility to imagine the city and the way it could be, then it is important that their expertise is present in those broader discussions. For instance, it’s incredibly heartening to see Phillip Thalis elected to City of Sydney Council. That’s not to say that you need to enter politics to be an architect, but instead that we should understand architecture as a political act.

UP (Urban Possible): Of course, not everyone yearns to design large buildings but we suspect that given the opportunity most would be keen!

What are your thoughts on the future of architectural practice?

UP (Urban Possible): We hope to see a lot more collaborations between architects. Architecture requires such a wide variety of skills that it isn’t ridiculous to further break down the practice into sub-professions. The more we specialise, the more we could tackle the key issues efficiently – an architect should not be a jack-of-all-trades, but should know who to collaborate with to best engage a project. It is a win-win for clients who risk neither a great design that is impossible to build nor a robust building that lacks imagination.

SH: The future is bright! We are excited about architecture’s potential. In a world that is rapidly urbanising, whose rural spaces now have enormous pressures on them and where borders are becoming contested, architecture and the knowledge of how we use that space can only become more relevant. As we address these issues it is important for us to keep the human at the centre of our design and decision-making process. We have to place human enjoyment and benefit at the heart of our work.