A ‘school’ is defined as an organisation of scholars ‒ in this case, architects ‒ whose interests and ideas coalesce around particular philosophies. The formal etymology of the term ‘Sydney School’ begins in 1961 when the late Bruce Robertson organised a travelling exhibition, “15 Houses by Sydney Architects”, at the Blaxland Gallery housed in Farmer’s department store, which was then moved to the Museum of Modern Art of Australia (MoMAA), Melbourne as Modern Sydney Domestic Architecture.

The photographic exhibition included the architects and firms John Allen and Russell Jack, Ross Thorne, John James, Bill and Ruth Lucas, Ian McKay, AncherMortlock and Murray and Peter Muller. Others included in the exhibition were Bruce Rickard, Harry Seidler, Andrew Young, Max Collard and Guy Clarke, Neville Gruzman, Bruce Robertson (curator), Peter Kollar and James Kell.

A review by architect Neil Clerehan appeared in the Royal Victorian Institute of Architect’s Small Homes Service section of The Age1. “The first thing to strike anybody with more than a passing interest in houses is their unfamiliarity,” Clerehan wrote. “They could not be local [Victorian] houses.

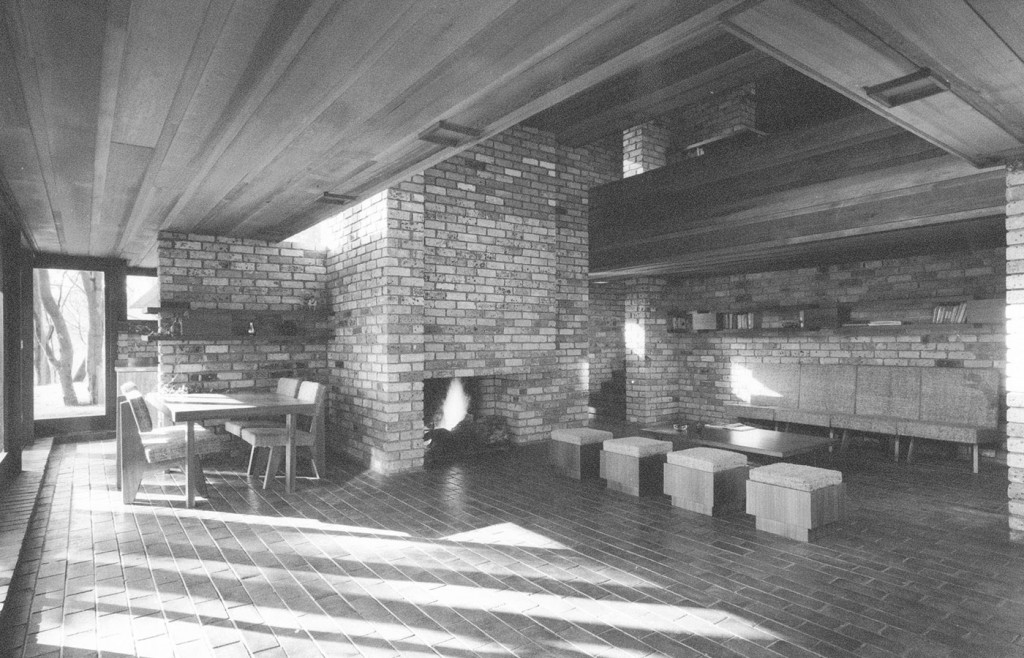

“Sydney has always offered better sites, bigger trees, steeper slopes and full circle views. […] Everyday Sydney houses are very different from the Melbourne equivalents.” Clerehan then turned to regional differences observing, “Now there seems to have developed in New South Wales a distinct style. The houses on display will appear foreign to most visitors to this exhibition. […] Whereas Melbourne houses by comparison preserve tight trim shapes and sit immaculately on their pancake-flat blocks, the Sydney houses ramble everywhere between the eucalypts and poke windows at views or walled courts. They use heavily beamed frames, rough brickwork, varying roof levels, screens and huge stone fireplaces.”

Clerehan identified a “distinct style” responding to the Sydney basin’s topography and established the premise of a Sydney School, which was quickly adopted by Milo Dunphy in a 1962 essay using the term ‘Sydney School’ and nominating members including most of Robertson’s earlier picks such as Ancher, Mortlock and Murray, Muller, the Lucases, Rickard and Gruzman2. Dunphy asserts there is “…a unity of sentiment and aim” among these architects that “has now rejected self-conscious nationalism.”

By 1965, the Sydney School ruminations had entered architectural consciousness and Robin Boyd’s 1965 book The Puzzle of Architecture includes Sydney School passages suggesting a close reading of Clerehan’s original review of the Melbourne exhibition. Boyd and Clerehan were Victorian associates and key figures in the RVIA/The Age Small Homes Service. Boyd writes “a strong regional branch developed […] in Sydney where there was a sufficient number of younger architects with enough in common to constitute a school3”.

Former University of Sydney professor Jennifer Taylor (now adjunct professor at Queensland University of Technology) firmly planted the flag for the Sydney School in her 1972 publication An Australian Identity: Housesfor Sydney 1953‒634. Despite considerable criticism among scholars, Taylor’s publications continued to be the key documents in electing Sydney School practitioners5.

Professor Winsome Callister, Monash University, suggested the Sydney School was a new offering from the shop-worn Sydney/Melbourne merchandise counter6.

The Sydney School was also inspected by Professor Stanislaus Fung of the University of New South Wales architecture faculty (now at the Chinese University of Hong Kong). Fung regarded the Sydney School as no more than a notion, arguing, “…the confidence in the existence of the Sydney School is disproportionate to the amount of serious study given to the subject7”. Is the Sydney School a certain group of architects united by principles; is there a series of buildings that could be said to represent the expression of these principles; and finally, Fung asks, is there a Sydney School style illustrating consistent architectural qualities?

Not every architect tagged as one of Robertson’s Sydney School wished to be a member. Peter Muller observed in a 2014 interview:

“Academics, scholars and journalists very much need to classify everything, [and] labelled those Sydney architects who use natural materials such as wood and stone, like myself, [as] organic architects and members of the Sydney School as if we were a coherent group. We were site specific to a certain extent but certainly not organic in the sense I’ve […] described.8”

Muller is dissatisfied with being identified as a practitioner, arguing that after spending several days studying the site, “[…] the design process followed after negotiations with the client because I had to know their limitations and their requirements. And then the design project was left to emerge intuitively.” That is, this takes place without regard to formal principles one might associate with a school.

Ken Woolley is also anxious to avoid membership. “A number of times I’ve said it didn’t exist,” he emphatically stated in a 1986 interview. “In the sense of a group of people getting together to form a school or even to recognise that there is one […], it didn’t exist.9”

John James reveals how membership in the group was arranged. James and Sydney Ancher had been key figures in the Melbourne tour. James writes, “I was part of the Sydney Timber-and-Bush School along with Peter Muller, Russell Jack and others. I suggested to Jennifer Taylor that we all meet and see if we could discover what inspired us. This we did at her house in the summer of 1981 [sic.].”

He continues: “It was an extraordinary meeting. We all noted that though we knew of each other, we seldom met; neither socially, nor for business, nor did we spend much time running around looking at each other’s houses. Yet together we created a common style, now called the Sydney School. The only things we had in common, and that we all agreed stimulated our creativity, was sandstone rocks and angophoras.10”

Following the patterns of James’s reminiscences, Muller suggests a far-sighted alternative to the Sydney School. “I call my approach ‘site specific’. I consider that a few Australian architects in the 1950s and 1960s, working alone, seldom in communication with each other, adhered to an architectural idea that I called site specific. By this I mean they gave due consideration to the nude physical attributes and the location of each site before commencing the design process. This attentiveness to retain [the] integrity of the site almost necessarily implied the use of natural materials such as timber and stone.”

Muller, of course, is identifying a regionally adapted architectural methodology. Since the 1960s the Sydney School hypothesis has been diluted by an inclusive ‘regionalist’ philosophy popularised by the well-known Columbia University scholar Kenneth Frampton and others that seek to “…foster connectedness to […] place and […] be a response to the needs of local life, not in spite of global concerns and possibilities, but in order to take better advantage of them. […] It should open up possibilities for understanding where and with whom one lives. It should encourage awareness of local climate and the changing of seasons.11” There is room within this “Regionalism”, as James suggests, for “sandstone rocks and angophoras.”