table of contents

previous articles

next articles

Feature article

CONTENTS

A Century of Zoo Design

Taronga Zoo, one of Sydney’s signature leisure destinations, is celebrating its 100th birthday. Rachel Couper guides us through the architecture that has shaped the zoological park over the past century.

Taronga Zoo is a much-loved recreational attraction of Sydney. Positioned on Sydney Harbour with spectacular views of the city, the zoological park is an iconic cultural landmark. The architectural development of Taronga Zoo over the past 100 years charts a unique perspective on the zoological park’s evolution.

Originally the project of the NSW Zoological Society, Taronga Zoo was officially founded in 1916 after the Society relocated its Moore Park Zoo, which it had outgrown, to a larger site on the harbour. There were 228 mammals, 552 birds and 64 reptiles transferred from Moore Park to Taronga. The project made headlines, particularly the transfer of Jessie the elephant. Jessie was walked (alongside two circus elephants to keep her calm) from Moore Park through the city, to the harbour and then shipped to Taronga Zoo on a barge; finally, she was winched onto the steep site via a crane. Her journey captured the imagination of Sydney and ceremoniously marked the transition to the new zoo.

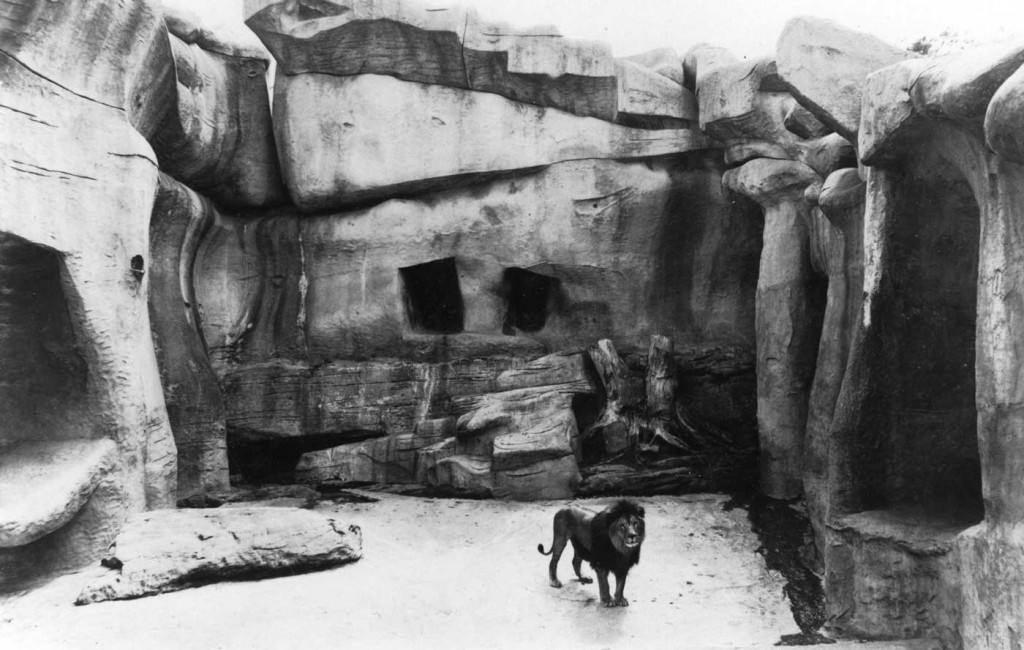

The founders of Taronga Zoo, particularly the Director Albert le Souef, had seen the steep grade and natural sandstone terraces of the new site as a fantastic opportunity to embrace a different style of animal exhibition. Originating from Hagenbeck’s Tierpark in Germany, the style utilised a system of hidden moats to create a theatrical display of bar-less enclosures, staggered across a manufactured terrain carefully constructed to resemble the natural environment. The design was revolutionary because it presented zoo-goers with a series of spectacular panoramas in which predator and prey appear to harmoniously inhabit the same scene. The architectural design became influential worldwide because it redefined the parameters of what constituted a culturally acceptable vision of animals in captivity. Seeing well fed, healthy specimens exhibited as if at liberty in outdoor, open-air enclosures was considered a vast improvement than the traditional vision of animals in cramped cages and barred enclosures.

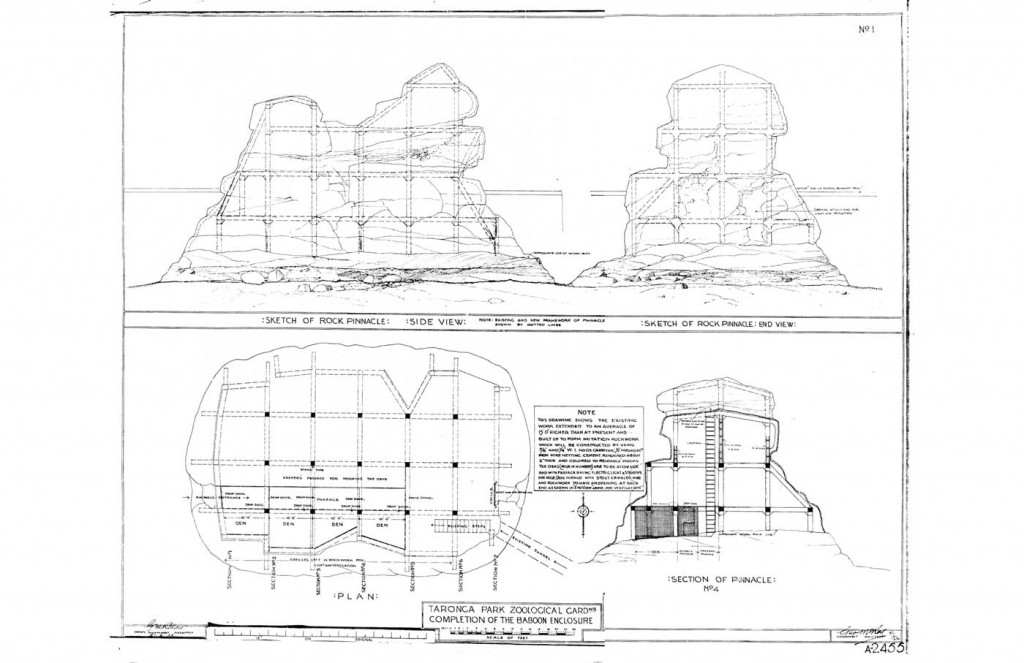

Taronga Zoo embraced these new design philosophies and the natural terrain leant itself to the installation of a series of open-air mock rock enclosures, nestled into the terraces. Mock rock was a method of construction that involved the application of ferro-cement over a sculpted arrangement of metal bars and galvanised mesh (chicken wire) create a rock-like appearance. It allowed the artificial terrain to blend somewhat into the existing landscape, creating the impression that the animals were exhibited in a natural setting.

By contrast, many of the buildings within Taronga Zoo were designed to stand out as architectural landmarks. The most recognizable, the main entrance, was designed in the elaborate Edwardian Baroque style with Beaux-Arts planning and featured a copper domed entranceway and ornate plaster decorations of flora and fauna. The Taronga Conservation Strategy suggests that the choice of this aesthetic spoke of: “the prevailing Zoo philosophy to amuse and entertain…”1. Much of the zoo’s early design (1913 – 1914) has been attributed to architect and army officer, Colonel Alfred Spain of Spain and Cosh. The Public Works Department continued what Spain had begun, and in 1915 established the upper and lower entrances, administration offices, Indian temple, bear and carnivore pits and aviaries.

Taronga Zoo had a strong emphasis on recreation and leisure during the early years and the grounds included a range of very popular picnic areas. Several small “hot water shops” supplied picnickers with pies and sandwiches, and were so called because they also filled billies for tea. The early zoo also had a large Federation Arts and Crafts style refreshment room that was famous for its freshly baked scones and bread rolls. By the 1930s amusements at Taronga Zoo included a bandstand for live orchestral performances, a miniature train track, a merry-go-round, swings, a sandpit, a kindergarten petting zoo, and a circus arena to showcase performing animals. Elephant rides around the zoo were still very popular at this time and daily events included two orangutans, Freda and Freddie, “enjoying” a tea party. Recreational features such as these were very much in keeping with international zoo practices at the time.

By the 1940s, however, several of the moats surrounding the open-air enclosures were filled in and mesh barriers installed instead in order to allow people to get closer to the animals. This departure from the Hagenbeck style signaled a change in the architectural philosophy of the zoo. When Sir Edward Hallstrom took the helm in 1941 the zoo’s focus shifted to hygiene and cleanliness and many of the enclosures were redesigned in stark concrete to make them easier to clean and to better protect the animals from the elements.

Though these designs were more practical, the overall character was very stark and sterile, which did not fare well in a 1966 review completed by Heini Hediger, an international expert in animal psychology. He made a swathe of recommendations for improvement, the most controversial of which was that no major zoo should be run by one person, particularly one without zoological qualifications. Though Hallstrom, who had generously invested a large amount of personal funds into the zoo during his twenty-six year tenure, found this assessment particularly confronting, many of the recommendations were eventually accepted and implemented by the Trust.

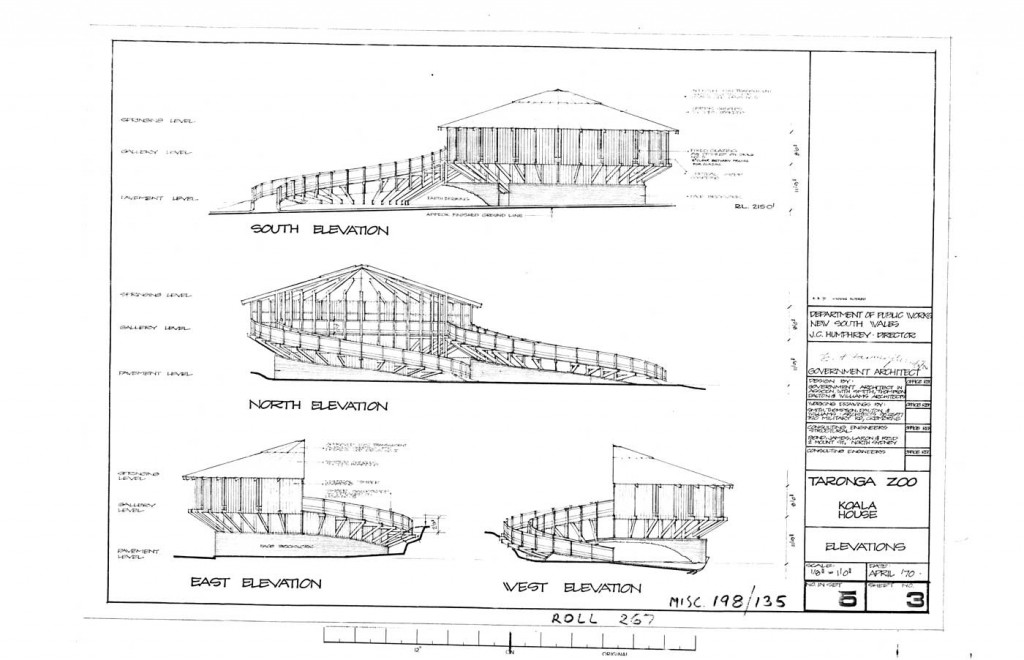

The review initiated a period of regeneration at Taronga Zoo and under the guidance of Ronald Strahan (zoo director from 1967 – 1974) the overall philosophy of the zoo shifted from recreation to education and animal conservation. In 1971 a masterplan was completed which bore the hallmarks of a Sydney School approach. The term “Sydney School” is used to identify a loose knit collection of local architects who celebrated the Australian landscape and aimed for an architecture that receded into the surrounding landscape. Those associated with it featured a common approach to form, siting, landscaping (with an emphasis on maintaining existing native vegetation), as well as materials which included clinker bricks and timber which was often left exposed in a rough-hewn or natural state.

Common to Sydney Regional style design was a response to place and the use of naturalistic landscape design with local Australian species in plantings. Its introduction at Taronga Zoo was an appropriate match for the program, allowing better and more prominent display of Australian native animals. The whole area was landscaped and several buildings constructed for native fauna during this period. The overall architectural philosophy was to provide close access to the animals without disturbing them. Two particularly iconic buildings of the period were the Rainforest Aviary and the Koala House by Public Works Department Project Architect Don Coleman. Opened in 1972, the Koala House was designed around a spiral ramp that encircled a cluster of trees housing the koalas, allowing visitors to view the residents from a variety of different heights. Lightweight in character, the hardwood timber structure features exposed trusses and a semi-circular shingled roof that covers the upper viewing platform. The Koala House was located to take advantage of an area of remnant bushland and further planting of native trees stitched the enclosure to its site.

This period marks a transition in which the Australian character and context of Taronga Zoo is celebrated and as the zoo matured, its prevailing philosophy expanded from recreation and leisure to include zoological research and education. Taronga Zoo championed a new zoo philosophy of animal welfare and wildlife conservation and a series of major capital works were undertaken throughout the zoo to bring it in line with international standards. The primary architectural approach embraced immersion design, in which animals are exhibited in geographic zones, in environments as closely representative of their native habitats as possible. Techniques utilised, such as in the altered lion and tiger enclosures, included glazing and lighting arrangements to allow visitors to get closer to the animals without disturbing them.

In 2004, BVN Architecture was commissioned to devise a new design for Taronga Zoo’s main upper entry including visitor arrival and parking facilities, as well as the heritage refurbishment of the upper entrance building and tram shed. New buildings that resulted from BVN Architecture’s commission include a shop, a café and a facilities building. The overall design took into account the sandstone plateau and the established fig trees, in addition to the historical tradition of the pavilion in a garden. In 2012, BVN Architecture was awarded the Institute’s Lloyd Rees Award for Urban Design for Taronga Zoo’s upper entry precinct.

Jackson Teece is responsible for a number of Taronga Zoo’s most contemporary projects. From 2006 – 2011 they designed and delivered the Wild Asia exhibit (2006); the male elephant holding facility and the Great Southern Oceans exhibit (2008); and the makeover of the chimpanzee exhibit (2011). The Great Southern Oceans is a 1.2-hectare exhibit featuring seals, sea lions, penguins and pelicans; the design incorporates the heritage feature of the former aquarium entrance.

In December 2013 Taronga Zoo opened the Lemur Forest Adventure, designed by Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects in collaboration with Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture. Located on the site of the former seal pools, the project includes a forest walk through, lemur walk through and night quarters.

Last year the NSW Government announced a ten year Centenary Master Plan for Taronga Zoo. This $150 million master plan includes projects, cofunded by Taronga and the government, to improve visitor experiences and create animal habitats. One of the first projects implemented as part of the master plan is the Sumatran Tiger Experience, designed by lahznimmo architects, an expansive new exhibit that will enhance Taronga Zoo’s breeding program for the critically endangered species will begin construction in February 2016.

The variety of architectural approaches adopted during the evolution of Taronga Zoo reflect the corresponding growth in zoo philosophies globally. The architectural design also mirrors changing attitudes to the Australian landscape and native animals, providing a unique reflection of the cultural development of Sydney.

Rachel Couper received a Byera Hadley scholarship from the NSW Architects’ Registration Board.

http://www.architects.nsw.gov.au/inform-public/byera-hadley-travelling-scholarships

Rachel Couper

Architecture Historian

FOOTNOTES

- Godden Mackay Logan, Taronga Zoo – Conservation Management Strategy, Sydney: Zoological Parks Board of New South Wales, 2002, 79.