table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

Something Fishy

In 2015 Kevin Liu and Andrew Daly were jointly awarded the David Lindner Prize for their research proposal focusing on the Sydney Fish Markets and its role in the redevelopment of Sydney’s urban environment. Andrew Daly summarises the impetus of their research and findings on the road to understanding authenticity and experience in the city.

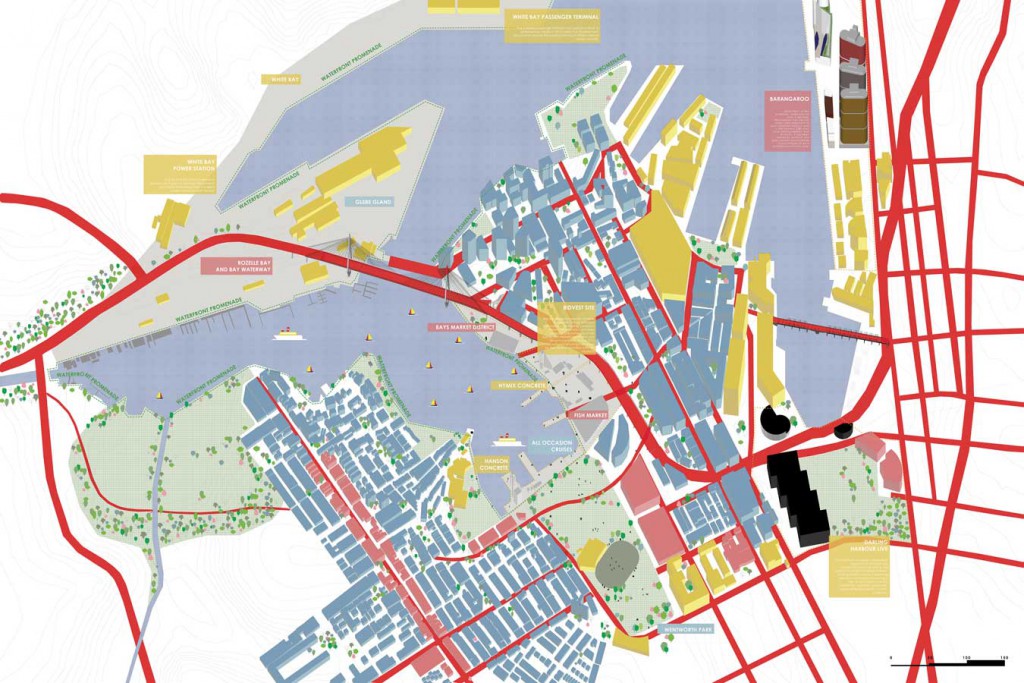

The David Lindner Prize was an opportunity to develop a research project that could inform the conceptual agendas of an emerging practice. Initially our interest lay in exploring hybrid development methodologies sensitive enough to integrate non-residential programs into the densification rationale of the inner-city, particularly given the increasing pressure for residential mixed-use developments. The Bays Precinct and the Sydney Fish Markets (SFM) struck us as a particularly salient opportunity to explore bigger concepts of the project of the city itself in light of their imminent redevelopment, focusing around two key concepts: authenticity and experience.

We started as urban-archaeologists, piecing together a picture of Barangaroo’s procurement to understand the status quo. Presented as a graphical timeline, a fragmented picture of major projects in NSW emerged, mapping out recurring individuals, events, governments, planning instruments and regulatory changes that make up Barangaroo’s DNA. By tracing out this wider context we sought a simple understanding of the likely pressures on the upcoming development of the Bays Precinct. It seemed simplistic to believe that the Bays Precinct and the SFM would be exempt from an equally complex web of influences, but what also emerged was the feeling that contemporary city-making and urbanism have some thorny issues that remain unaddressed, hidden under the banner of progress.

The relationship between the commodification of our cities into consumable leisure activities and the increasing homogeneity of architectural types employed to this end encapsulates problematic notions of progress, experience and authenticity in how we conceptualize cities. Increasingly constructed as choreographed and consumable experiences for the leisure of its inhabitants, we found strangely productive parallels between contemporary urbanism and theme parks – a relationship between leisure-consumption and profiteering that conspire to produce a veneer of authenticity that obfuscate development windfalls. Depending on your point of view, it’s either deplorable or seductively euphoric.

Experience and authenticity underlie contemporary city making. There is a unifying question for everyone involved: how can we create equitable and sustainable cities that manage the negative aspects of density in a way that maintains continuity with the cultural and social practices that provide that elusive quantity – authenticity? Our research started with this possibility: that the SFM, sitting at the nexus of a number of industries (primary, food processing, retail, tourism, logistics) is a resilient site capable of being developed while maintaining its experiential authenticity. However, like a theme park, in the contemporary city the line between authentic and simulated experience is blurred to the point where it is unclear whether it exists – or matters.

There is a necessary suspension of disbelief at the SFM that allows us to willingly ignore that choreographed relationship between authenticity and functionality. Our desire for an authentic experience of burly fishermen on a rugged harbour foreshore mending fishing nets seems at odds with fish delivered by the truck-load, of picturesque but non-accessible wharves, of a dysfunctional carpark where tourists stand helplessly by while psychotic seagulls make short work of unsuspecting sashimi. Does, can and should authenticity really matter in the contemporary cultural landscape?

The concept of amenity in contemporary development, particularly in relationship to public space, is a key battleground where authenticity, experience, leisure-consumption and simulation play out. As a bargaining chip, a quantifiable definition of amenity seems to be the sole remaining currency in ensuring long term benefits like parks and public spaces are there to produce some public benefit alongside the profit of private interests. Increasingly, amenity is a regulated concept, particularly in relationship to residential developments. The SFM also presents interesting challenges here – noise, odour, traffic – begging the question is the site even appropriate for redevelopment?

That the SFM itself isn’t really a working harbour but a simulated and choreographed experience sits at the heart of its attractiveness and bears further examination. Suggestions of moving the markets elsewhere in the Bays Precinct are somehow both practical and disappointing: logical in solving problems but at the cost of an opportunity to diversify concepts of amenity and urban regeneration. By reducing amenity to quantifiable traits over experiential qualities, a future city that takes advantage of both new and continuing practices and experiences is limited by the regulatory framework established for it. What we find regrettable is that the types and forms of amenity that are acceptable have taken on a homogeneity and expectedness. The processes of recent public procurement have so challenged our faith in the possibility of what we want translating into what we get, instead we are happy – lucky – to be getting something as straightforward as a park. Somehow scrounging back this level of public outcome is seen as a watershed moment.

The play between authenticity, experience and simulation is at the heart of any development of the Bays Precinct and the SFM. Recent concepts, reports and studies recognise this important common ground between stakeholders: the SFM is a place reminiscent of Sydney’s working harbour history and its ongoing function as a working fish market is a key outcome of its future for both its stakeholders and the public. This is also the SFM’s greatest challenge. In a society where the lines between historical authenticity and simulated experience are increasingly part of a commodified procurement process, maybe to maintain that authentic feeling the SFM needs to be little more than a fish-themed mall. Maybe the most authentic solution is to get a giant Frank Gehry fish-sculpture, give in, stop worrying and love the bomb. We hope not.

Andrew Daly

Partner, TYP-TOP Architecture