table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

- Front verandah, Sydney Hospital, 2015.

THE JACK ARCH: its origin and use in NSW

Conservation architects Sean Johnson and Ian Stapleton discuss one of the most important design elements of 19th century architecture: the jack arch.

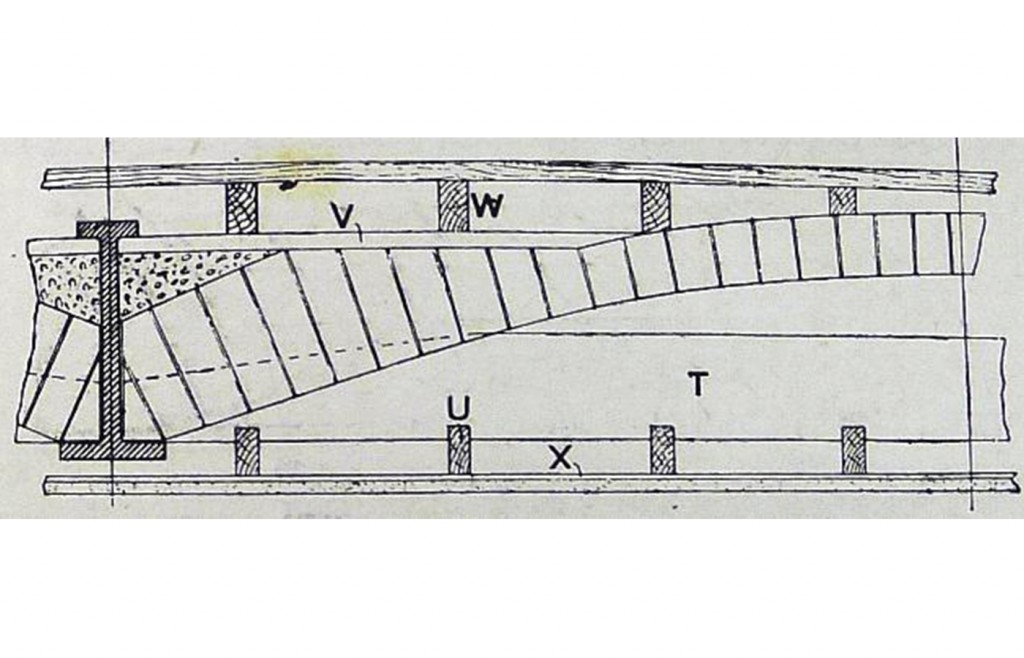

Used throughout the 19th century for its incombustibility and strength, the jack arch was a widespread form of floor construction. It was not a flat arch in the US sense of the term, rather, the jack arch consisted of shallow brick or concrete vaults spanning between iron or steel joists. This composite construction was often concealed between timber flooring and plaster ceilings, but sometimes it was intentionally exposed, often in verandahs and arcades, with satisfactory aesthetic results.

The jack arch system, an innovation of the mid 1800s, was widely used in New South Wales, however, it was the result of a long evolution that started in the 1790s in England. After a series of disastrous fires in timber-framed multi-storey mills, William Strutt built the first ‘fireproof’ mill in Derby; it was constructed of brick vaults spanning between shouldered timber beams, in turn supported on cast-iron columns. An attempt was made to protect the timber beams by encasing them with metal sheeting. The Benyon Marshall and Bage Flax Mill, built in Shrewsbury in 1796‒1797, was the first fully iron-framed multi-storey building. It used cast-iron beams with similar wedge-shaped bases angled to provide a springing point for the brick vaults.1

From these evolved the flanged beams we are familiar with today. This system became widely used in public buildings, and especially in “mills, warehouses, sugar factories and other buildings, where great weights have to be stored.”2 It was also used in private houses, for example Queen Victoria’s holiday home Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight, UK, by Thomas Cubitt, built between 1845‒1851.

The jack arch was for many years believed to be fireproof, but the bottom flange of the iron joists remained exposed to heat and by the late 19th century it was realised that this was a fatal flaw. Rivington’s Notes on Building Construction: a book of reference for architects and builders, and a text-book for students, stated in 1884 that “iron at one time held a very high place as a fireproof material, but it has of late years been found to be untrustworthy”. Paul Hasluck, in the 1906 publication Iron, Steel and Fire Proof Construction, referred to a large warehouse with “so-called fire-proof floors” composed of brick arches between iron girders and cast iron columns, which was “destroyed by fire within an hour in Berlin a few years ago”. 3

Despite this, the jack arch continued to be used in New South Wales well into the 20th century. It usually consisted of unreinforced lightweight coke concrete vaults cast on curved corrugated iron sheets spanning between iron beams: a 19th century version of the familiar Bondek slab. According to architectural historian Miles Lewis, this system was invented in 1848 by the British engineer James Nasmyth, and its first use in Australia was at the Old Treasury Building, Melbourne, designed by J.J Clark and built between 1858‒1862.4 By the 1880s, a heavier gauge corrugated iron with deeper ridges specifically designed for jack arches was imported from Germany and employed here.

The first use of the jack arch in Sydney was at James Barnet’s General Post Office (GPO), which was built in stages between 1866-91. Here the extremely flat, lightweight concrete arches were cast on formwork and generally concealed behind floors and ceilings, however, shallow plastered vaults are exposed at basement level. During the recent conversion of the GPO, the structural engineers were initially doubtful about the strength of the arches, especially if they were to become wet in the case of fire. They loaded an arch with sandbags, however, it was found to be remarkably stable and no further strengthening was required.

Barnet used jack arches again throughout the floors of the Lands Department Building, the first stage of which was built during 1876–1881. They were generally hidden above plaster ceilings but were exposed on the upper floor. Smooth plastered concrete vaults were also exposed to view on the ground floor of Barnet’s Callan Park Asylum in 1876‒1885.

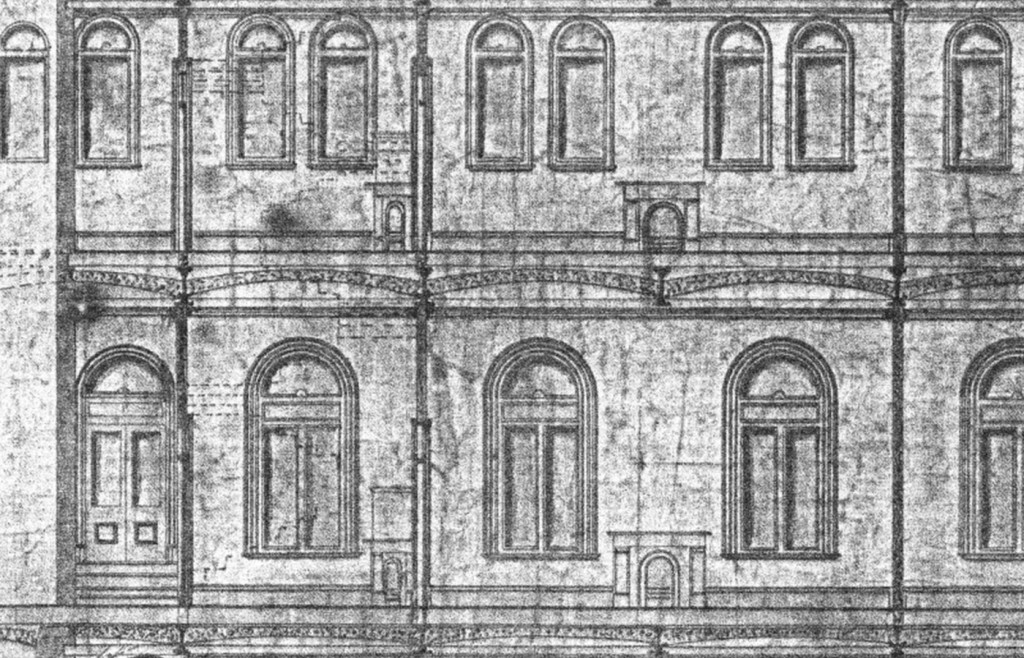

Corrugated vaults were adopted in Australia more than in the UK. The system was taken up widely by other Sydney architects: Thomas Rowe used corrugated jack arches in the verandahs of the Sydney Hospital 1880‒1894, while George McRae used them on the ground and first floors of the Corn Exchange building, 1887. In the Queen Victoria Building, 1893‒1898, McRae used brick vaulting spanning steel beams.

Barnet’s successor as Government Architect, Walter Liberty Vernon, continued the jack arch tradition into the 20th century in his additions to the Australian Museum (built 1897‒1910), and at Central Station (1904‒1908), where corrugated jack arches were used for strength and solidity, rather than fireproofing, throughout the lower level under the paved forecourt areas.

The jack arch was an economical way of building a strong, non-combustible floor structure that could be left as a visible ceiling with a satisfying structural logic. It was largely superseded by the introduction of thinner and more fire-resistant concrete-encased steel and reinforced concrete floors later in the 20th century. However it remains an expressive and strong form of construction that still occasionally reappears, for example in SigurdLewerentz’s brick St Peter’s Church, Klippan, Sweden (1963‒1966) and more recently at the RavensburgKunstmuseum by Lederer + Ragnarsdóttir + Oei.5 Perhaps it’s time to put the arch back into architecture?

Sean Johnson and Ian Stapleton are conservation architects and partners of Clive Lucas Stapleton and Partners.

FOOTNOTES

- Alan Ogg, Architecture in Steel, RAIA, 1987, p.58.

- Rivington’s Notes on Building Construction: A book of reference for architects and builders, and a text-book for students, London, 1884, p.368.

- Paul N. Hasluck, Iron, Steel and Fire Proof Construction, Cassell& Co., 1906, p.99.

- Paul N. Hasluck, Iron, Steel and Fire Proof Construction, Cassell& Co., 1906, p.99.

- Architectural Review, 9 September 2013.