table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

Reflections on Paul Pholeros and the thingness of things

Paul Pholeros AM (1953–2016) was a Life Fellow of the Australian Institute of Architects and co-founder of Healthabitat, an organisation working with remote, urban and rural communities for over thirty years to improve amenities and thereby their health. Here are some personal accounts of his life and work

EXCEPTIONALLY GIFTED, the architect Paul Pholeros worked for the better part of his life improving the health and wellbeing of our first Australians. Concurrently he ran a small-scale practice as well as being a great teacher to architecture students, emphasising such vital principles as landform, sunshine, clean air, clean water and wellbeing. He demonstrated both brilliance in thinking and humaneness of action throughout the clear streaming of his life.

I first met Paul in the 1970s when he was an architecture student at the University of Sydney, where I was a practising tutor at the time. It was always such a pleasure working together. When reaching 4th year it was common practice for the students to take the ‘year out’ into the real world. Paul and a group of like-minded mates bought an old bus in which to travel around the country. They had it all in pieces, including the engine, dismantled in the backyard of the faculty and making full use of the school’s workshop. It looked like Steptoe and Son’s junkyard. The subsequent journey around Australia was an epiphany for Paul. He came to realise at such a young age that Aboriginal culture and its foundational relationship to the land underpinned the future of this colonised country and that their health and wellbeing was essential. This set the ethic for his life’s work and he never wavered from that.

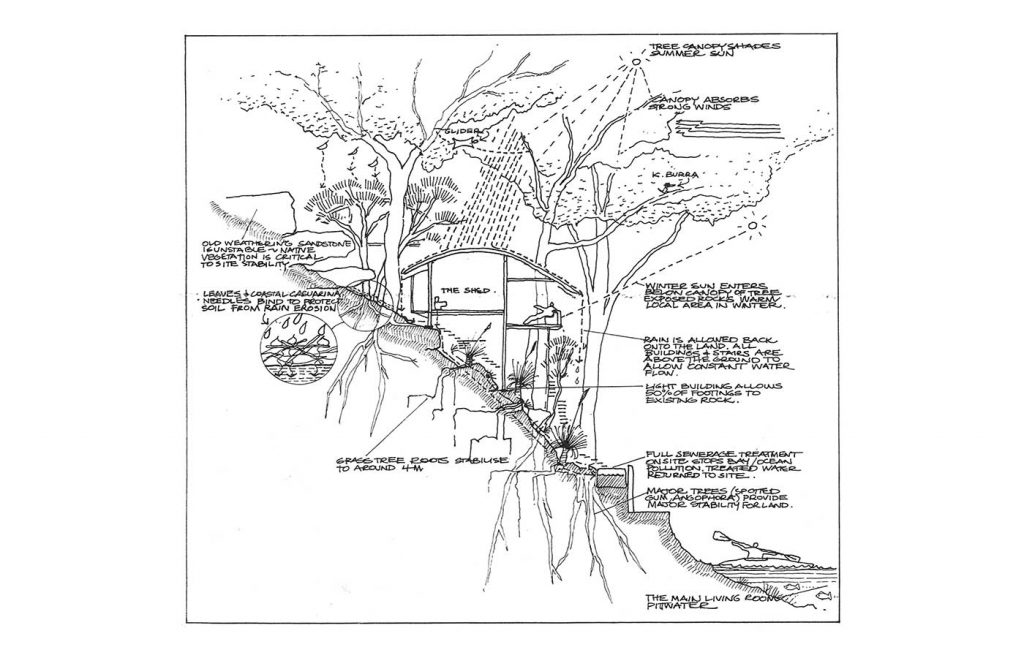

Much has been written about this extraordinary dedication to helping under-resourced communities through his Healthabitat work with Dr Paul Torzillo and Stephi Rainow. But little has been written about his modest private practice. Here, he always first had the land in mind: ‘If in doubt don’t build at all, and if you do, then build it small’. All of these works he did are beautiful, both in conception and construction. Through his modesty few were ever published, but we watched and were inspired. With his life partner Sandra Meihubers who introduced him to the APY Lands,* they made a sublime minimal house in the Hawkesbury sandstone terrain, up high in the treetops on long legs barely touching the bush surrounding. Facing the north sun and protected from the difficult winds by hills behind, with walls opening up under a great overhanging roof, they have created an exemplar for an architecture that belongs to its place. It is a master work.

When Doshi, the famous Indian architect, told Louis Kahn, the great American architect about the death of Le Corbusier, Kahn was silent for a moment and then quietly said: ‘Who shall I work for now?’ Confronted with the loss of Paul Pholeros, we all may well ask the same question.

Richard Leplastrier, Architect

WATCHING HIS AUNT Dorothy sketch fashion designs, a young Paul Pholeros would observe her skill with a pencil as she created elegant forms and styles. Dorothy nurtured Paul’s own drawing ability, which he then used throughout his life as a powerful observation and communication tool. In adulthood he coupled this skill with his wry perceptions of life to create ‘cartoons’ – clever commentaries on the often absurd machinations of society, more specifically of bureaucracies.

Dorothy was a keen body surfer, as was Paul’s father Cecil. They would spend hours in Sydney’s surf, Dorothy unfazed by the occasional dumper, the young Paul clinging to his father’s back as Cecil expertly rode the wave right to the sandy edge. Cecil was a businessman with a sharp instinct for the truth, and a gentle yet clear intolerance of fools. A large man with an outgoing personality, he was the life of any party, a man much loved and admired by his son.

Cecil was also a lover of all things related to waterways and would take Paul sailing in a tiny dinghy, teaching his son a respect for the water and the elements. After several spills, sometimes orchestrated intentionally by Cecil, Paul learned how survival in rough conditions required real skills and how to balance risk with caution.

Growing up with a blend of cultures – a Greek family on Cecil’s side, a rural Australian background on his mother Betty’s side – Paul was exposed to the varying world views expressed by each. Extensive travels in Australia, Asia and Europe in his early adult life enhanced this knowledge and formed the foundations of an ever-evolving interest in others. Paul would ‘look for the similarities not the differences’ in people, while sensitively respecting the differing influences on someone’s life. More importantly he saw that through his architecture he had the means to improve people’s lives, be they remote dwellers in poorly built and maintained community housing, or well-resourced individuals wishing to ‘build a house’.

PP, I thank you for all that you gave, and for all that we shared.

Sandra Meihubers, partner of Paul Pholeros

PP loved Australia, the country, the people who lived in it and respected it, and whoever wanted to learn about land and country, against a wealthy society’s lazy habits. He learned and taught about Australia by going bush, quietly listening, and looking, really, really close, like it was all a great music, a huge art. As we are still trying to learn.

John Roberts, Lecturer (architecture), University of Newcastle

I CAN REMEMBER first meeting our friend at 3 Wilkinson St, the Pitjantjatjara Council Office in Alice Springs. He wasn’t just my friend, he was a friend for Yankunytjatjara, Pitjantjatjara and a lot of other Aboriginal people in the NT. Later on in life I found out he was a friend to many overseas indigenous people as well.

Our friend, Paul Pholeros was a major key person for Uwankara Palyanyku Kanyintjaku, a strategy for wellbeing. Paul changed the lives of many Anangu and the first project started in Pipalyatjara.

I can remember he told me the living standards of our people was sheer horror and I bet he never forgot the smell of waste water that seeps through the house. Paul would often say, ‘If you change the environment, health changes’.

Everybody told me that Paul’s designs for the new houses were perfect, ‘they were real Anangu friendly’. I travelled out to Pipalyatjara and looked around the new house with my seeing eye fingers. I felt good, it was a job well done and I thought Anangu would be happy and our health should be getting better.

Our friend always looked on the bright side of life and he changed the life of many Anangu due to his expertise and knowledge of architecture. Paul also brought good humour with him wherever he travelled and whoever he worked with. I was truly sorry to hear the sad news of my good friend.

Yami Lester, Anangu Elder, APY Lands

AN INCORRIGIBLE UNIVERSALIST and generalist, I had always been sensitive to the importance in Paul’s work of the particular and the specific. The conditional and the circumstantial were everything. He once devised an exercise: give the students an aerial photograph of a site and get them to work out the exact day it was taken. What do you look for? People (how many and where); motor vehicles (of what kinds, in what numbers and travelling in what directions); grass and trees (what colour and what density of foliage); shadows (what direction, intensity and length); and ocean (apparent depth, extent of chop and wave direction). The students got very, very close and learned to see the always-already-there as pointing to something that is not-there-yet.

Design is this drawing out of the always-already-there, propensities conjugated to make a place: soft ground + raised ledge + windbreak + shade + prospect + firewood + water = good place to camp. Now the designer assumes the attentiveness and modesty of a tracker who construes situations on the basis of traces. Design is not to be invented but found. Recasting it within the common sense of a systematic, rigorous pragmatics was always going to interest students accustomed to the concocted, mysterious inevitability of never quite being able to get there.

These propensities are all a matter of concrete quantity. Nothing – no client, brief, site, material, product, concept, system, pedagogy, administration – can be taken for granted. Everything is equally subject to the same, precise interrogation and no claim or pretense is uncontestable. This sense of determined inquiry was the rigor of a process. It was also the calibre of a man, keeping the ambition modest through the long haul. It is what made him empathetic and impressive, and – especially when joined to a sense of humour attuned to the ridiculous – it is what made him so engaging and charismatic.

Michael Tawa, Professor of Architecture, University of Sydney

People are not the problem. We’ve never found that. The problem: poor living environment, poor housing and the bugs that do people harm. The common link between all the work we’ve had to do is one thing, and that’s poverty … It’s been the actions of thousands of ordinary human beings doing – I think – extraordinary work, that have actually improved health, and, maybe only in a small way, reduced poverty.

Paul Pholeros in his inspiring 2013 TEDxSydney talk ‘How to reduce poverty? Fix homes’

PP: LOOKER, LISTENER, TEACHER, learner, leader, artist, Australian.

PP loved Australia, the country, the people who lived in it and respected it, and whoever wanted to learn about land and country, against a wealthy society’s lazy habits. He learned and taught about Australia by going bush, quietly listening and looking, really, really close, like it was all a great music, a huge art. As we are still trying to learn.

You never quite knew if PP had the answers (he did) or wanted you to find out for yourself. It was the questions that mattered.

PP’s great slide show: 12 days in the bush, 12 campfires. That’s it.

‘What’s the best possible first-year course, Doc?’

‘That’s easy. Walk back to here from the Rock. They’ll learn everything they need to know.’

PP & Mongrel Design: architect, traveller, storyteller, conceptual artist, joker, punster: ‘Mongrel Travel puts the tale between your legs.’ So much work, so many jokes. Don Lane and Lawsie on the radio, Van the Man on cassette, Duchamp and nonstop jokes about political idiocy and human folly. Cartoons and Jimmy Buffett, solid: ‘I got my Hush Puppies on – I guess I never was meant for glitter rock ‘n’ roll.’

PP’s Weet-Bix detail. On tender documents, an obscure spec. tucked away in plain view: ‘Footings of crushed Weet-Bix to future detail’. Wait to see if the unwary builder queries ‘that footing detail on page 6’. Always provocations: a test, a contest, a deadly serious game, always for keeps, a lark. Learn all that.

A messianic character, a man of love and charity and hilarity; the biggest bloke any of us could ever know, or be. Our parents loved him and our kids loved him and his jokes, and he loved us all back with his time and kindness. Vale PP.

John Roberts, Lecturer (architecture), University of Newcastle

BEFORE PASSING THROUGH the threshold of the office each day, eighty steps had to be ascended. Carefully meandering up the steep site, each step climbs up into the trees and further away from the road. With each step my mind would become increasingly present, oriented by what surrounded, honoured by the careful placement and self-built care of his creation. Paul designed the journey to a place with as much importance as the place itself. The final ten or so steps to the office transitions from timber to natural rock to timber again, forcing a change in rhythm and pace. In these final steps, I am guided into the shed by Paul’s voice.

We were greeted always with a warm smile and unwavering positivity, I’d say ‘Good morning Paul, how are you?’ ‘I’m brilliant!’, he’d respond. And with a forced clarity, present for a day’s work, I am neither a cog in the wheel or totally unique, but contributing to the evolution of the architectural practice and progress of Healthabitat.

Before my eight years in the shed began, Paul had crafted an architectural practice out of a commitment to people and place. Paul had employed and mentored many young architects, namely Justine Hill and Adriano Pupilli. For over a decade Justine balanced Paul’s great vision and matched his acute attention to detail, hand drawn rigour, robust analytical mind and egoless patience. Adriano brought computer drawn efficiency, technological know-how and an activist’s impatience to the office. And then me, somewhere in between the hand drawn and computer generated, passionate and patient, measured and impulsive.

Paul ensured that we not only shaped the practice but contributed to advancing the work of Healthabitat as guided together with Directors Stephan Rainow and Paul Torzillo, managed by Karin Richards, whose voices resonated through the office daily. Paul’s practice in life and in work ensured we were always connected to a lineage of great minds and extraordinary experience, to place and to people. Leading from behind, he believed connecting us to each other connected us to ourselves – and that this was core to the job of an architect.

Heleana Genaus, former employee of Paul Pholeros Architects and communications manager of Healthabitat

* APY Lands: Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara is a large Aboriginal local government area located in the remote north west of South Australia