table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

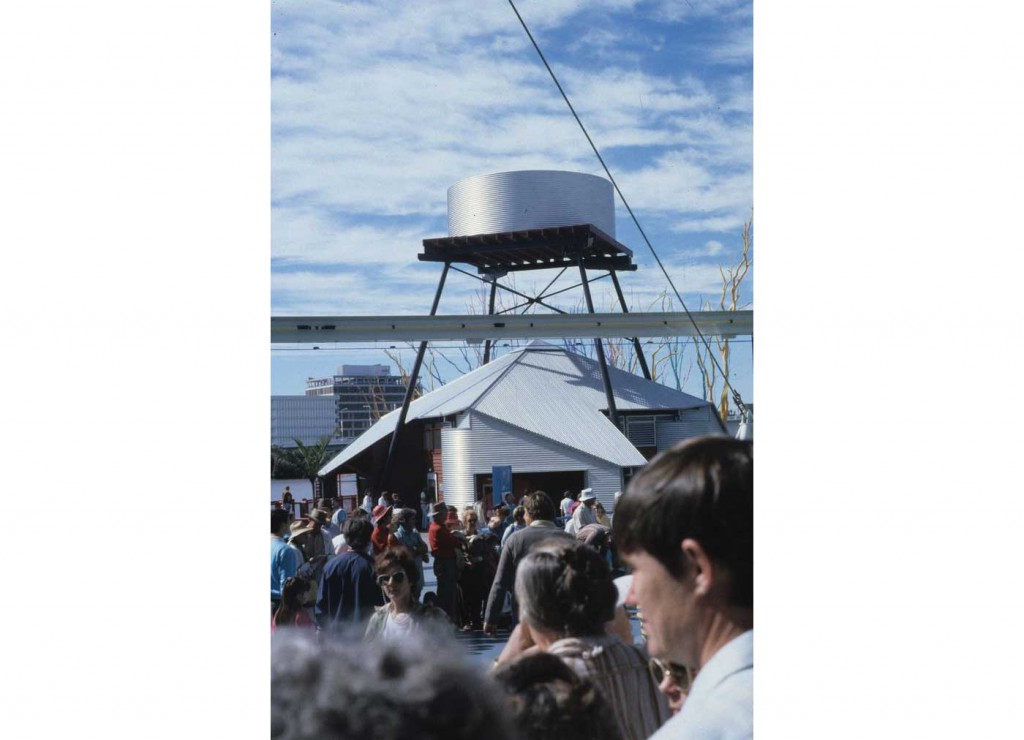

- Australian Pavilion at World Expo 88, Brisbane, Ancher Mortlock and Woolley with graphics by Ken Done. Photo: Jitdhikorn.

Leisure in the Age of Technology

Brisbane’s World Expo 1988 depicted our future as a technology-based utopia with increased leisure time and holiday pursuits, Andrew Nimmo takes a reality check 28 years later.

Back in 1985 I was a student working at Hulme and Webster Architects in Brisbane. One of the more interesting projects that I worked on was the World Expo 88 Information Kiosks completed in association with Rex Addison. They were shiny tin and timber structures showing off the local vernacular, all be it through Addison’s idiosyncratic reinterpretation.

Leisure in the Age of Technology was the theme of Brisbane’s World Expo 88, the highlight of Australia’s bicentennial celebrations. The event did much to change Brisbane. It attracted 15.8 million tourists 1(double the expected numbers) through a city that for most was seen as little more than the seat of government for the Great Barrier Reef. It introduced outdoor dining, which until then had been outlawed for hygiene reasons. Nightlife started to flourish beyond the sleaze of The Valley’s “Moonlight State” brothels and gambling dens. For the first time people walked (instead of driving) across the Victoria Bridge, over the Brisbane River, from the city to the Expo site in South Brisbane.

Most importantly, it put in train the redevelopment of what is now known as South Bank, which continues the leisure theme of the Expo from 27 years earlier. It cemented forever the city’s rediscovered relationship to the Brisbane River that was initiated by Robin Gibson’s Cultural Centre (from 1982) and Harry Seidler’s Riverside Centre Tower (1983-86).

Culturally Brisbane and Queensland were ready for change. Premier Jo Bjelke-Petersen had already been removed in favour of the mild-mannered Mike Ahern, with the unfolding events of the Fitzgerald Enquiry straddling the Expo celebrations. Brisbane and Queensland were never going to be the same again.

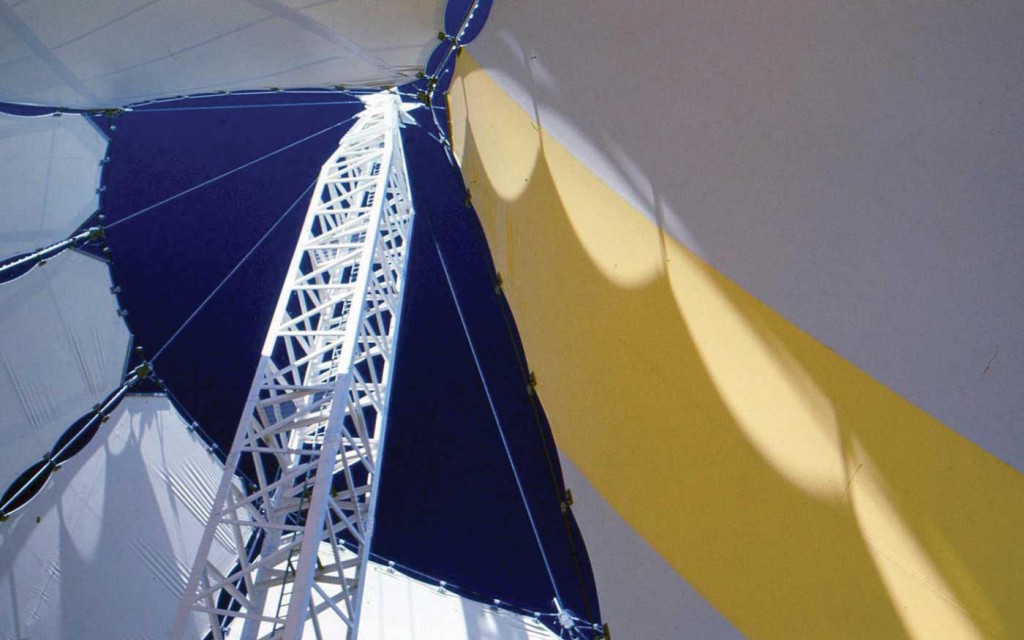

The Expo was also a chance for Australian architects to shine on the world stage. The Australian Pavilion, symbolising the colours of Uluru (then Ayers Rock), surf and rainforest was by Ancher Mortlock and Woolley and featured a funky 3-D Ken Done super graphic spelling out A-U-S-T-R-A-L-I-A. Robin Gibson and Partners designed the Queensland Pavilion and Denton Corker Marshall the Queensland Newspapers Pavilion. This was all under a respected master plan developed by Bligh Maccormick 88, (a consortium of Bligh Jessup Bretnall – a precursor to BVN – and James Maccormick, (Maccormick designed the iconic Australian Pavilions at the World Expos in Osaka 1970 and Montreal 1967)). The theme of leisure found expression in the fanning shape of large fabric and mast structures that snaked their way through the site providing much needed relief from the Queensland sun. They were playful forms that were transformed each night with colourful light projections.

It all had the feeling of Disney’s Tomorrowland. There was a monorail, now relocated to SeaWorld on the Gold Coast (completed a few months before Sydney got to regret having one). Upon entry, glowing humanoid robots greeted visitors in 32 languages and parades featured computer-operated diorama floats. In the Victorian Pavilion, a robot demonstrated domestic chores such as ironing, while the Japanese Pavilion featured 3 metre wide by 1.7 metre high HDTV (high-definition television) broadcasting Japanese scenery. They were described as “the visual medium of the future”.2 The US pavilion included a virtual golf driving range. The Swiss pavilion featured “text internet” and a ski slope made of artificial snow – very novel in Queensland. Most took the leisure and technology theme to heart.

Strangely enough the most popular pavilion was New Zealand, with its animated Footrot Flats show and glow worm cave, which sometimes took up to six hours to gain entry. After six months of partying, Expo 88 closed with a performance by The Seekers of their hit song, The Carnival is Over.

After the Expo packed up and moved on, there was much discussion on how the site should be redeveloped. The original River City 2000 development plan had a Barangaroo-esque flavour to it, (complete with a casino, upmarket apartments and a World Trade Centre), with development consortiums driving proposals and the public squeezed out of decision-making. But the public had a taste of riverside public space and did not want to give it up – they wanted the “People’s Park”. Under increasing public pressure, eventually the Queensland Government formed the South Bank Development Corporation under the chairmanship of Sir Llew Edwards. They released a new plan for comments and consultation late in 1988 – it did not include a casino.

Plans for the South Bank continued to evolve, partly in response to failed endeavours, stalled investment, changing governments and changing priorities. In 1996 a new board shifted the focus further toward design excellence. John Simpson was appointed as master architect and a design advisory panel formed to assess all proposals. In 1997 Denton Corker Marshall were engaged to prepare a new master plan which forms the structure of what is now there. They also designed the beautiful kilometre long Grand Arbour of curling steel columns covered in flowering bougainvilleas. All that remains of the Expo is the Nepal Peace Pagoda, which was moved to a riverfront location at the conclusion of the Expo and remains as an official souvenir. (Skyneedle, the 88 metre high light tower, was procured by local celebrity hairdresser Stefan and relocated to Stefan HQ in South Brisbane – despite catching on fire twice, apparently due to birds chewing on the lighting, it will now form the centerpiece of the proposed Skyneedle Apartments.)

One of the highlights of South Bank now is the city’s beach, called “Streets Beach” (as it is sponsored by the ice-cream company) – 2,000 square metres of free-formed concrete surrounded by 4,000 cubic metres of pristine sand. It is here on the Clem Jones Promenade that the wet and semi-naked come face to face with the cocktail set attending shows at the neighbouring Performing Arts Centre. It is urbanism as only Brisbane can do it.

Again, there are many similarities here with Barangaroo and the headland park, where public leisure space appears controlled by corporate interests. As Louise Noble wrote in her excellent article in Architecture Australia (September 2001): “The ambiguities between public and private space are inherent in a project conceived in the age of corporatized infrastructure. Is it a democratic space? Could it be described as the ‘People’s Park’?”3

Leisure in the Age of Technology, at the time this seemed an insightful and relevant theme. From the Celebrate 88 website, “Technology and the sciences have been common themes for 20th Century Expositions, however, the marriage of Leisure and Technology, was, for World Expo ‘88 a world-first – signifying a new prosperous age of man – where leisure time became an increasingly important part of each day’s living.”4

What were we going to do with all this spare time released to us though the great liberator of technology? Some may say that technology has enslaved us, but it certainly has not liberated us to a world of leisure. We are just as busy working today as we were 27 years ago. Technology has just given us more things to fill our time with.

It turns out the theme of leisure was more about promoting Queensland as a place to invest and as a tourist destination to the Japanese. In 1988 the Queensland Government was very pro-Japanese investment. It is very interesting to note that at the time there was significant suspicion in some quarters in Queensland about the amount of Japanese investment, (not dissimilar as there is today with regard Chinese investment.)

In the Queensland Pavilion leisure was presented as an escape from technology into the natural environment.5 In 1988 during Japan Week the Courier-Mail ran a feature section that focussed on the broader aspects of Japanese culture including a work-obsessed and leisure-deprived society yearning for an understanding of other lifestyles and wanting to finally enjoy the fruits of their labour. Where better to do that than Queensland?

Nearly 30 years after Expo 88, it is interesting to ponder on how leisure has made its way into our modern lives. In Brisbane, the legacy is real – where that greatest symbol of Australian leisure – the beach – has been recreated within the heart of the city.

Beyond this, there is definitely a shift in how the markers of leisure are incorporated into modern architecture – especially the work place. Work is no longer only conducted at the workstation or the conference table. We have break-out-spaces with ping-pong tables, beanbags and swings. Kitchenettes have transformed from a dank and smelly cupboard off the corridor to a casual bar – complete with coffee machine, flat screen TV, lounge chairs and a glass-fronted fridge. This is also where meetings can occur. Larger corporations have their own gyms, childcare centre, cafes, and roof top urban farms. It is all about making the workspace look less work-like. Our surrounds might suggest resort, but we are still working just as hard.

Andrew Nimmo

Director, lahznimmo architects

Chair, Editorial Committee, NSW Chapter

Adjunct Professor Faculty of Architecture,

Planning and Design, University of Sydney

FOOTNOTES

- http://www.expomuseum.com/1988/

- Sanderson, Rachel ‘Queensland Shows the World: Regionalism and Modernity at Brisbane’s World Expo ‘88’, Journal of Australian Studies (pp.65-75) Richard Nile (Ed.), Issue 79 “Rezoning Australia” (2003)

- Louise Noble, South Bank Dreaming, Architecture AU, September 2001 http://architectureau.com/ articles/south-bank-dreaming/

- http://www.celebrate88.com/aboutcontents.html

- Rachel Sanderson, Queensland Shows the World: Regionalism and Modernity at Brisbane’s World Expo ‘88, Journal of Australian Studies (pp.65-75) Richard Nile (Ed.), Issue 79 “Rezoning Australia” (2003)