table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

- Bondi Beach, 1900. Tyrrell Photographic Collection, Powerhouse Museum.

Coastal Leisure

The Australian beach is a complex cultural landscape with a rich history of outdoor pursuits, tourism, mass culture and community activism. Scott Hawken takes a closer look at the architectural heart of this iconic site, the beach pavilion.

In the early years of the 20th century the beach evolved as a defining Australian cultural landscape. For a now well established colonial population, the outback represented an unforgiving and alienating landscape of inland battlers of toil and hardship, in high contrast, the beach signified a new culture complete with aspirational figures found in the heroic life saver and the blonde, muscled surfer. The foundation site for this cultural mythology is without a doubt Bondi: the location of Australia’s first life-saving club, the legendary Icebergs, and the epicentre of the surfing and surf swimming craze.

Although there is certainly a Bondi Beach mythology, this monolithic image masks a careful understanding of change. Far from being timeless, Bondi has witnessed at least two waves of change since the turn of the twentieth century and is about to experience a third ($38 million dollar upgrade) with designs currently on the drawing board for a revitalised Bondi Pavilion and surrounding park. Constructed in 1928 during the interwar phase, Bondi Pavilion originally served as a practical monument, housing numerous changing sheds, for the flourishing mass culture of “surf bathing”. This golden age lasted several decades before the pavilion lost relevance in the more casual post-war period. In the 1970s local grass roots activism saw the institution reborn as a community based complex, idealistic, authentic, and distant from the aspirational glamour of the pavilion’s early years. These phases of change are emblematic of the politics of coastal leisure that persist today. Over the last century Sydney’s beaches have been a battle ground for local issues as much as they have been sites of mass tourism.

Relatively recent listings of Bondi Beach as a cultural landscape and on state (2008) and federal (2008) heritage registers acknowledges its value as one of Australia’s most loved places. It is certainly popular with 14 million people visiting the beach each year. For most, the beach is experienced as a site of summer pilgrimage, much as it was when Bondi Pavilion was first built. During the 1920s and 1930s beach pavilions like Bondi were established on beaches in Sydney and along the NSW coastline. These temples of hedonism were, like architectural chrysalises, places for reappraising white Australian bodies as they emerged from the modest and stiff Victorian era to discover the bright Australian sun. This transformation inattitudes was striking. Prior to 1902 swimming during daylight hours was illegal and many beaches were inaccessible. It was only through activism in the early twentieth century that public access to Sydney’s beaches and their waters, was achieved. In the early years attire was very conservative by today’s standards. At Bondi after changing from your stiff street clothes into a concealing swimsuit you were able to walk to the beach in a “modesty tunnel” that emerged in the sands of the beach. These tunnels were demolished for defensive reasons during the Second World War.

Beach architecture, such as Bondi Pavilion, is a clear reminder of the emergence of beach culture in the first decades of the 20th century when as many as 50,000 people came to visit Bondi on a summer’s day. The Bondi Pavilion was one of many built during the interwar period. Some have been demolished such as the South Steyne Manly Surf Pavilion, a design that followed its difficult cliff-side site to great effect, with an expressive L-shape plan and a sleek modernist design that won its architect, Eric W Andrew, a Sulman Award in 1939. Thankfully many others remain such as the Cronulla Beach Surf Pavilion in interwar stripped classical style (1940); Bar Beach Surf Pavilion in the Spanish Mission and Art Deco styles (1933); Manly Cove Pavilion in Mediterranean style; the Balmoral Bathers Pavilion (1928) in “Moorish” Mediterranean style and restored for adaptive re-use by Alex Popov in 2000; Newport and Freshwater Beaches in Mediterranean style; The Entrance Surf Life Saving Clubhouse (1936) in Mediterranean Style and the North Beach Bathing Pavilion (1938) in Wollongong built in the Interwar Functionalist style. In Wollongong a decade long project involves refurbishing a whole stretch of coastline sea walls and heritage architecture in a project known as The Blue Mile. The Blue Mile project has resulted in a new appreciation of beach heritage. For example the North Beach Bathers Pavilion was heritage listed after an outcry over an insensitive two storey development proposal. It has subsequently been carefully restored for adaptive re-use by Wollongong City Council and Conybeare Morrison in a complex and time consuming operation that required the replacement of the building’s foundations.

Of-all-the 1920s beach pavilions, Bondi is the largest, being the size of a small city block. Built in 1928 after a design by Leith C. McCredie of Robertson Marks Architects, the building was conceived as a shining City Beautiful monument fronting the sublime Bondi Beach and sited in the centre of an extensive landscaped area with a promenade and a new encircling road called Queen Elizabeth Drive. The Mediterranean style of the building, common to interwar beach architecture of the time, shows the influence of the University of Sydney’s Prof Leslie Wilkinson who promoted such stylistic concepts with his belief that they were more suitable for the local climate, evident in the light stuccoed walls, window shutters to shade the bright summer sun while filtering breezes, and the use of arcades and columns to make architecture more open and permeable for outdoor living. The Spanish Mission style, also common during the interwar period, was closely related to the Mediterranean style. It referenced the glamour of Hollywood, California and was favoured by many of the well to do of the time.

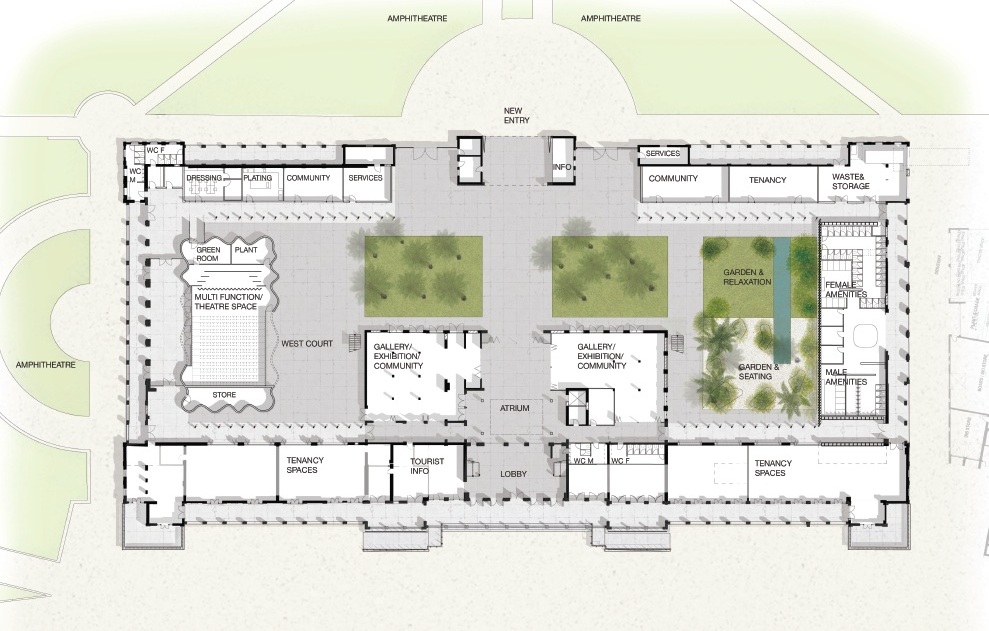

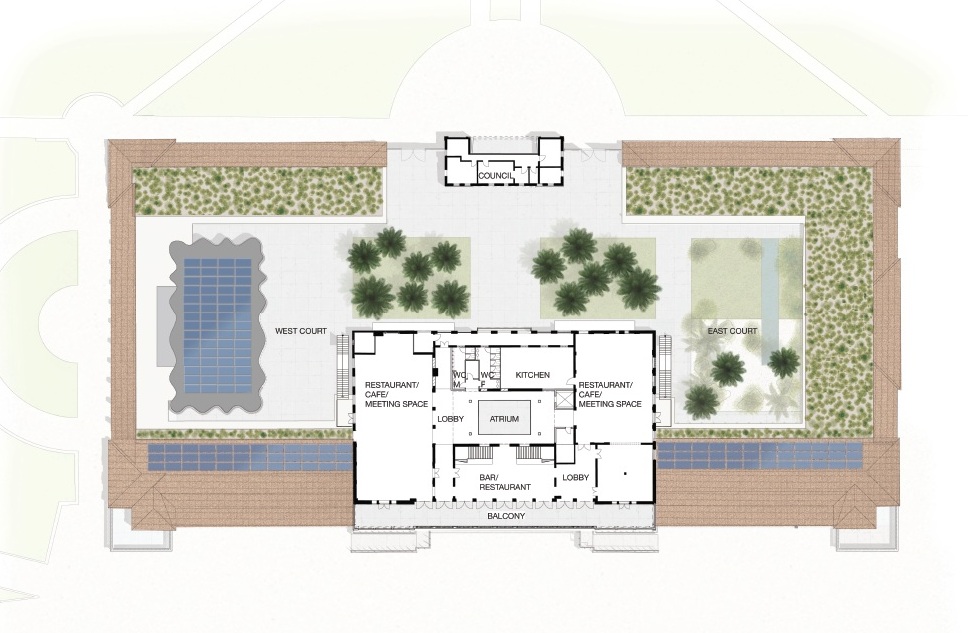

The economic sustainability and physical condition of Bondi Pavilion had been a concern for many years and the proposed adaptive re-use is both a refurbishment and a rethinking of coastal culture. Peter Tonkin, of Tonkin Zulhaika Greer (TZG) Architects who is working on the project, explains that the adaption of the heritage structure will act as a new beach gateway. It will engage the pavilion with Campbell Parade through a new civic space and a strong axial structure linking cultural facilities such as a re-located theatre, art galleries, café dining and a green oasis. The cluttered elements of the current building will be consolidated and the closed nature of the building will be replaced with an easy permeability in both the north-south and east-west direction.

In contrast with other heritage projects TZG have worked on, such as their award winning adaptive re-use designs for Eveleigh Carriageworks and Paddington Reservoir, Bondi Pavilion does not have a lot of patina or texture. Coastal environments are so brutal to the building materials that constant maintenance has prevented the creation of such a patina. The old parts of the building will be refreshed with new finishes although the new materials palette will be consistent with the Mediterranean style of the building. The 1930s heritage fabric is kept and respected and new elements are placed to complement the original fabric in scale and form while being expressly modern in their design and materials. A new glass pavilion element is to accommodate the theatre in a new ground-floor location to the northern side of the pavilion. The glass will be both patterned and etched in a way to disguise the salt spray that builds up on beachside buildings and will also reflect the sky and the surrounding columns. Similarly new columns echo the rhythm of the existing columns but with striking contemporary geometries reminiscent of a paddle or slender fish fin.

The refurbishment of the Pavilion is one of several recent projects such as the new North Bondi Surf Life Saving Club by Durbach Bloch Jaggers with its extraordinary interplay of seemingly carved voids and mosaicked solids. New amenities designs and refurbishments are being constructed at both south and north Bondi, Tamarama and Bronte by Sam Crawford Architects. Each of these projects has a different form and is based on existing site structures and conditions, but shares a common material language of timber battens recycled from a demolished warehouse in Green Square. Sam Crawford’s North Bondi project promises to be an interesting green roofed architectural structure that integrates a historic pumphouse with toilet amenities into one building. (One wonders if some agreement could have been made with the surf lifesaving club to integrate the toilet’s rather than having them as a standalone building.)

The positive aspects of co-locating such amenities are evident at nearby Tamarama which has had complete makeovers by lahznimmo architects and Waverly Council. The co-siting of the toilets and the café was a controversial decision, but an outcome that affirms community and social space in contrast to detached and fearful public perceptions of amenities blocks. Lahznimmo’s breezy toilets and showers directly look to the sandstone cliff and open out to a communal circular wash basin which everyone shares, like a local well or watering hole. The adjoining café is elegantly a continuation of the structure and deconstructed to offer allow light in and views to the cliff through a window. Alan, café owner and local personality acts as an informal caretaker for the structure, park and amenities.

The sensitive and slight pavilions skirt the cliffs to maximise the open space of the park, improve movement patterns and encourage social interaction. Annabel Lahz (director) and Hugo Cottier (project architect) of lahznimmo architects emphasise that the outcome was the result of a long highly politicised process with a fiercely vocal local community that was opposed to change. But the long process offered several positive and surprising outcomes. The result is two minimal buildings that allow the dramatic topography to dominate. The materials of the structure reference the local environment while maintaining expressly modern geometries: timber battens are designed to weather like driftwood and precast concrete is coloured to match the sandstone cliffs.

The range of new architecture, for Sydney’s beaches, demonstrates a new cultural sophistication. Such experimentation with program and form suggests a different future for Bondi and Sydney’s beaches and a redefinition of Australian icons. Such cultural renewal is vital if local mythologies are to evolve into more ambitious and yet authentic realities.

Dr Scott Hawken

Urban Designer and Landscape Architect

Lecturer, Faculty of Built Environment,

University of NSW

FOOTNOTES

- Ford, Caroline M. 2014. Sydney Beaches: A History.New South Books.